Beginning in the 1990s, when he was 19 or so, Stéphane Breitwieser stole hundreds of artworks and antiquities from dozens of small museums, churches, castles and art shows in seven European countries. It’s a résumé that makes the 51-year-old Frenchman “perhaps the most successful and prolific art thief who has ever lived,” Michael Finkel writes in The Art Thief: A True Story of Love, Crime, and a Dangerous Obsession. With then-girlfriend Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus often serving as his “lookout”—she’d be ready to cough if a security guard approached while Breitwieser was, say, slipping a knight’s helmet into his backpack—“he averaged a theft every twelve days for seven years,” Finkel writes.

The combined value of this loot is a reported $1 billion, almost all of it lifted from exhibits with minimal security. A self-taught art aficionado, Breitwieser didn’t try to sell the artworks. Instead, he kept them in an attic bedroom at his mother’s place, where he shot home movies showing his haul. Breitwieser, arrested more than once, confessed to most of his crimes, and after serving relatively short sentences, he’s out of prison. Lest anyone think Finkel lionizes his subject, it’s worth noting that his book characterizes him as “a cancer” attacking the very idea on which museums are based—that art should be “accessible to all.” What happened to all the stuff he stole? It’s another wild tale, and though it’s now a matter of public record, I won’t spoil the ending here.

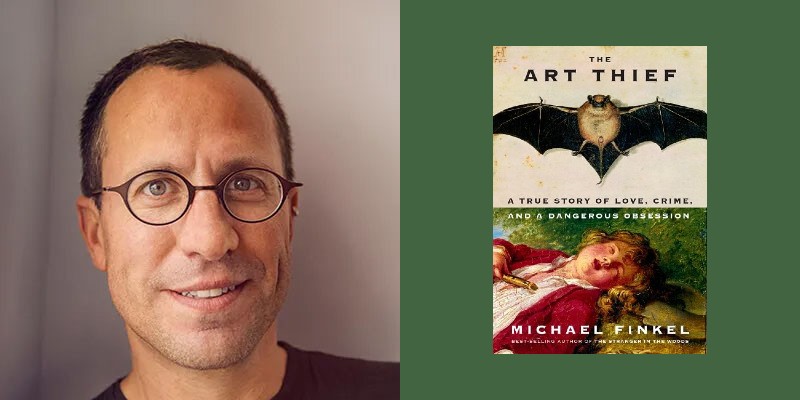

Finkel’s book arrives in stores 11 years after he first tried to land an interview with Breitwieser. The author—Jonah Hill played him in True Story, a film based on Finkel’s book of the same title—answered a few of my questions this month.

Kevin Canfield: You lived in France for a while, where Breitwieser did a lot of stealing. How did you first learn of his crimes?

Michael Finkel: I heard about Stéphane Breitwieser through French media, and there were three things that sparked my journalistic interest: The amount of museums and churches from which Breitwieser stole; the fact that he did it nonviolently, which sort of allows you to like the antihero; and I loved that he stole—at least it seemed from the outside—out of passion for art. What a great hook.

A French journalist friend of mine told me that this guy doesn’t speak to the media. I was like, Oh, game on! I have no real secrets about how to get someone to speak to me except for one, which is that I really like writing handwritten letters to people. I don’t really like to give that secret away because it’s so dang simple. But I think in this day and age, when everybody texts and sends email, to send a letter—and then just have patience—can work.

You’ve got patience. You initiated contact with him 11 years ago.

I didn’t even know this guy’s address, and I don’t like to creep people out even if I probably could have found his home address. I sent him a polite letter, written in French, through his publishing company (Breitwieser has published a memoir in France). It ended up taking months before he responded.

How did you then persuade him to agree to a bunch of interviews?

When I ask to interview someone, I feel like I give them a lot of power. I tell them pretty early in the process that if you don’t want to speak with me, I’m not going to write about you. I don’t have that skill set where I can report around something. I believe that John Carreyrou, the author of Bad Blood, a great nonfiction book about Theranos, did not get to speak to many of the principal characters, and did an amazing job of reporting around that. That’s not my skill set. I need to go right to the source. I really love to see what the person says, and then do tons of extra reporting. It makes everything richer.

He doesn’t really consider himself a thief. He’s someone whose tastes are on a higher level, and he’s a caretaker of these artworks—isn’t that how he sees it?

I think that’s a great way to read it. He’s not crazy. He knows that he’s stolen from museums and deserves to be punished. But truly, I think, right down to Stéphane Breitwieser’s core, he does not think of himself as a thief. An art thief is like the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, where (in 1990) thieves stuck a knife in a canvas to steal it. They don’t give a shit about art, they just want to exchange it for money.

I guess I’m a true crime writer. I wrote about a murderer (True Story). I wrote about a hermit who broke into many places (The Stranger in the Woods). And I like to hear people’s explanations and excuses for their crimes. Breitwieser truly felt that the art world is so full of shady characters that he convinced himself that he just had his own unusual acquisition style.

What was his first theft?

I think we can probably put the first museum theft when he worked as a guard when he was about 19—he celebrated his last day on the job by taking a 1,500-year-old belt buckle. The thing about his crimes is that he never felt guilt, he really never apologized in the 40-plus hours we spent together. He had all these excuses that seemed bullshitty to me and you—you know, most museums have storerooms filled with objects they don’t display, and he was really in his head thinking this belt buckle means nothing to 97 percent of the people who see it.

And then he falls in love with a woman named Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus. You saw home videos and CCTV footage that make it clear that she was deeply involved. One is a home movie of Breitwieser and Kleinklaus sitting in his attic and admiring all of these stolen items.

I totally understand that she didn’t want to speak with me. I tried my hardest, but I know it would’ve been a very weird situation for her to talk to a journalist, because she basically got away with it. The home videos were so fascinating, to see this woman who was a participant in a huge crime spree and then portrayed herself as a victim, which was a great move.

How did they work together? Artworks might be taken out in a backpack or her purse, they could be hidden in his clothes.

Maybe it was an extraordinarily fortuitous coupling. It’s that French expression – sangfroid, or cold blooded. I think the two of them were just able to do illegal things with a face of complete innocence. Her role, as Breitwieser repeatedly told me in our interviews, was greater than ever advertised. She was an essential part. They were really a team.

And a lot of times, it was simple as she’d stand in the threshold of a gallery and cough if someone approached while he was taking a knife to the silicone glue on a picture frame. You coined a phrase to describe this.

The silicone slice. His whole theory of crime goes so counter to movies and television. Eating in a museum restaurant, going on a guided tour—this idea that a thief would never do these things, he believes, is precisely what a thief should do. You can’t deny his physicality, his magician-ship, how he could pull off something under someone’s nose. And he truly loved the items that he stole.

That he actually loves the art he steals prolongs his career as a thief. If he chose to sell stuff, he’d expose himself to more risk.

The reason why museums get robbed is that the thieves aren’t thinking two steps ahead, they’re only thinking one step ahead: I can grab this thing that’s worth a million dollars. And then once you have it, what the hell do you do with it? You try and monetize it—that’s where you get caught. He’s smart enough to have known that.

But his love of art can’t have been the only reason for all of this, can it?

One of the things that Breitwieser kept insisting to me in the first couple of rounds of interviews was that it was not the thefts that thrilled him—that it was the treasure at the end of the theft. I disagree with that. He got some pleasure in pulling the wool over people’s eyes and subverting authority.

Maybe the most important point here is that, as you point out several times, there’s very little security at small museums.

Even amazing museums aren’t that well secured. And especially low-budget museums. There’s never that moment where the people running the museum are like, You know what, we should devote next year’s budget to better electric eyes for security and not buy any art. That’ll really make us money. And the whole point of a museum is to allow you to commune with art. I was very moved by the way curators spoke to me about this. As inelegant and imperfect as it may be, they really want you to feel as close to a painting as you can.

You begin one of your chapters by asking the question that underlies everything: “What is his problem?” So what’s the answer?

The answer I can give you without any psychological hat on is that he just fucking thinks the rules don’t apply to him! But just because you can get away with something doesn’t mean you should. We could all shoplift shit from the supermarket and get away with it, but we don’t because there has to be some way for society to function.