Nothing concentrates a story like the threat of an assassination.

If you’re a reader, you know from a glance at the flap copy that something big is going to happen in the book you’ve just picked up, something that will keep you turning pages right up until the moment when the assassin aims his weapon.

If you’re a writer, you know that you’re working in a genre that will give you plot velocity, a strong villain, and a big climax. You also know that you’ll always have a place to go, as long as you remember the advice of detective novelist Raymond Chandler: “When you run out of ideas, bring in a man with a gun.” Chandler meant it metaphorically, but an assassin fulfills the definition literally. An assassin is the ultimate “man with a gun.” He promises conflict on every page, and conflict means drama.

I found my latest “man with a gun” in a crowded movie theater.

I was watching Darkest Hour, the story of Churchill in the spring of 1940. Halfway through, Churchill calls FDR to ask for help. France is falling to the Nazis. The British are huddled on the beach at Dunkirk. But FDR can offer nothing. His hands are tied by American politics. As we cut to a long shot of Churchill slumped and despairing in a dark corner of his underground headquarters, I remembered that eighteen months later, Pearl Harbor would change everything. On December 22, 1941, Churchill would arrive in Washington. And on Christmas Eve, he and FDR would stand together on the South Portico of the White House to light the National Christmas Tree.

I thought, What a target they’d make! An assassin’s dream!

And just like that, I had the plot hook for my next novel, December ’41.

History tells us that in the first months of the war, the Secret Service worried bout the lone assassin or the small team operating in Washington. My novel tells us they were right to worry, because a German agent named Martin Browning has evaded an FBI dragnet in Los Angeles, and he’s coming to Washington, intent on making the fatal shots.

Now, successful assassins may change history, but I don’t believe that historical novelists ever should. So Martin Browning will try and fail. FDR and Churchill will survive to fulfill their destiny. The drama will derive from pursuit and evasion, from the assassin’s preparations and the pursuers’ investigation, from love affairs and double crosses, from close calls and shocking deaths, from the texture of the moment and the time, all of which can only be intensified by the threat of that “man with a gun.”

As I began to write December ’41, I considered the long line of assassination thrillers that preceded mine. Many of them followed the principles of historical storytelling that I embrace, which meant that while they might take license with the details of history, they remained faithful to the important facts and the big ideas, which mean that all of them revolved around an attempted assassination. I read a few for the first time, and I re-read a few to be inspired again. Here are seven that I consider top notch, in no particular order.

Day of the Jackal by Frederick Forsythe (1971)

The first classic among modern assassination thrillers. Disgruntled French military hire an anonymous English assassin, codenamed the Jackal, to kill de Gaulle. Soon the police begin to suspect that something is up. And the chase is on. Frederick Forsythe, a former journalist, writes in a semi-documentary style and does it so convincingly it reads like non-fiction. The prose is crisp and efficient, as cold as the killer at the heart of the novel. The structure is clean and unadorned. Forsythe puts his characters on the plot train, puts the train on a track that runs straight to the climax, and turns up the steam. And while it’s not a novel with a lot of twists or surprises, it’s rivetingly suspenseful. We know that de Gaulle survived several assassination attempts. But somehow Forsythe keeps us thinking that he may not survive this one.

Pursuit by James Stewart Thayer (1986)

I’m not the first novelist to think that our 32nd president would have made an inviting target for an enemy assassin. (And, as one of the characters points out in December ’41, an actual assassin fired three shots at him in Miami in 1932.) In this terrific page-turner, a German agent named Richard Monck escapes a POW camp in the state of Washington and begins his trek toward Roosevelt. Monk will stay a step ahead of the American authorities until the exciting climax on the presidential train carrying FDR toward Allamuchy, N.J., where his old lover, Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd, is waiting. From the opening line—“An order of toast would soon give him away”—to the thrilling climax, it’s a memorable ride that deserved a much wider audience. I read it thirty-six years ago and never forgot it.

The Eagle Has Landed by Jack Higgins (1975)

Yes, I know, that crack team of German Fallschirmjagers who parachute into the fictional English village of Studley Constable are not going to kill Churchill at his secret country retreat. Their plan is to kidnap him and spirit him back to Germany. Of course, complications ensue, and in the end assassination seems the only course. This was a huge bestseller and spawned a movie version starring Michael Caine as Steiner, the “good German” who leads the raid and must make the critical decision at the climax. All fictional, but Jack Higgins claimed he based Steiner on SS Colonel Otto Skorzeny’s spectacular raid to rescue Mussolini from imprisonment. There was a long string of World War II “men on a mission” adventures during this period, beginning with Alistair MacLeans’s The Guns of Navarone. Eagle is one of the best.

Three Hours in Paris by Cara Black (2021)

Instead of ending with the assassination attempt, Cara Black begins with the fateful shot. The target is Hitler. He’s standing in front of Sacre Coeur on the June Sunday morning in 1940 when he spent “three hours in Paris,” the only time he will ever visit the city. Of course, the shot misses, but it kicks this thriller into action. Hitler leaves Paris with orders to find the shooter, who turns out to be a woman named Kate Rees. She’s a prize-winning American markswoman who’s working with British intelligence. Or have the Brits been using her as a decoy? German security goes after her. The French underground attempts to help her while protecting their own. The suspense builds. Fresh and exciting, with a strong, resourceful, and relentless female as the main character.

The Man From St. Petersburg by Ken Follett (1982)

Ken Follett burst upon the world with his phenomenally successful World War II thriller, Eye of the Needle. Four years later, he turned to World War I for a novel about assassination. This time, Churchill isn’t the target. He’s the catalyst. As First Lord of the Admiralty, he enlists Lord Walden’s help in negotiating a naval treaty with Russian Prince Orlov, an old family friend and one of the Czar’s closest aides. But Orlov is the quarry of a Russian anarchist named Feliks, who wants to keep Russia out of the coming war and believes that killing Orlov is the way to do it. Follett is the master of this kind of material. He keeps ratcheting up the tension, even when the romantic complications stretch credulity, and we keep turning pages. Is Feliks successful? Churchill returns at the end, just to make sure that the world thinks not.

Night Work by David C. Taylor (2016)

So, how about Castro as a target? In April 1959, he visits New York City. And plenty of people want him dead, like the Mobsters who’ve lost their casinos, the Cubans who’ve lost their power, and the American businessmen who may lose control of their Cuban market. Three professionals are on their way from Miami to take care of their problem. The FBI and the CIA turn a blind eye. If Castro dies, their hands are clean. When Fidel gives a speech in Central Park, only New York cop Michael Cassidy stands between him and the assassins. David C. Taylor turned to novel writing after a career as a screenwriter, and he’s damn good at it. This one, the second in a series, builds to a slam-bang finale involving the assassination, $100,000 in stolen Mob money, cameos from Meyer Lansky and other marquee mobsters.

The Manchurian Candidate by Richard Condon (1959)

We began this eclectic list with a classic. Let’s finish with one. The plot is well known. American POWs, captured in Korea, brainwashed in China, sent home with psychological triggers cocked. One of them, “war hero” Raymond Shaw, has a domineering mother who’s actually a KGB agent and an ambitious father who wants to be president. Another POW, named Marco, pieces together what’s been happening to himself and others. Can he stop Shaw from an assassination that will change the course of American history? Even today, there are plot elements that feel ‘ripped from the headlines.’ And Condon’s prose, so different from Forsythe’s, has a velocity that matches the momentum of the story.

*

The book is always better, right? Generally, I agree. But the movie version of Day of the Jackal and the 1962 version of The Manchurian Candidate are classics, too. The ticking time-bomb thriller, especially when the bomb is a human being, is the kind of movie you simply can’t turn away from.

A few of the more memorable ‘attempted’ assassination thrillers I watched when I was writing December ’41:

The Tall Target, directed by Anthony Mann (1951)

Dick Powell plays a detective (eerily named John Kennedy) who’s riding on the train to Washington with President-elect Lincoln. There is an assassin aboard, and Kennedy means to stop him. A clever mingling of historical fact and speculation in this forgotten gem from a director who would become one of the best of his era.

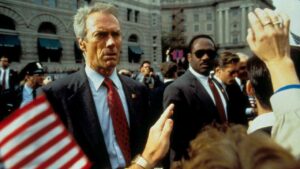

In the Line of Fire, directed by Wolfgang Petersen (1993)

Clint Eastwood as a Secret Service Agent who failed to save Kennedy in Dallas. John Malkovich as a psychotically efficient assassin. One of the best movies or either of them.

The Man Who Knew Too Much, directed by Alfred Hitchcock (1956)

There’s no better way to kick a story into gear than with a line like the one that a secret agent—about to die from the knife sticking out of his back—whispers to James Stewart: “A man, a statesman, is to be killed, assassinated… soon… very soon.” Now Stewart knows too much. And Alfred Hitchcock knew more than anyone.

***