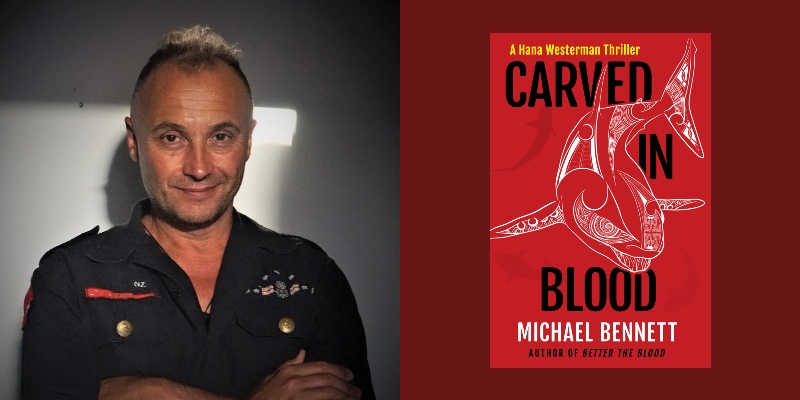

The Auckland City of CARVED IN BLOOD as seen through the eyes of Hana Westerman, the Māori ex-cop and former detective Hana Westerman, who serves the main character in Michael Bennett’s series. Photos courtesy of Michael Bennett.

Running the streets of this city, now, the hour before the sun rises, it’s a different place than it is the rest of the day. A different energy at 5am. I’ve run this same route through the empty roads of the central city every morning for years. I head down K Road, a mile-long strip which used to be Auckland’s sex-and-drugs marketplace; now it’s cafés and bars and hole-in-the-wall restaurants—less grim and seedy, more fun, but no shortage of raw edge. The place my daughter Addison loves more than anywhere on earth. The footpaths are all beautiful young humans Addison’s age, nose rings and tattoos so densely rendered that you think the owner is wearing an intricately patterned long sleeve shirt, not a singlet. But this time of the morning, there’s just the occasional cyclist, a couple of cars, and the dozen or so street dwellers who call K Road home, asleep on their beds of tarpaulin or cardboard.

Just them. And me.

Auckland is a decent sized city, a population the same as Philadelphia. But at this time of day the streets are empty, the shops closed, barely any cars. Just you alone in the world. You forget anyone else exists. You forget bad things ever happen.

Then I run around a corner. I don’t want to look, but I can’t help it. On the other side of the street, the liquor store. Police tape still across the front of the shop, a uniform police car out front.

I keep running. Needing to get to the waterfront, see the sunrise, leave the police tape behind. But no matter how hard I run down the steep slope of Queen Street, no matter how deep my heart rate goes into the red zone on my watch, there’s no running from what that police tape across the liquor store door means. Bad things do happen. Even in a piece of paradise like New Zealand. Bad things happen all the time. And a bad thing has happened to my family.

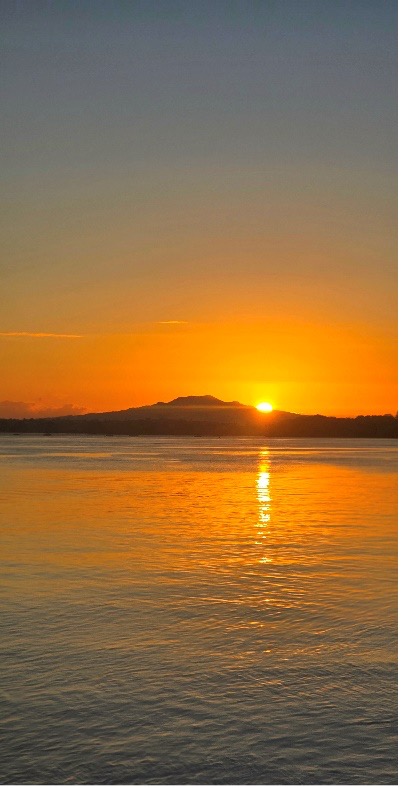

Down at the waterfront I push harder still. The sun is appearing above Rangitoto Island. Every morning down here plays out pretty much the same, with the sparkling waters facing east towards the great volcanic island that dominates the harbour. The clouds over Rangitoto go dark grapefruit pink at first. Then things happen real fast. It’s because of where we are in relation to the equator, I guess.

Pink gives way to another red-adjacent shade: a kind of dirty, rust-like bronze. In only a minute or two the transformation hits. The moment when everything changes, the rebirth, the world born anew. The rust shade lightens and explodes, a great layer of burning orange rises literally in moments filling the lowest band of the entire horizon. It’s breathtaking. Stunning. Like the pomegranate syrup layer being carefully poured into tequila sunrise glass. People spend their savings going to the Yukon to see the luminescent greens of the Northern Lights. Meanwhile, I lace up my running shoes every morning to watch a light show every bit as spectacular, just on the opposite end of the ROYGBIV spectrum.

I stop. I stare.

Another runner, approaching, slows and stops. She asks me if I’m okay. I haven’t even realized I’m crying. I say I’m fine. The runner knows I’m not. She squeezes my arm and carries on.

This morning, in my eyes the colours I’m watching aren’t grapefruit pink, the bronze of rust, the burning orange of pomegranate syrup. All I can see is what happened to my ex-husband, the father of my child, in that liquor store now with the police tape across the front. Jaye was looking for champagne to celebrate our daughter’s engagement. A man in a balaclava walked in and immediately started viciously beating the manager. Jaye intervened, the kind of dumb but brave thing Jaye always does, is always going to do. Cos that’s just who Jaye is.

Jaye intervened, rushing the guy with the only weapon at hand, the bottle of champagne he was considering buying. The guy in the balaclava turned the gun away from the manager, towards Jaye. The sawn-off barrel; the bronze shade of rust. He pulled the trigger twice. Two explosions. Two momentary flashes; burning orange. Then Jaye on the floor, a bullet in his chest, another puncturing his cheek and lodging in the side of his head. And his blood on the floor, mixing with the champagne from the bottle that smashed as he fell on the carpet. On the hard cold concrete, my ex-husband’s blood: grapefruit pink.

Rangitoto Island emerged from the depths of Auckland Harbour only six hundred years ago. It’s the newest volcano in a city surrounded by over fifty volcanoes, the first city built on a live volcanic field since Pompeii. Every morning when the sun rises, the sky fills with the vibrant shades of lava eruptions accompanying the rising of a new volcano, thrust up from the ocean floors; the colours of blood and fire and rust, the colours of birth and rebirth.

I’m watching a sunrise. But today, I’m not thinking of the world starting anew.

I’m thinking about the swelling in my ex-husband’s brain. Willing it to subside. I’m praying that, as Rangitoto Island thrust itself up from the darkness of the harbour floor, the fighter who Jaye is will find a way to push himself up from the shadows. That his body and his brain will heal. That he’ll come back.

I’m thinking about our daughter. I’m thinking of Addison, who needs her papa back.

And most of all, I’m thinking about the man in the balaclava. The man who took a gun with a rust-coloured barrel, who turned it on my ex-husband, who pulled the trigger twice, two burning orange flashes that sent small lumps of lead into Jaye’s body and his head. The man who then watched as Jaye’s blood mixed with the fizzing wine, turning the floor a dark pink. The man who snatched a handful of cash from the shop till and then stepped over Jaye’s body, and walked out the door.

As the sun fully reveals itself from behind the great volcanic island, as the shades of pink and rust and blood red retreat, replaced by a golden morning glow that makes everything seem achievable, everything seem possible to do and therefore absolutely necessary to do, as the dazzling glow fills my face, I close my eyes, and I speak quietly towards the burning celestial gases of the great star around which our planet orbits. Under my breath, I make a promise. To the sun. To our daughter. To me. To Jaye.

“I’m going to find the bastard that did this”.

***