We humans love to make up stories about our lives—things we encounter, things we struggle to understand, things that amaze or frighten us. Oral and written storytelling is a key part of our history and existence. Some of the stories are truthful while others are not, though the creator might not have known it at the time.

These stories give us myths, legends, and superstitions, tales often born out of misunderstood mysteries or perceived dangers that may or may not be real. Over time these narratives can gain a life of their own as they are passed down to neighbors, family, and friends, and then spread through communities.

Most (though not all) monsters are mythical creations, and the very word “monster” summons to mind something hideous, scary, and dangerous. Throughout history, humans witnessing frightening natural phenomena they didn’t understand created monster narratives to explain their experiences.

Earthquakes in Japan were believed to be caused by a giant catfish named Namazu. A downed ship on an angry sea was blamed on a sea monster called the Kraken. An Iroquois witch with a whirling form was thought to cause tornados. And a Greek monster trapped beneath Mount Etna caused volcanic eruptions whenever it tried to escape.

Anthropomorphizing and lending humanlike emotions to these uncontrollable natural events makes them feel more predictable. This lessens our sense of helplessness while also giving these events a monstrous façade that represents the danger they impose.

These myths and monsters may seem silly to us today, yet we tend to cling to these stories and retell them even after we know they’re nonsense. Why? Well, for one, they are entertaining and make for fun mystery fiction. But they also serve a broader societal need by providing warnings and examples we can use to teach others. They can make sense of a senseless world when things go wrong, or define beauty and magnificence that may be beyond our comprehension.

Religions, both ancient and modern, are essentially myth-based. The various gods and the stories that go with them are attempts to teach, atone, and explain behaviors that are horrifying and cruel, or that demand justice.

And religions have their corner on the monster market to aid in this objective. Consider Christianity’s Devil, or Judaism’s Golem, or the Jinn of Islam. The parables these monsters come wrapped in often serve as a handbook for community standards and acceptable behaviors, providing guidance and rules to live by.

Some monsters come with moral lessons outside of religious doctrine. Godzilla teaches us what can happen if we mess around with nuclear bombs. Frankenstein’s monster is a misunderstood creature and a victim of his creator’s hubris. Medusa’s fate serves as a warning about the risks of betrayal, jealousy, and pride. And monsters like vampires and werewolves often represent our fear of losing control and giving in to our darker thoughts and instincts.

Regardless of the type of monster, there is one thing they all have in common: fear. Monsters put a face to our deepest terrors. Even stories that feature them as gentle, misunderstood creatures typically have some degree of fear at their base. We’re afraid of the way they look, their size, their behavior, or what they represent. We’re afraid of being helpless, hurt, or killed. We’re painfully aware that the monsters could come for us at any time.

Yet we’re drawn to them, not just intrigued but often morbidly fascinated. Even real monsters, like a serial or spree killer, tend to capture and keep the attention of a large segment of the public.

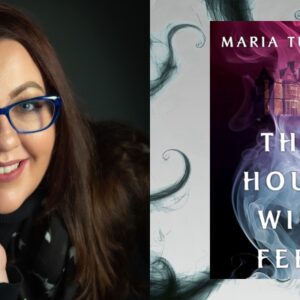

Of course, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention cryptids, the “monsters” the protagonist in my Monster Hunter Mysteries seeks out. Tales of creatures like Nessie, Yeti, Chupacabra, the Jersey Devil, and many more have been around for centuries. Perhaps they’re figments of someone’s imagination, or a story made up to get attention or entertain. Maybe they’re the result of an optical illusion or someone’s idea of a prank. Then again, maybe some of them are real.

We no longer believe monsters trapped in volcanos cause eruptions, so why does belief in cryptids, or any monster, persist? In this age of modern science and a well-explored world, it may simply be because we humans still need a little mystery and magic in our lives.

That’s the motivation behind Morgan Carter, the cryptozoologist in my books. She is smart, educated, logical, and a skeptic. She can’t believe any cryptid exists without solid proof, but she believes in the possibility of them, a philosophy her mother—also a cryptid hunter—coined as plausible existability.

While the world grows smaller every day, media influences help perpetuate the myths. Books and movies build on our fears by creating bigger and better monsters, and we eat it up.

It turns out fear isn’t all bad. Studies have shown how those goosebumps down your spine or the gallop of your heart can be good for you. And because so many of today’s monsters live in the pages of books or on the big screen, it allows us to experience fear in a safe, controlled environment.

Amusement parks with thrill rides like rollercoasters, and haunted houses at Halloween do the same. The screaming and emotional intensity are cathartic, and they trigger the release of adrenaline, which in turn helps us think better, act faster, and develop the instincts all creatures need to survive. Fear also triggers the release of dopamine, which in turn improves our moods by creating a chemical high.

It helps explain the existence of adrenaline junkies who frequently engage in high-risk activities or gravitate toward intense occupations. Fear can even be fun, so much so that there’s a lab in Denmark dedicated to studying it.

But like most things in life, too much can be harmful. Chronic exposure to fear or stress, particularly when the threats are real, can lead to things like PTSD, social anxiety, and chronic illness.

Thousands of years ago, a caveman witnessing a total eclipse of the sun undoubtedly came up with a story to explain what he saw in terms he understood. Doing so would have made it less frightening to him, and when the story was then passed on, it might have made future eclipses seem less scary to others.

We can make fun of said caveman, but we, too, are prone to myth making as we struggle to explain things we don’t fully understand, like the Great Pyramids, the lines of Nazca, or black holes in space. We develop stories by using what we know to try and explain what we don’t.

One thousand years from now, future humans may well be laughing at our naïveté just as we laugh at the caveman’s. Assuming, of course, that some alien monsters from space haven’t wiped out our existence by then.

Ah, did that trigger a little chill down your spine? You’re welcome!

***