Dwayne Robinson was murdered in 2011. Walter Gibbs escapes into South American exile after being accused of multiple #MeToo crimes in 2020. Neither of them was real, but that doesn’t mean these events were trivial to me. The music critic Robinson (stabbed to death in my 2011 novel The Plot Against Hip Hop) and the entertainment hustler Gibbs (called to task in my just-released novel The Darkest Hearts) were created in my first novel, a love story called Urban Romance back in 1993, and have appeared in my fiction ever since. That first novel, which dealt with both young love and the beginnings of hip hop, was inspired by my stint as a music trade reporter from 1981 to 1989. I spent most of those eight years attending concerts, interviewing musicians and industry executives, and getting a keen insight into a lucrative and cynical business.

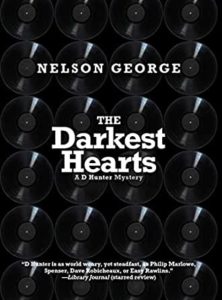

I wrote five novels between 1993 and 2003 and with each book, music history, often funneled through the characters of Robinson and Gibbs, was key to the narrative. It’s a world that happens mostly at night in recording studios and nightclubs. It’s a world filled with money, glamour, sex and drugs. Because of these elements my novels became increasingly dark in tone and infested with crime. By the time I wrote Night Work in 2003 I knew I needed to dive deeper into noir, pushing love to the side, instead filling the stories with greedy dreams of success and money. Robinson and Gibbs are in Night Work, but the most important leap I made into noir was introducing D Hunter, a brooding bodyguard who wore all black and had a closet full of demons. I’d always loved the work of Chandler and Hammett. I saw the film Chinatown in a Times Square theater. Later I discovered Chester Himes’s Coffin Ed & Grave Digger Jones crime series. Walter Mosely’s Easy Rawlins books, particularly Devil in a Blue Dress, encouraged me to venture deeper into noir. When I wrote The Accidental Hunter in 2004, I made D Hunter the central character and based him heavily on the huge, anonymous men who guard club doors, VIP sections, and pop stars. I remember seeing a picture in a tabloid of Britney Spears exiting a car with the body of a big African-American just out of the frame, and knew that’s who D Hunter was. I thought of The Bodyguard and wondered if I could flip that tale, so that the heroic bodyguard was black and the endangered singer was white.

With each book, music history…was key to the narrative. It’s a world that happens mostly at night in recording studios and nightclubs. It’s a world filled with money, glamour, sex and drugs.Since I already had a backstory established for Robinson and Gibbs, I kept them around. Their careers intersected with the younger D Hunter, who they either mentor or hire in my literary universe. Moreover, the long history of black music America gave the novels that followed narrative drive as the titles suggest: The Plot Against Hip Hop, The Lost Treasures of R&B, To Funk & Die in LA. With each novel the cast of intertwined music biz characters has grown, their fortunes rising and falling with the music biz. Gibbs started by managing R&B singers, shifted to hip hop and, by The Darkest Hearts, is in various entertainment-related online ventures. Night, who was a young neo-soul singer and sometime gigolo way back in Night Work, is now a fallen star and recovering coke addict, who’s hoping a turn towards political songs will revive his career. Most importantly, D Hunter has grown from a big intimidating black man in post-9/11 New York to a polished talent manager in sunny pre-COVID-19 Los Angeles. The events of the previous D Hunter books have shaped his present and haunt his future. In fact the death of Dwayne Robinson a few books ago still helps shape D Hunter’s world.

The Darkest Hearts contains a book within a book. Slipped in throughout the new novel are selections from an unpublished 2011 manuscript called The Plot Against Hip Hop by Dwayne Robinson. The Plot Against Hip Hop is also the title of the novel in which Robinson’s murder triggers the action. In that book only a few brief selections appear. In The Darkest Hearts, the unpublished nonfiction book is quoted liberally and is crucial to the story, making The Darkest Hearts a bit of a sequel to The Plot Against Hip Hop while containing sections of the unpublished nonfiction of the same title book. You got that? LOL.

In various excerpts the late Robinson goes on several long rants about the state of hip hop and its relationship to capitalism and race. Here he speaks from beyond the grave:

The dance between creativity and commerce for black artists in America is always fraught since the very gifts that liberate the soul are easily commodified into simple formulas that diminish the spirit, transforming deep passion into disposable product. Hip hop has manifested in so many creators an embrace of a limited, essentialist menu of stories and emotions that narrowed the MC and their audience’s humanity. To be a thug or a gangsta bitch or a backpack MC was to be a mythological persona crafted to be easily understood and marketed, fitting into expectations of black life in a nation for whom stereotypes are reality.

Why think about the complexity of any individual life when through the right clothes, slang and graphics you can telegraph your message—no need to think. Just enjoy your synthetic black experience and kick back with a cold brew or a blunt.

So the D Hunter music noir universe has been reverse-engineered. I started writing a very different kind of fiction, but my source material took me on a journey where my journalistic background, the music I love, and my affection for crime stories have guided me. As with many memorable journeys, I didn’t know exactly where I was going or how I was gonna get there. Then the destination spoke itself into existence. I followed the path and I am now quite pleased with where I’m standing.

***