Back in the 1990s there was a rise of young Black writers who got their start writing for so-called urban publications about hip-hop culture, rap and soul/R&B music as well as politics, community affairs and history. Labeled as “hip-hop writers,” these scribes came from various classes, academic achievements and family backgrounds. There were street dudes like Bonz Malone and Da Ghetto Communicator, Ivy League folks Skiz Fernando and Jon Shecter, hip-hop feminists Joan Morgan and Dream Hampton, Brooklyn boys Nelson George and Havelock Nelson, arty college dropouts Greg Tate and Barry Michael Cooper, HBC graduates Miles Marshall Lewis and Kenji Jasper, goofballs Sacha Jenkins and Elliott Wilson, politically charged Asha Bandele and Peter Noel, and, perhaps the most bourgeois member of the clique, a Boston born/elite prep school dude named Touré.

I believe we met either at public relations firm Set to Run or in the SoHo offices of The Source magazine, where Touré earned his first professional byline. Most of the writers lived in New York City, and we all knew one another and had various degrees of friendships. Touré and I were cool from jump, though our relationship never went further than small talk at parties and sharing a blunt while on the Jay-Z junket in the Bahamas in 1997.

Though Touré occasionally wrote for Vibe and XXL, most of his articles appeared in the big poppa of music magazines Rolling Stone, where he’d once been an intern. Ruffling a few feathers of other writers who were in disbelief that he leapt over them professionally and was documenting the culture with stories on Puffy and DMX, he just kept it moving.

Over the years I’ve heard some complain that he wasn’t street enough or thought he was stuck-up; in 1995 when he was covering the Tupac sexual assault trial for the Rolling Stone there were a few who thought he was down with the Feds. Of course, the latter wasn’t true, but none of that talk mattered to me, because the boy was a dope reporter and writer. He might’ve been a snobby prep school (Milton Academy) kid, but I actually preferred that than if he had pretended to be a “from the hood” b-boy.

For many of the Black writers during that era writing about “the culture” was just the beginning of a journey that led to screenwriting, various TV writer rooms, directing docs, non-fiction autobiographies and fiction, be it novels or short stories. Indeed, while a few of my contemporaries (Sister Souljah, Kenji Jasper) published novels, there were others exploring the medium of short stories to tell their tales.

Though it hasn’t been formally documented, an African-American short story revival began in the mid-1990s and bled over into the new millennium when various urban publications, including Ego Trip, The Source, Russell Simmons’s One World, Trace and Uptown, started publishing fiction. A few years later various anthologies were released with even more stories. A few that I read (and sometimes contributed to) were Gumbo (edited by Marita Golden and E. Lynn Harris), the Brown Sugar erotica series (edited by Carol Taylor), Dark Matter (edited by Sheree R. Thomas), Proverbs for the People (edited by Tracy Price-Thompson and TaRessa Stovall) and the short-lived literary magazine Bronx Biannual (edited by Miles Marshall Lewis).

Touré published the first fiction piece in The Source when “You Are Who You Kill: The Black Widow Story” appeared in 1999. Written in the style of a fake artist profile, Touré’s surreal narrative was a satire about the “keepin’ it real” rap generation who never smiled, was designer label, high fashion styled and ready to gun blast a sucker MC (“as in Melanin Challenged”) in a heartbeat. Even the girls were gangsta.

Carrying a pink Uzi at all times, the story’s anti-heroine Black Widow (who seemed to be modeled on Boss, Foxy Brown, Lil Kim and Mary J. Blige) wanted to start a race war, but not before her crew went shopping (and shoplifting) at the Gucci store. “I wrote ‘The Black Widow’ for The Source and had them publish it as though it was real,” Touré confessed in 2002. He was inspired by a 1985 Sports Illustrated story that George Plimpton wrote detailing the life of fictional rookie baseball player Sidd Finch.

“The challenge was to exploit all the personal and professional excess we know and love about hiphop (sic) while not pushing it so far that people would know right away that she was fake.” I think Touré underestimated the intelligence of The Source’s core audience, the majority who knew exactly what artists were signed to Def Jam Records, the label Black Widow was supposed to be on.

Nevertheless the story itself was a delirious romp through the ridiculousness of the rap record business, “The Game” as it was called in the 1990s. From the branding of “studio gangsters” who couldn’t bust a grape in a fruit fight to manufacturing fake revolutionaries who talked much soulful smack, but did nothing to the transformation of B-girls to “hoes.” While I enjoyed the story as it peeled back layers of hype and bullshit told to the reporter interviewing Black Widow while also shadowing her, the brutal ending put me in mind of the ultraviolent Natural Born Killers, my least favorite film of the 20th century.

I also admired the moxie of Touré, a respected music journalist, for goofing on the industry he worked with; however, like a few of us, Touré viewed himself as a writer documenting the industry instead of cozying up and claiming to be in “the music business.” I never got a chance to talk to Touré about his wacky short that was one part Mad magazine, one part Kurt Vonnegut, one part Greg Tate and one part De La Soul. With the exception of Ego Trip there wasn’t a lot of humor in hip-hop writing, but Touré had jokes.

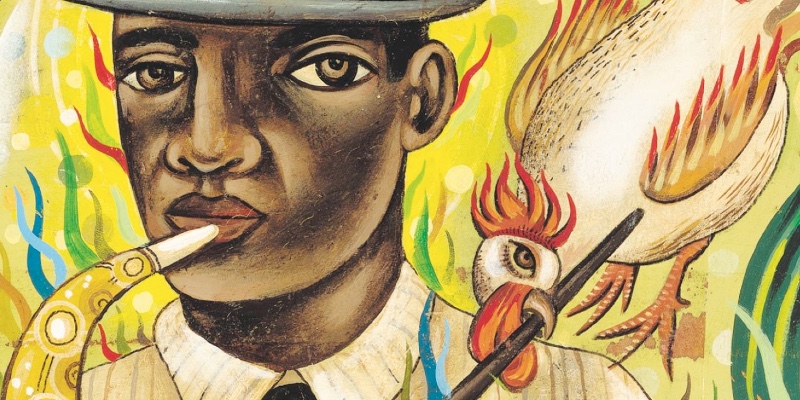

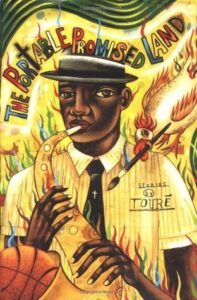

Three years after “Black Widow,” Touré released The Portable Promised Land, a collection of short stories that kept up the laughs while master-mixing in fables, Afro-Futurism, satire and magic realism. “The magic realism that I use in The Portable Promised Land…is a way of expressing blackness through my eyes,” Touré told writer Rebecca Carroll in 2004. “I see black people as so fresh and beautiful without even trying to be that I need a magic-tinged reality in my fiction to get all the beauty I see onto the page.”

While other writers were publishing stories grounded in reality, Touré’s book was delightfully bonkers speculative fiction that took its title from the first story he completed “The Sad, Sweet Story of Sugar Lips Shinehot, the Man with the Portable Promised Land”) in a writing class at Columbia University taught by respected novelist Stephen Koch.

Touré was brought over to Little, Brown and Company by publishing house by honcho Michael Pietsch, the man who discovered David Foster Wallace. “The Sad, Sweet Story of Sugar Lips Shinehot, the Man with the Portable Promised Land” was first published in the literary magazine Callaloo and tells the tale of a former saxophone genius in the be-bop 1940s named Sugar Lips (“…blowin til the paint cracked from the heat from his horn”) who can no longer play after being beaten lipless by some white Navy men.

Unable to blow his horn or kiss his woman, he was later given the power by a strange reverend to make white folks invisible, though he’s the only one who can’t see them. Of course that doesn’t stop him from being arrested and beaten at the police station, but, after laughing through the ordeal, Sugar was released, because the coppers thought he was crazy. While that story took place mostly in Harlem and others in Brooklyn, where Touré has lived since moving to NYC in the early 1990s, many of the pieces go down in a funky town known as Soul City where weirdness was ordinary and some citizens could fly while music was everywhere.

“Soul City was a place where God entered through the speakers and love was measured in decibels,” Touré wrote in the opening story “The Steviewondermobile.” Protagonist Huggy Bear Jackson, and his crew (Mojo, Boozoo and Groovy Lou) owned cool cars that only blasted Stevie songs as they rolled down the street. In that metropolis music was more than entertainment, it was also spiritual and religious.

In the “shout outs” section of the book Touré lays out his influences and inspirations, which included Zadie Smith, Prince and Basquiat; he also gave props to the brilliance of comedian Richard Pryor, who was one of the best storytellers of the 20th century. Though some believe that brother Pryor just pioneered cursing in comedy routines, but he was also a genius at weaving vivid ghetto narratives and observations about his daddy, winos, bad kids, upset women, talking monkeys and preachers; especially preachers.

While reading “A Hot Time at the Church of Kentucky Fried Souls and the Spectacular Final Sunday Sermon of the Right Revren Daddy Love,” a wild story about a rotund romancer rev who has slept with most of the women in his church, I thought about the preachers Pryor played on record as well as in the film Which Way is Up. Operating out of an abandoned KFC, Rev Daddy Love preached (his alter was the former chicken grease fryers) on the joys of sex as liberation, as Godly rather than sinful. After preaching a long sermon, he performed a trick that involved him taking flight.

All was well until trouble walked through the door knocked-up and pissed-off. As crazy and Blackadelic as “A Hot Time at the Church of Kentucky Fried Souls and the Spectacular Final Sunday Sermon of the Right Revren Daddy Love” was, I wasn’t surprised to learn that Touré’s classmates at Columbia panned the story so hard that brother man dropped out.

However, in a Hollywoodish turn of events Touré entered it in a short story contest sponsored by Zoetrope, a leading literary magazine owned by Francis Ford Coppola. In addition to flying Touré to Belize for the competition, his story won and was published in Zoetrope. I would’ve paid good money to hear the gripes of his former classmates when they heard that news.

Though expecting to read some autobiographical Boston boy stories (there is one, “How Babe Ruth Saved My Life,” but it’s far from typical), instead I was treated to texts that were more colorful than exploding skyrockets and as freakish as a gallery of Francis Bacon paintings. “The Portable Promised Land had a big impact on me,” says writer Ytasha Womack, author of Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture. “For one, I hadn’t read anything quite like it at the time, but it was part of a Black tradition of storytelling that I knew well. It was clear that he was trying to bridge traditions of the poets of the past with hip hop and the ironic edge of an Ishmael Reed for a turn of the century generation. It’s still one of my favorite books.”

The collection’s cast of kooky characters included Kojo Jenkins who made good money getting hit by cars (“Soul City Gazette Profile: Crash Jinkins, Last of the Chronic Crashees”), the prep school girl who has The Beatles song “Let It Be” blaring on the radio in her head (“They’re Playing My Song”) and a five-year-old kid named Nappy whose Black Panther parents wake-up to discover that overnight the boy turned into Little Black Sambo; the story is a soul kiss to Franz Kafka titled “The Sambomorphosis.” My personal favorite was “Solomon’s Big Day,” the tale of another five-year-old, but this boy has the power (or good luck) to fall into a Romare Bearden collage and get advice from a multicolored man on the secret to becoming a great artist.

“You must give your paintings your way of seeing. Don’t tell it as it is. Tell it as it is for you and you alone.” The following day the kid displays his gifts painting in class with intensity as he fell into a trace. “He was so alone he could hear nothing but his brush meeting the paper,” Touré wrote. This is the loosest story in the book as it steps away from James Brown “the one” and boards Clinton’s mothership wearing Bootzilla glasses.

With The Portable Promised Land, Touré pioneered a kind of hip-hop fiction that wasn’t about rappers, gangstas, hot women, baby mommas, corner boys or b-boy millionaires; this wasn’t The Coldest Winter Ever or about being True to Game or those sexually raw freaky folks in Zane’s books. This was an update to the free jazz fiction of Amiri Baraka and Ishmael Reed. Touré was doing tricks with language, casting spells with bizarre plots while also sampling brand names, various music and television shows, then sprinkling them throughout a couple of lists (“We Words: My Favorite Things,” “A Guest!”) and stories.

These were the kind of stories generated by a love of pop culture and Black folks as well as blunted sessions listening to A Tribe Called Quest, Outkast and Kool Keith, the soul of D’Angelo, Erykah Badu and Macey Gray, the brutal beats of DJ Premier, Dr. Dre and Tricky. “Touré was writing in the tradition of Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo or Henry Dumas’ Ark of the Bones,” Womack says. “Amiri Baraka described Dumas writing as Afrosurreal, a term later adopted by Bay Area poet D. Scott Miller to describe the mixture of hyper realism and the fabulous that kept popping up in the creations of Africans in the Americas.”

Looking through the shout-outs in The Portable Promised Land there were a few omissions I believe should’ve been on the list including Warner Brothers cartoons (& Ralph Bakshi’s bugged out flick Coonskin), Pedro Bell and Roger Dean album covers, Jack Kirby drawn Marvel Comics and the blistering racial satire Negrophobia by Darius James. Between reading Ralph Ellison and Vladimir Nabokov, I think Touré must’ve also been sneaking peeks of Iceberg Slim and Donald Goines’ ghetto novels as well as midnight screenings of Blax-cinema classics The Mack and Darktown Strutters.

“Honestly, at the time I read Touré’s work, I hadn’t read Baraka or Dumas,” Womack says, “but I had read Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison and Song of Solomon and other works by Toni Morrison. Both had a lot of magical realism and were heavy stories. However, Touré’s work had a great bit of humor and satire. He reminded me of black folktales like the Signifying Monkey, Ananse, or John Henry but he was telling fantastic versions of tales that reflected the times.”

Two years after The Portable Promised Land, Touré published the novel Soul City (which featured blubs from white suit wearing Tom Wolfe and former Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown, the two most un-soulful people on the planet) a return to the same funky, mystical landscape. Why he choose to make another journey to the same place I don’t know, but that visit wasn’t as enjoyable as the previous one.

Though Touré more than likely thought of himself as a literary writer, he wrote two volumes of genre fiction and published them at a time when readers just weren’t ready. In 2020, while interviewing British novelist Zadie Smith on The Touré Show, he disowned Soul City claiming it was something “which no one should read.” Author Ytasha Womack, whose latest book The Afrofuturist Evolution was published in March, doesn’t agree. “Soul City is ethereal and yet very real, like a world within a world, or how one sees the world around them. But everyone can’t see it.”

Touré, who today appears on various news programs and does strange Tik-Tock videos about the Diddy trial, has seemingly stepped away from writing fiction completely. In 2008 he told website Fanzine that he was working on two novels, but so far nothing has been published. He might still be writing fiction, stashing the pages Emily Dickinson style, but there hasn’t been any new tall tales since Soul City.

All the same, I believe that both The Portable Promised Land and Soul City were ahead of their time, coming years before there was much interest in Afrofuturism, Afrosurrealism, TV shows Atlanta, Random Acts of Flyness and Lovecraft Country, the films of Jordan Peele, Boots Riley and Ryan Coogler, the stories of Tananarive Due, Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah and Sheree Renée Thomas, the novels of Victor LaValle, Nnedi Okorafor and Marlon James, the graphic novels of Tim Fielder, John Jennings and Sanford Greene, the music of Janelle Monae, Adrian Younge and Meshell Ndegeocello, the sci-fi scholarship of Lynell George, Nisi Shawl and Reynaldo Anderson.

In other words, now that there exists more of an audience for Afro mothership weirdness in the arts, Touré’s madcap mojo metropolis should also be on the literary menu. The Black speculative fiction road has been well travelled; hopefully it will also lead back to the future shocked, wild styled prose of The Portable Promised Land and Soul City.