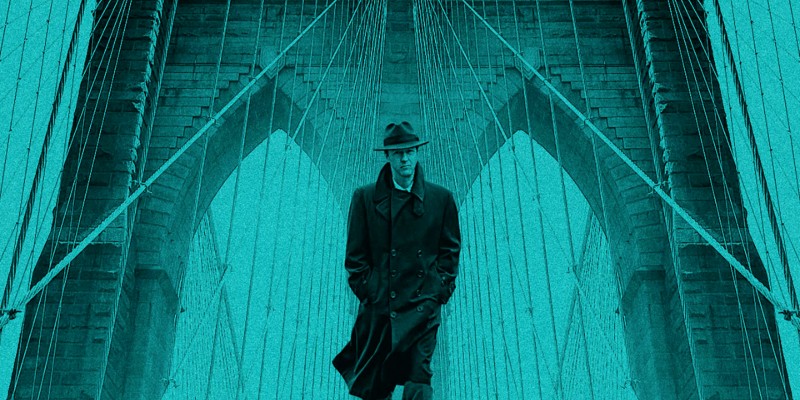

The first thing you’ll notice about Edward Norton’s Motherless Brooklyn adaptation is probably the thing you’ve heard the most about it so far: that it’s set forty years earlier than the novel from which it takes its name, in the mid-50s rather than the mid-90s. Norton, who spent nearly twenty years adapting Jonathan Lethem’s classic book, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction when it was released in 1999, has turned it into a perennial noir story: a narrative that might as well be from the end of the era of literary Modernism, rather than distantly aflame with postmodernism. Motherless Brooklyn the novel is a referential, thoroughly interior affair—rather like its protagonist, Lionel Essrog, a thoughtful PI henchman with Tourette’s Syndrome, it has digested decades of communicative broadcasting and is constantly processing them, spitting them out when the timing feels right. With all its chiaroscuro and detectivey melancholy, Motherless Brooklyn the movie might as well be the content that the novel has already taken in and chomped into vernacular. Lionel knows who Philip Marlowe is; he quotes from him randomly when he thinks about how he, too, is a detective. And “When I heard ‘Alfred Hitchcock,’” explains Lionel in the book, of his ‘Tourette’s brain,’ “I silently replied ‘Altered Houseclock’ or ‘Ilford Hotchkiss.’” The point of the novel Motherless Brooklyn is that it’s not noir—it just holds on to some of its syllables.

So why make the movie noir, then? Well, the other thing you’ve probably heard about Motherless Brooklyn the movie is that it features an entirely new plot (in addition to hitting the novel’s key moments, which means the film topples at two and a half hours long). This plot, very-Chinatown, involves a crooked power-hungry urban-planning puppetmaster named Moses Randolph (Alec Baldwin) who has a plan to annihilate minority community spaces in New York City. Moses Randolph is a symbolic alloy of a villain, mostly built out of Robert Moses but nodding a little bit to Fred Trump and bearing the occasional jingoistic slogan a la Donald Trump and sounding at one point, honestly, a little bit like Harvey Weinstein. He’s a monster, an almost mythological evil—a racist, patriarchal griffin or other medieval mammalian composite built out of others’ most dangerous parts—whose deep, multifaceted, and on-the-nose villainy might have felt hyperbolic before 2016 and now, sadly, just feels quotidian. Characters like Moses Randolph make noir feel so futile—they make noir what it is. Powerful bad guys emphasize timeless pointlessness and Sisyphean battles against corruption, discrimination, and extermination. And so, the noir movie Motherless Brooklyn is ambitious and earnest and surprisingly contemporary for all its insisting on returning to an earlier time. But the film has its mouth full of all these noir-ish things, and this means that it barely has room for its main character, Lionel, which is a shame, because Lionel is the best part.

* * *

Edward Norton plays Lionel in the film (in addition to writing and directing it) and he’s great, though he’s clearly styled the character on Dustin Hoffman in Rain Man and this is fairly unproductive. Still, Lionel is weary, and no one can look weary so well as Edward Norton. The most widespread criticism of Motherless Brooklyn the movie, so far, is that Lionel’s disability feels like an add-on, a means to (sympathetically) cut down a traditional tough-guy noir protagonist, a way to make the overall sense of pain feel more painful, the fruitlessness feel a lot more fruitless, and the noir feel a lot more like noir. It’s unproductive to gauge the worth of an adaptation by its fidelity to its source text, but it’s also hard to watch Motherless Brooklyn without missing the book’s Lionel. But the reading that Motherless Brooklyn the movie completes of Motherless Brooklyn the book, which insists on finding, and then making, noir where there’s very little of it, also illuminates the unique ways that the book inhabits a detective story framework.

The central mystery in Lethem’s novel is not the whodunit that starts both iterations—the meeting-gone-wrong that leaves Lionel’s beloved mentor, the petty gangster-and-private-detective Frank Minna, dead and poses lot of questions about how and why. Lethem’s novel, which takes place mostly in Lionel’s head, pounds with vibrant explorations of language—of words and patterns and sounds and the feelings that they produce. Lionel, a man of outbursts who has had Tourette’s since childhood (a bored, boring childhood at Brooklyn’s St. Vincent’s School for Boys), spends the novel making connections. His obsessive tics, which often rhyme, repeat, and anagrammatize, are clever and energetic in their extremes, as he seeks to match the sounds of words to the feelings he needs to fill. In his thoughts and speech, he explores consonance, assonance, alliteration, anaphora, onomatopoeia, meter, synesthesia, and even apostrophe. He plays with language—the English language. What is Lionel, except a poet—except, in a Greek tragic sense, a poet with a catch? Like Cassandra, the prophetess cursed by the perpetual disbelief of others, Lionel has the gift of poetry in such a high dose that he has to fight to talk in prose. “Water, water, everywhere, and not a drop to drink.”

His name is ‘Lionel Essrog,’, but he calls himself different things: “Liable Gusscog. Final Escrow. Ironic Pissclam. And so on. He explains, “My own name was the original verbal taffy…”

His name is ‘Lionel Essrog,’, but he calls himself different things: “Liable Gusscog. Final Escrow. Ironic Pissclam. And so on. He explains, “My own name was the original verbal taffy, by now stretched to filament-thin threads that lay all over the floor of my echo-chamber skull. Slack, the flavor all chewed out of it.” The tics lift momentarily once he has satisfied the feelings that he needs to produce by saying and thinking things. But aside from this knowledge, his Tourette’s is a yanking, yearning mystery to him. And the (familiar) mysteriousness of his own mind makes social communication, if not a mystery, than a mire. In flashbacks, he tells stories about being a slave to his impulses—for example, getting beaten up in school for having the urge to kiss everyone and not being able to control it. He tries to figure out a way to explain it, eventually settling on the panicked summation “it’s a game!” This barely saves his skin.

The story features frequent bursts of flashbacks, of memories. There are lots of repeated details in Lionel’s recounting, and for the reader, through this all—connections are made and satisfying explanations are provided. A flashback is a kind of a tic of the novel, Lethem’s book suggests in a way—a regurgitated articulation that manifests to satiate a yearning, a sensation. He is at home in the novel form (where, like the mind, thoughts have infinite breathing space) more than he is in speech. In the novel form, we see how ordinary communication is inadequate to Lionel’s abilities and needs—someone who can only express himself in cubism in a world of landscapes and still-life.

Lionel’s inability to fully participate in social interactions leaves him an outsider, generally. Even those who know him well—Tony, Gilbert, and Danny, other former students at St. Vincent’s who also come to work for Frank Minna—can’t quite understand him, although they are used to him. Gilbert and Lionel are the backup crew for the meeting Frank goes on that goes awry and leads to his death. And Lionel, guilty and missing the one person who has totally chosen his company, attempts to solve the murder. It’s not as grandiose as in the movie, but it’s not tiny, either—it involves a Zen Buddhist front and a Japanese corporation. But it does not consume the story; Lionel consumes the story. And the story only becomes a mystery because Lionel insists on making it one.

* * *

Lionel, who already works in a semi-private-investigator capacity anyway, is very well-versed in genre. Language and communication are also the central mysteries in Motherless Brooklyn, and in all these ways, “mystery” is kind of the genre in which he lives. “Mystery” is how he expresses himself, how he exists in the world. Once his mentor is gone, Lionel turns his absence into another mystery—another bothersome unanswerable, unclassifiable tic. Another riddle of pacing and time needing to be picked apart. Another unsatisfying detail needing to be fulfilled. Indeed, Lionel’s tics manifest from the need to make connections between things. So, too, does he turn his life into a mystery to make a connection: his biggest connection, a way to fulfill the death of the one person he ever felt connected to.

Once his mentor is gone, Lionel turns his absence into another mystery—another bothersome unanswerable, unclassifiable tic.

Connections, in the novel, sometimes manifest as inside jokes—as Minna bleeds out in Lionel’s arms in the back of their car on the way to the hospital, he begs Lionel to tell old-stock “guy walks into a bar” shtick, with the understanding being that Lionel won’t be able to finish the gambit without blurting the punchline in the middle a few times. Minna’s display of great familiarity with how Lionel works is the greatest demonstration of understanding in the novel. The two are able to communicate volumes precisely because they can both decode Lionel’s particular orthodoxies.

It’s been suggested by critics that the movie Motherless Brooklyn’s lack of a cogent way to represent Lionel’s complex interiority and thought (cinema’s eternal hurdle, anyway) is its biggest failing. Maybe. Maybe it just takes on too many social problems at once and tries to condemn them with the same tremendous force. Simply, maybe it tries to say too much. But a different way to look at this problem is to remember how the novel Motherless Brooklyn achieves a celebration of expression—how it pursues its particular demons by speaking in tongues (as it were) rather than so squarely, clearly condemning them. Through all its themes of excess, the novel Motherless Brooklyn is about choosing the right words. Lionel filters through guff to get to the perfect sounds. He and his imperfect thoughts elevate the story from being a familiar revenge-tragedy neo-noir plot to a meaningful exploration of personal and interpersonal understandings—a mystery about the words we use, and what we need them to say.