… it is not that I would forbid the making of statues, shaped in marble or bronze, but that as the human face, so is its copy, futile and perishing, while the form of the mind is eternal, to be expressed, not through the alien medium of art and its material, but severally by each man in the fashion of his own life. –Tacitus, from the Epilogue of Agricola

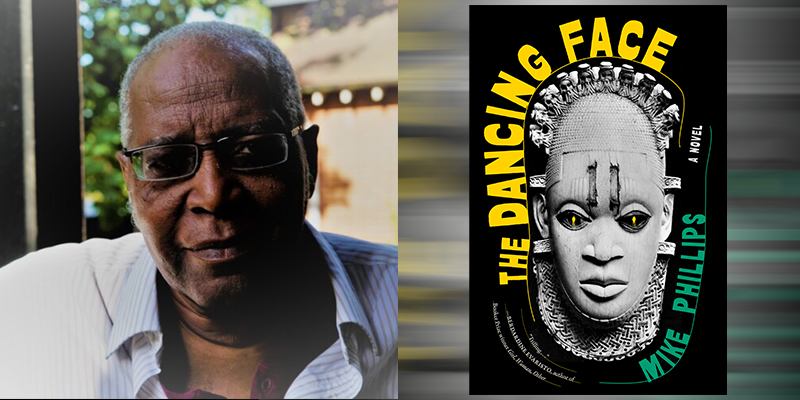

When I began, almost thirty years ago, to write The Dancing Face, I was resident writer at the Royal Festival Hall. I was faced, almost every day, with the inevitable question—what does a resident writer do? In my case, the answer was becoming a magnet for attracting others, and a central focus for a conversation about literature. All that meant was that I sat around for most of the day, in my little office at the top of the building, talking and talking about writing to anyone who turned up. As I remember, the book started in one of those conversations.

A rainy evening, sitting at a table overlooking the river with my friend Steve. Decades before this we had been fellow student activists, locked in intense arguments, marching, and bellowing, friends one day, enemies the next. Now he was a mild mannered accountant. He worked, he told me, for a fellow Nigerian, a millionaire in exile due to his political connections—an “evil bastard”, whose shipping firm transported goods throughout the Middle East. A couple of months ago one of Steve’s colleagues had made a mistake which meant that one of his ships had sailed in the wrong direction, been impounded, and detained in Egypt, at a cost of millions. The millionaire had been incandescent, and when he finally tracked down the culprit, he shouted, “If you had done this back in Africa I would have had you killed.”

The declaration stuck in my mind, partly because the way Steve talked about his boss was, in our circles, unusual, almost transgressive. Historically, my interest in West African art and artifacts had started with indignation at the fact of colonial theft, and this colored my explorations about identity, all of which had brought me to the issue of reparations.

At this point, it’s important to remember that, at the time, the detailed consequences of colonialism on Africans themselves were hardly an important part of the political language. International discussions of black struggles tended to start with items of news about racial conflict in Southern and Central Africa or the USA, and were inevitably framed within a liberal argument about equality. African identity and African differences tended to be ignored, subsumed within discussions about the meaning of racial and racist struggles. Talking with Steve about his boss was a revelation, and it struck me then that here was a facet about my own identity that I still had to understand and about which I had to write.

Another problem was the fact that I was already known as a crime fiction novelist. Even as late as the end of the nineties when The Dancing Face was published English audiences for the genre still tended to embrace the ‘cozy’ style of style of Agatha Christie, or the dashing postwar spy dramas of Ian Fleming’s Bond. My readers, by comparison, were “intellectuals”—campus radicals, and a small rump of black activists, who, all too often, were scanning the work for comparisons with writers like Salman Rushdie or Derek Walcott, or checking it out for quotes which might support one political point or the other.

The Dancing Face was, it seemed to me, a bit of a surprise for them. The book’s reception focussed, as I expected, on the action, while the role of the imagery had almost disappeared, serving for most readers as a sort of Deus ex Machina, which moved the plot forward.

Within a few years the novel had begun to recede in my memory, becoming simply one more story. And then, thirty years later, I received notice that it was about to be published, again, with a new cover which would aim it at American audiences. Surprise would be an understatement.

Purely by coincidence, the book was also being readied for broadcast as a TV series in Britain. Obviously something had changed over the last thirty years. That something was encapsulated in the new cover, which showed the face of an African statuette. This looks like a great cover picture, challenging, enigmatic, refocussing attention on the issue of reparations and the nature of West African identity.

Originally, when the book was published in 1997, my sense was that it was a boutique item celebrated by my more discerning readers. Something tells me now that this is about to change, partly because publication in America speaks to a very different clutch of interests and experiences.

The other part is about the way the world has changed in the last three decades. When I began writing the novel, no serious politician would have claimed the issue of reparations as part of his programme. All that changed with the political changes in Southern Africa, and now I can’t think of an internationally respected museum director or cultural envoy who would ignore the argument.

In much the same way the understanding represented by the statues of ancient Assyria, the Parthenon, and West Africa, among others, is now seen as a legitimate assertion of identity.

Looking now at the artwork on the cover of The Dancing Face, I am slightly puzzled about having gone nearly thirty years without opening the book. That’s going to change.

***