Part One: An Unkindness of Ravens

It was almost three years to the day after the great quake had laid waste to so much of San Francisco’s pride that the first of the extortion letters arrived, dated April 21, 1909. This one appeared at the door of the home of Mr. James O’Brien Gunn, president of the Mechanics’ Savings Bank in San Francisco. Like the other two which followed it on April 26, the missive was menacingly signed “The Ravens.”

“Dear sir,” it began:

Read this letter well and weigh each word of it to its full weight, for they mean exactly what they say. We wish to tell you that on next Friday night, April 23d, you must be in front of the Van Ness Theater with $3000 dollars to deliver us in cash, if you wish to ensure the safety of those that are dear to you…. Our plans are well laid and will be performed to the letter if you do not accept our request.

We do not shoot or stab, but we handle a Hindoo poison which is known by the East Indian to be the quickest and deadliest poison that can be concocted from plants of poisoned juice, a poison that knows no antidote, for it acts directly on the heart and from the time it is administered until death is no more than three minutes. Our method can be made in a crowd, in a store, or on the street, for we use injections and just the piercing of the flesh with a tiny needle syringe is all that is required and any doctor will claim heart disease unless the body is examined.

We never make a second demand on anyone. That is our oath and the Hindoos that command never fail. There are twelve of us all told and we all know your family history well. So Friday night at 8 o’clock sharp be in front of the theater with a newspaper in your left hand and a package with your money in the right hand, so the transfer can be quickly made. And you will never hear from us again, for we never ask for a second amount. That you have our oath for.

We are bound together with the oath of our blood. If you make one move of treachery you will be dropped in your tracks. We swear.

The amount is not much to you in comparison to your dear one, so we will expect you on time, but if you are not there (and alone), then beware, for you will only invite execution.

We will be there well-guarded to fight to the death any and all who try to alter our plans, so do not let us have to make an example of you, the first in the city we have asked a favor of.

Do not forget your instructions. Newspaper in right and package in the other. Our words to you will “Is this the package?” Then you will hand it over and we will go about our business and you do the same.

THE RAVENS

P.S. The money must be in paper money and bills no larger than $50.

A highly successful businessman from the gilded era of ruthless clashes between striking labor and strikebreaking capital, James O’Brien Gunn was inclined to laugh the whole thing off as a joke. (“He calls himself The Raven? Really, now! Balderdash!”). Nevertheless, Gunn turned the letter over to the police. This was despite the fact that the banker was publicity shy after that highly embarrassing business of his half-brother’s embezzlement and bigamy which had made scorching newspaper headlines just two years previously. Let me detour a bit to detail this episode, the first of the Gunn family’s which ever, as far as I am aware, touched on criminality.

Part Two: The Near Fatal Love of Gertrude Fontham

In his day James’ father, Canadian corn merchant Daniel Charles Gunn, had sired nine children by two successive wives. One of these children was James’ twenty-one years younger half-brother, William Ellis Gunn. William, a popular, gregarious clubman and generally esteemed “good fellow,” had appeared in New York in 1905, taking over management of the newly-built Schuyler Arms apartments on tony Riverside Drive. Within a year, the bluff, bearded, thirty-five-year-old “Captain,” as he was known, had hired twenty-one-year-old Gertrude Fontham as his stenographer. Gertrude, reputedly a dainty, dark-haired, dark-eyed beauty, was the belle of her little corner of Harlem—or perhaps one should say belle dame sans merci. In October 1905, two young men, William Wood and Lester Finley, roommates on the top floor of a Harlem apartment house, had fought what the press termed a “duel” over “Gert,” with Willie Wood, as he was regrettably known informally, nearly killing Dwight in the affray. Some months after that lamentable affair, Joseph O’Reilly, brother of prominent criminal attorney Daniel O’Reilly (he would defend millionaire Harry Thaw, the 1906 murderer of Stanford White, among other privileged celebrity defendants), came to believe that he himself was engaged to Gertrude, only to receive a very rude surprise indeed when the comely stenographer without warning married her boss in October 1907. William and Gertrude promptly went off to enjoy a honeymoon in Europe, leaving the owners of the Schuyler Arms to discover ruefully that William had taken $5400 out of the hotel’s cashbox to fund the couple’s happy journey. Police in various European cities were alerted to keep on the lookout for the honeymooners.

In his day James’ father, Canadian corn merchant Daniel Charles Gunn, had sired nine children by two successive wives. One of these children was James’ twenty-one years younger half-brother, William Ellis Gunn. William, a popular, gregarious clubman and generally esteemed “good fellow,” had appeared in New York in 1905, taking over management of the newly-built Schuyler Arms apartments on tony Riverside Drive. Within a year, the bluff, bearded, thirty-five-year-old “Captain,” as he was known, had hired twenty-one-year-old Gertrude Fontham as his stenographer. Gertrude, reputedly a dainty, dark-haired, dark-eyed beauty, was the belle of her little corner of Harlem—or perhaps one should say belle dame sans merci. In October 1905, two young men, William Wood and Lester Finley, roommates on the top floor of a Harlem apartment house, had fought what the press termed a “duel” over “Gert,” with Willie Wood, as he was regrettably known informally, nearly killing Dwight in the affray. Some months after that lamentable affair, Joseph O’Reilly, brother of prominent criminal attorney Daniel O’Reilly (he would defend millionaire Harry Thaw, the 1906 murderer of Stanford White, among other privileged celebrity defendants), came to believe that he himself was engaged to Gertrude, only to receive a very rude surprise indeed when the comely stenographer without warning married her boss in October 1907. William and Gertrude promptly went off to enjoy a honeymoon in Europe, leaving the owners of the Schuyler Arms to discover ruefully that William had taken $5400 out of the hotel’s cashbox to fund the couple’s happy journey. Police in various European cities were alerted to keep on the lookout for the honeymooners.

Fuel was added to the fire a few days later when a San Francisco woman, Phoebe Deming Gunn, spoke to the press, informing them that she was William’s wife and the mother of his five children, meaning that William’s second marriage was bigamous. Her faithless spouse, she declared, had callously deserted his family eight years previously, when he, an officer in the naval reserve, left them to take command of the tug Vigilant in the Spanish-American War and never returned. Bitterly Phoebe insisted: “I shall never give him a divorce…. he should be punished for his treatment of us….it is a terrible stain to rest upon my children….” For his part James O’Brien Gunn refused to answer any of the questions eager San Francisco pressmen hurled at him, including even whether or not he was really William’s brother. It was the confiding Phoebe who confirmed this fact, explaining that of late years it had been he, James, and not William, who had provided her with “kind assistance” (i.e., child support). She had accepted this arrangement, but learning of her husband’s bigamy was the final straw for her. The San Francisco Examiner painted Phoebe as an object of extreme pathos, reporting that she and her children resided “out on the furthest edge of the windswept Richmond district, where the evening fog whips in chill and cold, in a ramshackle house set in the midst of a grove of gloomy eucalyptus trees.”

Ten days later, when William and Gertrude returned from Europe, Jospeh O’Reilly, still pining for his “Gert,” was waiting for them at the dock. After he took Gertrude aside and informed her that William already had a wife and children, the shocked young woman departed with Joseph in a cab, alighting at the law offices of Joseph’s brother. The next day Gertrude and her mother announced to the press that Gert was seeking to annul her marriage. The lawyer handling her case was Maurice Meyer, an associate in the law firm of Daniel O’Reilly. To Meyer, William broke down and admitted that he was indeed a married man, but he insisted that at least a “satisfactory arrangement” had been made concerning the hotel funds he had misappropriated (meaning probably that his brother James had stepped up to the financial plate again). Meanwhile Willie Wood, awaiting trial for assault in the second degree (remember the “duel” he fought over Gertrude), from his prison cell piled on William by spitefully insisting to the press that the bigamist had married Gertrude simply to win a wager which he had made with Wood that he could get his secretary to wed him rather than James O’Reilly. As for Phoebe, aka wife #1, she informed the press that she did not know whether or not she would go to New York to testify in Gert’s annulment suit, explaining that she would be “guided entirely” by the advice of her kindly brother-in-law, James O’Brien Gunn. “All I have to say is this,” she added bluntly. “I hope [William] will get all that is coming to him.”

Ten days later, when William and Gertrude returned from Europe, Jospeh O’Reilly, still pining for his “Gert,” was waiting for them at the dock. After he took Gertrude aside and informed her that William already had a wife and children, the shocked young woman departed with Joseph in a cab, alighting at the law offices of Joseph’s brother. The next day Gertrude and her mother announced to the press that Gert was seeking to annul her marriage. The lawyer handling her case was Maurice Meyer, an associate in the law firm of Daniel O’Reilly. To Meyer, William broke down and admitted that he was indeed a married man, but he insisted that at least a “satisfactory arrangement” had been made concerning the hotel funds he had misappropriated (meaning probably that his brother James had stepped up to the financial plate again). Meanwhile Willie Wood, awaiting trial for assault in the second degree (remember the “duel” he fought over Gertrude), from his prison cell piled on William by spitefully insisting to the press that the bigamist had married Gertrude simply to win a wager which he had made with Wood that he could get his secretary to wed him rather than James O’Reilly. As for Phoebe, aka wife #1, she informed the press that she did not know whether or not she would go to New York to testify in Gert’s annulment suit, explaining that she would be “guided entirely” by the advice of her kindly brother-in-law, James O’Brien Gunn. “All I have to say is this,” she added bluntly. “I hope [William] will get all that is coming to him.”

Certainly, young Willie Wood got something coming to him. In August 1908 the amorous young dentist, having been found guilty of assaulting his roommate and close friend Lester Dwight, an electrical engineer and manager of the Cortlandt Telephone Exchange (they had been nicknamed Damon and Pythias in reference to the extreme closeness of their friendship), was sentenced to a term of hard labor in Sing Sing Prison for three to five years. “You might have been on trial for homicide,” the judge sternly reminded the defendant.

Still brokenhearted over his loss of Gertrude, Willie told the press that it little mattered to him where he was housed, in prison or out of it, but that he still believed that he had acted in self-defense when he shot Lester three times. “It is true we had quarreled over the girl,” he explained, and things came to a head in October 1905, after Lester discovered a love poem which Willie imprudently had written to Gert on the back of some piano sheet music to a tune called “My Little Dearie.” However, Willie added, if Lester “hadn’t thumped me over the head with his umbrella as I lay in bed, I should never have drawn my pistol. Even then, he had as good a chance as I, for he was armed and I was wounded once in the head.” Soon five pistol shots, all fired by Wood, rang out in the night, bringing alarmed tenants scurrying up to the young men’s rooms. There they found Lester lying on the floor with blood gushing from his mouth, chest and thigh, and Willie standing over him with a gun. “The woman, the woman, the woman!” was all Lester could moan piteously to onlookers, as Willie admonished him to remember that he was a gentleman and refrain from naming the lady’s name. Police tumbled to the identity of the woman in question anyway, however, when they discovered a will that Willie had made out before the “duel,” in which he left $5000 to Gertrude $5000 and a mere $1000 to his mother, wardrobe mistress at the Belasco Theater, with the proviso that Gertrude not marry within a year of his death. There was also a copious amount of “very saccharine poetry written by the sentimental dentist [which he] dedicated to the young woman,” the press noted amusedly. Things like this “duel” between two supposedly sensible young professional New Yorkers, which fueled news stories for three years, were all welcome grist to the maw of the scandal mill.

Did William Ellis Gunn ever get what was coming to him? Not by the lights of Phoebe, anyway. The bigamist appears never to have served any jail time and he reconciled with Gertrude, with whom he lived until his death in 1942. Between 1908 and 1914 Gertrude bore him three children to go along with the five Phoebe had given him, in the process thickening her figure, while William began to appear not merely fatherly but grandfatherly, though he served in the navy in both world wars. Theirs appears to have been a happy union, legitimate or not. Sometimes crime does pay.

Part Three: The Ravens Get Their Wings Clipped

Crime emphatically did not pay, however, in the case of the would-be criminal gang known as The Ravens. If James O’Brien Gunn successfully extricated his half-brother from his own difficulties a few years earlier, he proved no less able in routing The Ravens. Gunn was a wealthy man, but he was not about to turn over $3000 (about $100,000 today) to some grandiose extortionists writing fantastically of Hindoo poisons undetectable to science. When a representative of The Ravens telephoned Gunn at his home on the evening on which he had been ordered to deliver the money at the theater, he was forcefully told by Gunn himself in no uncertain terms that he had better “forget it.”

Crime emphatically did not pay, however, in the case of the would-be criminal gang known as The Ravens. If James O’Brien Gunn successfully extricated his half-brother from his own difficulties a few years earlier, he proved no less able in routing The Ravens. Gunn was a wealthy man, but he was not about to turn over $3000 (about $100,000 today) to some grandiose extortionists writing fantastically of Hindoo poisons undetectable to science. When a representative of The Ravens telephoned Gunn at his home on the evening on which he had been ordered to deliver the money at the theater, he was forcefully told by Gunn himself in no uncertain terms that he had better “forget it.”

Despite Gunn’s refusal to play along, San Francisco police detailed Detective Bunner to wait outside the Van Ness Theater on the 23rd, ready to pounce on anyone suspicious. No such person appeared, prompting the police to speculate that Bunner had scared off the extortionist. However, three days later almost identically worded missives from The Ravens were received by Rudolph Spreckels, youngest son of California “Sugar King” Adolph Spreckels, and his independently wealthy wife Eleanor. A less familiar detective by the name of Spalding was detailed to await outside the Spreckels mansion, along with two additional detectives by the names of Murphy and Proll, who stayed out of sight. They were all present when a young newsboy, George Demartini, rang at the mansion’s door and was given a package by the Spreckels’ butler. The policemen followed the boy and saw him board a streetcar in company with a slightly built, brown-haired man in a bowler hat, around thirty years of age. Spalding followed the pair onto the car, where he overheard them haggling over the boy’s payment for receiving the package. Becoming suspicious of Spalding’s presence, the man then loudly denied to the boy that he had ever offered him money and refused to take the package. When the man and boy alighted from the car, the cop followed them and placed both of them under arrest. Then at the police station, the San Francisco Examiner ominously noted, “the sweating began.”

After holding out for several hours, the would-be master criminal collapsed and tearfully confessed to the crime of attempted extortion of James Gunn and the Spreckels. There was no gang known as The Ravens, the whole plot having been carried out by him alone: Benjamin Wellington Soule, a twenty-eight-year-old unemployed cook who resided with his wife at a small Victorian row house at 3278 West 21th Street. He had turned to his criminal scheme on account, he explained, on account of his having been out of work and because, in his words: “My mind had been fired by reading cheap detective stories.” After questioning his wife, police concluded that she knew nothing about the affair, but Soule was taken to the city prison and placed in solitary confinement.

Not long before his trial in the summer of 1909, Soule gave an interview to a representative of the San Francisco Examiner, in which he attempted, in an obvious bid for public sympathy, to explain why he had resorted to posting extortion letters to Gunn and the Spreckels. “Soule Blames Dime Novels For Crime,” blared the resulting headline, over a story in which the author dubbed the accused extortionist “one of the most emotional dabblers in crime that the police have had to deal with in some time,” who calculatedly was displaying himself “in the role of a sentimental sinner.” For the modern fan of crime fiction, Soule’s comments on the crime fiction of his own era, from over a century ago, are particularly fascinating.

As his later prison photos show, Benjamin Soule was a slight man of 5’8” and 137 pounds with longish brown hair (before his head was shaved), long nose, large ears, big chin, cupid’s bow mouth and prominent blue eyes that were both sad and soulful—pun not attended. To my mind he bears a resemblance to former Saturday Night Live cast member and perpetual Sad Sack type Kyle Mooney.

Sobbingly Soule spun out his sad story to the man from the Examiner:

I never thought I’d come to this….I never thought of arrest. I had dreams of making a lot of money quick and easy, and I went ahead with my plans with no thoughts of detection.

Desperation drove me to blackmail. I had been out of work for months, and I was compelled to see my wife leave home every day and work in my stead. I never could think of that without bitter feeling.

I think a great deal of my wife. I married her two years ago in Minnesota, where I had gone from New York in search of work. I am a lithographer by trade and I was led to travel West because of the dull times in the East. [He is referencing the devastating Panic of 1907.]

For a time I did very well in Minnesota, but shortly after my marriage I began to have another run of poor luck. I was eventually compelled to take whatever work offered itself and filled jobs as cook, waiter, dishwasher and other places around restaurants.

From Minnesota my wife and I went [in 1907] to Butte, Montana, where I worked for a time as a cook. We then went to Spokane and from there to Wallace, Idaho.

We came to San Francisco from Wallace last December [1908]. I was able to secure work as a cook after arriving here but I eventually lost two different places I had and found myself without a dollar. My wife then secured work in the Quaker restaurant at Polk and California streets and supported us both….[But] I wanted to see her [stay] home, wearing good clothes like other women and busying herself about the care of the house.

I tramped the streets daily looking for work and applied at every possible place where I thought I could get it. In time I became very discouraged and at a loss to know what to do with myself. I felt so ashamed at seeing my wife working that I could hardly bear to look her in the face. Things became more gloomy for me all the time, and for the want of something better to do I revived an old boyish custom and began reading dime novels and other sensational books.

I want to say right now that I have enough sense to know what a foolish thing reading such stuff is for a grown man. At first the thing was a mere amusement, but as I continued to read, I began to have ideas.

“Why not take advantage of this sort of stuff and make money by it?” I began to say to myself. “People are easily frightened.…”

While I was thinking of this, I came across a story of a secret band of poisoners who were known as “The Ravens.” The story told how they blackmailed wealthy people right and left, and I found it fascinating reading. If I am not mistaken the story is one of the “Nick Carter” series of dime novels, and it was replete with the names of queer poisons and other things that appear mysterious and threatening.

I came to the conclusion that this story would make a model framework on which to build an actual system of blackmail….

I used the name of “The Ravens” in the letters I wrote to Spreckels, his wife and President Gunn of the Mechanics Bank. The letters addressed to these persons, in fact, were almost exact copies of the letters in the story I refer to.

The threats to do away with the threatened persons with secret Hindu poisons if they did not pay the money requested were, of course, made simply for effect. I never had any idea of harming any of the persons I wrote and if they would have ignored my letters, they would have been perfectly safe.

The best proof of this is that I engaged President Gunn in a telephone conversation after sending him one of “The Ravens” letters. He told me I had better forget about him, which I straightaway proceeded to do. It would have been the same with the members of the Spreckels family if they had paid no attention to my letters. I thought that of all the wealthy people in San Francisco I would be able to find a few who could be frightened into giving me money.

I intended to leave with my wife for Minnesota, where her mother is ill. My wife’s father died recently, the old lady is very lonely, and we both wanted to be near her….I intended to keep on writing threatening letters until I got possession of several thousand dollars….I am all there is of “The Ravens.” I wish to God I had never heard of the name.

Rudolph Spreckels, a well-known anti-corruption fighter in San Francisco and righteous—many people in San Francisco would have said self-righteous—scourge of bosses and crooked politicians, was proactive in the prosecution of Soule, getting personally involved in questioning him at the jail after he was arrested and helping to draw up the complaint against him, whereas James Gunn seems to have washed his hands of what he deemed the whole damn silly affair. (Let other fools pay him if they want, seemed to be his attitude.) Indeed, Soule’s defense was that the whole thing had essentially been a joke gone wrong, with no harm done; but, after the defendant had been found guilty of the felony of sending threatening letters, the judge sourly declared that he saw nothing funny about Soule’s “joke.” He pronounced Soule no better than a “footpad,” only more “genteel,” and sentenced him to a four-year term at San Quentin Prison. In the event, Benjamin served two years, during which time he was forcibly employed as a sack inspector at the prison’s jute mill, deemed a ‘hell-hole” and the institution’s “most detested industry.” Just a few months before Soule was incarcerated at San Quentin, a fire engulfed the warehouse, resulting in the death of an inmate. He was paroled in 1911, but not long after this he was arrested on a charge of obtaining $85 under false pretenses. His magnanimous victim was willing to drop the charge, but the prosecution insisted on going forth with the case, resulting in Soule being returned to prison to finish out the remaining two years of his original term (and inspect yet more sacks at the jute mill). He was discharged a year later, in 1912.

What happened to Benjamin Willington Soule after he completed his term of incarceration? Was he reformed, or did he become, like so many in his regrettable circumstances, an old lag destined to be a continual repeat offender? The answer is, unfortunately, that I do not know. The penultimate record I have found of him, a draft registration card, comes from the final year of the Great War, in September 1918, when he, now thirty-nine years old, was living in Chicago and employed as a cook in the Lunch Room of the luxurious La Salle Hotel. As his nearest relative he listed not his wife but Mrs. Ida Hay of Coshocton, Ohio. Twenty-four years later, in the midst of another world war, a Benjamin Soule, age sixty-four, was interred in the cemetery at St. Peters Episcopal Church in Chelsea, Manhattan. I think, though I cannot be certain of such, that this was the earthly end of Benjamin Wellington Soule.

The facts, as I have been able to determine them, seem generally to support the story of Soule’s life as he told it to the San Francisco Examiner. The man came of a perfectly respectable background, despite the fact that the Examiner had gibed at him, in its initial account of his arrest, that the prisoner possessed “the cunning of his class.” Born in the town of Richland in Oswego County, New York on December 1, 1878, Soule was the only child of Florence Bejamin Soule, a farmer’s boy, and Ada Marie Wellington. When Benjamin was a child his parents moved with him to Martinsburg, West Virginia, where Florence opened an agricultural store. In 1884, when Benjamin was a teenager, Florence, Ada having passed away, married Mary Margaret Munn of Coshocton, Ohio, where the Soules had moved some time earlier. In 1900, Benjamin, now twenty-one and still living with his father and stepmother, listed his occupation as “pressman,” which is what he meant when he told the Examiner reporter in jail that he had been trained as a lithographer. In 1907 Benjamin married Marie Elizabeth Erickson in Butte, Montana, where he was employed as a cook at an establishment known as The Grill and had a room downtown in the Morier Block. Of Scandinavian descent, Marie grew up in Minnesota, but she and Benjamin had not married there, as Benjamin claimed in the Examiner interview. Had they run off together to marry in Montana?

When in 1918 Benjamin listed his nearest relative as Mrs. Ida Hay of Coshocton, this was true too, it appears. Mrs. Hay was the wealthy widow of Frank Corbin Hay, a wealthy, beloved and benevolent capitalist of Coshocton, and the younger sister of Benjamin’s stepmother Mary Margaret Soule, who passed away in 1902. (Mary Margaret had died at Ida’s home, her husband Florence by her side.) Had Benjamin been able successfully to go to the widowed Mrs. Hay for money in 1909, all of his troubles would have been avoided. (Presumably his father had died by this time.) It would seem as well that his wife, who had visited him every day in jail, according to the Examiner reporter, her eyes red-rimmed and streaming, had not been able to stick it out over the long haul and had left him.

It was a sad, humiliating fate for a man who seemed intelligent and imaginative, and likely was one of the many descendants of prolific Mayflower passenger George Soule. (These include Dick Van Dyke, Richard Gere and abolitionist Silas Soule, who nobly testified against Colonel John Chivington, the contemptible man responsible for the infamous 1864 Sand Creek massacre of Arapaho and Cheyenne tribespeople in Colorado.) The industrious Soule forbear, who probably (or improbably) was of partial Jewish descent, made a great success of himself in the Plymouth colony. Before setting out for the New World, young George in Holland had worked as a printer’s helper, a pressman like Benjamin if you will, and in this capacity had helped produce Perth Assembly, a controversial book that the Puritans smuggled into Scotland in wine vats, which King James I of England deemed unpardonably subversive. Like George, Benajmin Soule seems to have had imagination and creativity, which admittedly he would have been well-advised to put to better uses. Instead of committing criminal offenses, he would have been better off writing penny-a-word crime fiction for the pulps. Just imagine: Erle Stanley Gardner, George Harmon Coxe, Carroll John Daly, Benjamin Wellington Soule…. Instead, he died forgotten and is only being recalled now because back in 1909 the crime pulps, as he saw it, induced in him a felonious inclination to write some very foolish letters.

Part IV: James Edward Gunn: Deadlier Than the Male

It proved to be not Benjamin Wellington Soule who would become the writer of crime fiction, but rather a grandson of Soule’s world-be victim, James O’Brien Gunn—or President Gunn as Soule respectfully called him. (He gave his nemesis Spreckels no such honorific.) When James Gunn died three years after the affair of The Ravens, at sixty-seven still shy of seventy years of age, he was eulogized as one of the great business leaders of California’s early Anglo days, having been Secretary of the California Pacific Railroad, the Union Iron Works and a “confidential man” of Leland Stanford and the brothers Charles and Edwin Crocker, three of the tycoons responsible for the building of the Trans-Continental Railroad. Back in 1874 at age twenty-nine Gunn, a man clearly on his way up to the top, wed Edwin Crocker’s pretty, precociously artistic, nineteen-year-old daughter Katie, a promising student of noted native German California painter Charles Christian Nahl. However, Katie Crocker Gunn tragically passed away from acute nephritis after only a few months of marriage. By his second wife, Laura Littig Shaffer—daughter of a Baltimore merchant, Frederick (Littig) Shaffer, who had inherited, like they do in books, a fortune in real estate from a relative after compliantly changing his surname (as an adult Laura retrieved “Littig”)—Gunn had four children, including George Alfred Gunn, who wed schoolteacher Ernestine Kraft, daughter of a factory agent, and with her had a daughter and son. These were, in order, Jane Lisette and James Edward Gunn, the latter of whom, named for his renowned grandfather, was born on August 22, 1920 in San Francisco.

It proved to be not Benjamin Wellington Soule who would become the writer of crime fiction, but rather a grandson of Soule’s world-be victim, James O’Brien Gunn—or President Gunn as Soule respectfully called him. (He gave his nemesis Spreckels no such honorific.) When James Gunn died three years after the affair of The Ravens, at sixty-seven still shy of seventy years of age, he was eulogized as one of the great business leaders of California’s early Anglo days, having been Secretary of the California Pacific Railroad, the Union Iron Works and a “confidential man” of Leland Stanford and the brothers Charles and Edwin Crocker, three of the tycoons responsible for the building of the Trans-Continental Railroad. Back in 1874 at age twenty-nine Gunn, a man clearly on his way up to the top, wed Edwin Crocker’s pretty, precociously artistic, nineteen-year-old daughter Katie, a promising student of noted native German California painter Charles Christian Nahl. However, Katie Crocker Gunn tragically passed away from acute nephritis after only a few months of marriage. By his second wife, Laura Littig Shaffer—daughter of a Baltimore merchant, Frederick (Littig) Shaffer, who had inherited, like they do in books, a fortune in real estate from a relative after compliantly changing his surname (as an adult Laura retrieved “Littig”)—Gunn had four children, including George Alfred Gunn, who wed schoolteacher Ernestine Kraft, daughter of a factory agent, and with her had a daughter and son. These were, in order, Jane Lisette and James Edward Gunn, the latter of whom, named for his renowned grandfather, was born on August 22, 1920 in San Francisco.

In those years between the first and second world wars, the era of the so-called Golden Age of detective fiction, the George Alfred Gunn family was well-off and socially prominent in the City by the Bay, employing a governess for the children and a succession of Filipino houseboys to cook and clean. When in 1938 daughter Jane became engaged to Noel Edmund Parker, son of the Episcopal Bishop of Sacramento (the Gunns were Episcopalians), the happy news was reported in the San Francisco Examiner by the newspaper’s hoity-toity society page editor Cholly Francisco. This match did not ultimately come off, sadly, but two years later, her father having expired in the interim, Jane eloped to Reno with mining engineer Leroy Briggs and got legally hitched. The wedding was a small-scale affair, although Jane’s mother Ernestine, who would pass away in 1943, was present and her brother James, as the sole male left in the family, was obligingly on hand to give the bride away to Briggs. After their honeymoon, the couple settled between Frisco and Reno at the onetime frontier mining town of Angels Camp, where locals still dug for gold.

At the time of his sister Jane’s wedding, James Gunn was a student at Stanford University, where he majored in English and was a member of Kappa Alpha fraternity. He was six feet tall and weighed 170 pounds, was brown-haired and blue-eyed, had a great set of sparklers and an infectious grin and wore glasses, though vainly he doffed them for photos. During his senior year in the fall of 1941, when he was only twenty-one years old, young Gunn began writing a novel about mania and murder, partly, it was said as an exercise for an English class and partly to entertain his fraternity brothers. “He certainly didn’t write it for your Aunt Hepzibah,” wryly noted reviewer Reece Stuart in the Des Moines Register, adding, in a reference to Will H. Hays, the man who oversaw the Motion Picture Production Code (or Hays Code), which set out a list of moral guidelines for the censorship of American films: “Neither is he shooting at the movies while the Hays influence remains.”

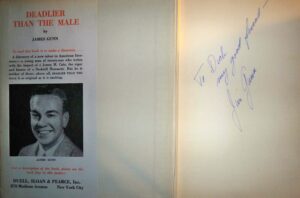

Despite the modest, almost offhand origins of James Gunn’s novel, the college senior, upon completing the manuscript, submitted it successively to four different publishers, the last of which, Duell, Sloan and Pearce, released it through its Bloodhound Mystery imprint (under which they published distinguished crime writers Dorothy B. Hughes and Elisabeth Sanxay Holding) in April 1942, four months before the fledgling author’s twenty-second birthday, under the title Deadlier Than the Male. The novel’s jacket, which included a photograph of the grinning, good-looking neophyte novelist, in its blurb boasted of Gunn’s youth, a tactic which paid off handsomely. Rarely did a first novel receive such critical acclaim.

The Kirkus review, which succinctly summarizes the novel’s plot, was one of the many Male raves noting approvingly just how hard-boiled the young author’s book was:

Tight, tough and chilling, this study in mania and homicide is as vicious and violent and brutal as you could imagine, even with a drilling in Cain and Hammett. It concerns a redheaded brute, Sam Wild, responsible for the death of a Reno whore and a man—and those who love him and tail him. Wild has married an heiress, Georgia, and her stepsister Helen, “deadlier than the male,” spots Wild for what he is. The setting is San Francisco. The characters range from the underworld to the socialites. Gunn has compelling power, though his book is certainly tabu for the tender-minded.

The most notable of these newspaper raves came from the hand of John Selby, a mainstream author and syndicated book reviewer whose “Literary Guidepost” column was carried in scores of newspapers around the country. When James Gunn scored a laudatory notice in Selby’s column it meant that his novel was being nationally embraced not as a mere crime thriller, but as a piece of literature. Noting that his publisher’s blurb compared Gunn to Cain and Hammett (with many other reviewers following suit), Selby declared to the contrary that:

The comparison is so unfair to Gunn as to be ludicrous. This Stanford senior writes better than Cain ever wrote to my knowledge and his humor is not that of Hammett…. Gunn’s humor is far younger than Hammett’s and, for that matter, far funnier…. “Deadlier Than the Male” is the best story of its kind by a writer of comparable age since Maritta Wolf’s “Whistle Stop” (1941), and that’s saying a good deal.

It’s about a murder—several of them. It is not a mystery…. Primarily it is the study of two deadly people, a man and a woman…. And the goddess of the machine is a gorgeous old harridan named Mrs. Krantz who is drinking herself to death with gusto, first in Reno then in San Francisco…. Mr. Gunn has surrounded these principals with a bevy of really good characters, and he has made his unlikely plot seem perfectly reasonable by the simple device of not taking it too seriously. He writes well, with just pace and frequent splashes of brilliance. In other words, he is a “find.”

The raves of Gunn’s novel were too numerous to give more than a brief taste, but here are some additional snippets, most of which contrast the toughness of the book with the dewiness of the author and also emphasize its unexpectedly abundant humor:

The ranks of hard-hitting, he-man novelists, which includes such names as James M. Cain, Dashiell Hammett, William Faulkner, has been increased by the addition of 21-year-old James Gunn…. he can write—excitingly, humorously and trenchantly…. “Deadlier Than the Male” packs a wallop that leaves the reader slightly groggy, and with something of a dark brown taste in his mouth…. It would be hard to imagine an author creating a more unpalatable crew of characters—thugs, drunks, opportunists, charlatans…. the one who really counts…is Mrs. Krantz, blowzy, drunken, ribald Mrs. Krantz, slightly reminiscent of the grandmother in [Victoria Lincoln’s mainstream novel] “February Hill.” Mrs. Krantz is designed along such Rabelaisian proportions, she’s an achievement of which the author may be proud.

Many readers may object to the lightness of touch of this book. It’s rather like writing a “New Yorker” skit about Murder, Inc. [referencing an organized crime group responsible for hundreds of murders between 1929 and 1941, when it was exposed and members were prosecuted.] Personally, we found it a little easier to take than Cain’s unrelieved hard-boiled fiction. —Palm Beach Post

James Gunn has barely reached the voting age. He is a handsome youngster and his first published writing is this surprising novel…. There are murders, several of them….If young Mr. Gunn had been deadly in earnest his story would have been flat. He preferred to be good humored about the whole business…. The result is one of the most sprightly, readable and entertaining stories we have happened upon in a long time. So well is the material handled that the rough spots do not seem rough at all…. Better get this one. —Greensboro News and Record

The author’s youth explains the lusty vigor and uninhibited violence of his story. But it doesn’t explain the adroit ingenuity and cumulative suspense of the plot, the salty jets of dialogue or the persuasive ease with which Mr. Gunn handles a complex narrative…. The story…is squarely in the Janes Cain—Dashiell Hammett tradition, which means that it’s rough, tough and eminently readable…. Those who like murder mixed with appropriate shots of pathology and humor will enjoy it thoroughly. —Robert Barlow, “This World of Books” (syndicated newspaper column)

The author of this first novel is a senior student at Stanford University and is only 21 years old. These are only two remarkable things about this novel. It is not often that so young and inexperienced an author produces a first novel that is both entertaining and horrifying.

‘Deadlier Than the Male” is not a murder story in the popular sense…. It is more of a horror story which manages to be immensely amusing….

[…]

James Gunn has written a novel which cannot fail to be immensely popular. He has a wickedly irreverent sense of characterization and his story which might have become fantasy, remains throughout sufficiently realistic as to be quite credible. The story is packed with tension and humor…. —John Moreland, Oakland Tribune

James Gunn was 21 when he wrote “Deadlier Than the Male.” One is shocked to realize any one only 21 could come to know such people, much less write about them. For this is not a pretty book. If young Gunn gets into his stride, James M. Cain may well look to his laurels, for Gunn packs a literary wallop that calls to mind some of the saltier haymakers of Cain.

[…]

Surely there must have lived the person of Mrs. Krantz. NOBODY could have dreamed her up completely…. There is not a character in the entire book that can be admired, but the reading about them guarantees a couple of hours of nail-biting. —Mildred Dalton (syndicated newspaper column)

Occasionally, not often, does one pick up a book whose first paragraph is so electric that what was meant for a glance becomes a far-into-the-night reading session. Even more rarely is there a book whose dynamo start is sustained throughout. “Deadlier Than the Male” is such a one. This sort of magic is without explanation. It isn’t alone good writing; it isn’t alone plot suspense or exciting characterizations; it is something that comes from within the author, something vital, something super-alive and super-intense.

“Deadlier Than the Male” is not a mystery…. readers of mysteries will find in it more punch, more Machiavellian machinations, and more hair-raising proclivities than in 12 months of most mysteries…. It is an incredible performance, a first novel, begun by a Leland Stanford student as a classroom project. It is incredible because first novels can’t be so expert. But this is. —Dorothy B. Hughes, Albuquerque Tribune

Part V: James Edward Gunn: Queer Noir

Despite all the remarkable superlatives that the novel garnered from newspaper critics and the success which it enjoyed with the book buying public, going through several paperback editions, Deadlier Than the Male is James Gunn’s only known published work of fiction. Like Cornell Woolrich, who back in the Twenties had published a critically praised first novel when he was a lad of twenty-two and a student attending Columbia University, Gunn turned from novel writing to scripting films for Hollywood, possibly dropping out of college to do so, like Woolrich had before him. However, Gunn was not involved with the scripting of the film adaptation of his own novel, which appeared, under the grim title Born to Kill, in 1947. Perhaps this was just as well for him.

Proving rather more squeamish than their brethren in the book biz, appalled film critics largely panned Born to Kill, which starred Lawrence Tierney as Sam Wild and Claire Trevor as Helen Brent, as brutish melodrama and it bombed at the box office. In their notices critics seemed almost to compete with each other in assembling pejoratives with which to denounce the film. Sneered Herbert Cohn of the film in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (ironically recalling the Nick Carter crime stories which had criminally inflamed the imagination of Bejamin Wellinton Soule back in the day of James Gunn’s grandfather): “[Born to Kill is] a sordid story of jealously, selfishness, hate and murder, with all of the fixings of a tawdry dime novel.” Bosley Crowther at in New York Times echoed this sentiment, huffily dismissing the film as a “smeary tabloid fable’ filled with “ostentatious vice” that would only appeal to the “lower levels of taste.” In the “At the Movies” column for the Kansas City Star, the outraged anonymous reviewer chided of the film’s story: “Certainly this sort of stuff is not on the side of morality and is reprehensible.” Topping them all in her ostentatious outrage, Cecile Ager of PM lamented that Born to Kill was “as unsavory and untalented an exhibition of deliberate sensation-pandering as ever sullied a movie screen.” Thankfully at least one reviewer, Banks Ladd, leavened this parade of self-righteous scoldings with a dash of humor, wryly observing in the Louisville Courier-Journal: “The only likable character in the film is a small dog, who whines appealingly when abandoned in a room full of corpses [two, actually]. But the dog appears for only a few minutes, after which the audience is left to the mercies of the actors.”

Professional moralist Jospeh Breen, director of the Production Code Administration, which was tasked with enforcing the Hays Code, objected at the time of the film’s making that Deadlier Than the Male was “the kind of story which ought not to be made because it is a story of gross lust and shocking brutality and ruthlessness.” In the state of Ohio, as well as the cities of Chicago and Memphis, censorship boards prohibited theaters from showing the murder flick on account of its alleged indecency. Its reputation was further damaged the next year when it was implicated in the notorious trial of Howard “Howie” Lang, a twelve-year-old adolescent who in Chicago brutally slaughtered Lonnie Fellick, a seven-year-old boy, polishing him off with a switchblade and chunk of concrete while another boy, nine-year-old Gerald Michalik, at Lang’s direction held down Fellick’s flailing legs. (According to the press, reticent concerning sexual matters, the three boys had earlier engaged mutually in “acts of perversion” as well.) Lang’s lawyers claimed that the boy had watched Born to Kill just three weeks prior to the 1947 murder, temporarily triggering in him a fit of homicidal mania. Back in 1909 Benjamin Wellington Soule had made a similar argument when he blamed a Nick Carter dime novel for inspiring him to send extortion letters to wealthy San Franciscans, but the jury did not buy it then and the jury did not buy it four decades later, in 1948. At his trial Lang was found guilty and sentenced to twenty-two years in prison, but on appeal the Illinois Supreme Court reversed the decision and ordered a new trial. There the beneficent presiding judge, who was hearing the case without a jury, concluded that Lang’s poor upbringing along with his addiction to murder mysteries, crime movies and comic books had rendered him “unable to determine right from wrong.” The judge ordered that the adolescent, who was now fourteen, be given a new start in life at a Catholic school under another name.

Unfortunately, Howie Lang himself was not one to let bygones be bygones. In 1951, Lang, now sixteen, was arrested for beating into insensibility with a chain Gerald Michalik, the pal who had testified against him at his trial. This time around Lang was sentenced to eleven months in prison, during which time he staged what was termed a “3-day revolt in his cell.” When Lang finally walked out of prison in 1953, telling the press that he did not want any help from anyone, Warden Frank Sain lamented of the eighteen-year-old: “He has been a very disappointing prisoner to work with.”

What James Gunn made of all this brouhaha over the film version of his novel I do not know. His own first screenplay credit, a solo one, was for the more anodyne 1943 murder mystery Lady of Burlesque, which starred Barbara Stanwyck in the title role. This film was an adaptation of stripper Gypsy Rose Lee’s 1941 bestselling murder mystery The G-String Murders, a pithy and racy novel that was rather like Gunn’s, only even more commercially successful. Hunt Stromberg, the independent producer of The G-String Murders, had been immediately interested in filming Deadlier Then the Male, and presumably came into contact with the author that way. He spoke warmly of Gunn’s participation in his film, telling the press that screenwriter was “an outstanding example of the opportunities motion pictures offer a young man of 22 with imagination and writing talent today…. He looks at the world through the eyes of a young modern. He has no sympathy for a phony, for sham or theatricals. He thinks and writes in that frank, down-to-earthy, lighthearted manner that is so much needed today.”

Reviewers like Philip K. Scheuer praised Gunn’s “tongue-in-cheek script” (along with director William A Wellman’s “slightly derisive direction”) for “simulating the odorous backstage atmosphere of [a burlesque theater] without actually showing anything objectionable, at least that you can put your finger on…. The girls are prettier and shapelier [than in real burlesque], the jokes innocuous and the striptease antiseptic—but the feel is still there.” One had to consider the strictures Gunn worked under in scripting this film. As Scheuer noted, “the picture was first banned and then passed, with deletions, by the Legion of Decency.” Censor Breen even complained about the use of a G-string as a murder weapon (strippers are strangled with it), complaining that the article was altogether too “intimate” a piece of feminine apparel.

One thing James Gunn managed to do, like Dashiell Hammett had before him in his classic hard-boiled novel The Maltese Falcon (1930), was to slip into the Burlesque script the word gunsel, in its true meaning of catamite, defined as a young man or boy “kept by an older man for homosexual practices.” (The word actually first appeared in the serialization of Falcon in Black Mask in 1929.) Explicit references to homosexuality were frowned upon in American entertainment media and explicitly proscribed from films by the Hays Code in 1934. However, censorious editors and the like thought that gunsel meant a gun-armed henchman of a crook and, guided by this misimpression, allowed the word to remain both in Hammett’s novel and the classic film adaptation, directed by John Huston and starring Humphrey Bogart as Sam Spade, which premiered in October 1941, when Gunn was writing Deadlier Than the Male. In the film Spade sneeringly refers to young thug Wilmer Cook (Elisha Cook, Jr.), lackey to the obviously queer Kasper Gutman (Sidney Greenstreet), as a gunsel. Two years later in Lady of Burlesque, the word appears again, in its original meaning, when an angry stripper sneers at her boyfriend: “Big Louie the Grin! Turns gray when he sees a cop, like a gunsel.” The stripper here clearly is using the word, like Sam Spade had in The Maltese Falcon, as a synonym for pansy or fairy, words Gunn had gotten away with using, by the way, in his novel. As far as I know, Burlesque is the only film that followed Falcon in this correct usage, with other films which included the word using it to mean gunman. On the other hand, Gunn deleted the bit from Gypsy Rose Lee’s book where a lesbian cop amorously hits on her character, though in the film the actress who briefly portrays the policewoman certainly is depicted in full “dyke” battle mode, if you will.

In contrast with Born to Kill, Lady of Burlesque in playing it safer with its script made a big hit at the box office. Gunn was unable to capitalize on the film’s success, however, for by the time Burlesque premiered in May 1943, he had been inducted into the army. After he returned to civilian life in 1945, he would garner only one other screenwriting credit in the Forties. This was for the film The Unfaithful (1947), a reworking of the Bette Davis murder melodrama The Letter, starring Ann Sheridan in the Davis role, which adopted a modern attitude to wifely adultery. Gunn co-wrote the screenplay with noir author David Goodis.

In the 1950s Gunn worked with other writers on additional film scripts, including those for the Joan Crawford marital melodrama Harriet Craig, (1950), itself another updating of an older film; the grift film Two of a Kind (1951), starring Lizabeth Scott and Edmund O’Brien; Affair in Trinidad (1952), a mystery which reunited Gilda stars Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford; and All I Desire (1953); a Douglas Sirk period noirish melodrama starring Barbara Stanwyck. Like so many other Hollywood writers in the Fifties, he then found steady work in television. During the early to mid-Fifties, he wrote thirty-five episodes for such TV anthology series as Fireside Theater, Chevron Theater, The Pepsi-Cola Playhouse and Studio 57. Perhaps his most notable television job was co-writing six episodes of the critically-praised series Checkmate, which was set and San Francisco and created by Eric Ambler. (Gunn co-scripted these episodes with Ambler.)

During these years, Gunn’s sole film screenplay was for the Oscar-nominated melodrama The Young Philadelphians, a sudser starring Paul Newman which opens with a scene of a Main Line mama’s boy socialite, an evident self-hating queer played by Adam West of later Batman fame, miserably explaining to his bride on their honeymoon that he cannot consummate their wedding and then running out on her. James Gunn may have hoped that the hit flick might revive his flagging film career. At the time of the picture’s opening, it was reported that he and another writer with a very similar name, the late Lawrence, Kansas science fiction writer James Edwin Gunn, had taken out an ad in a Hollywood trade paper, explaining to the public that they were in fact different people. “He is now, and has been since the Ice Age, in Hollywood,” the text dryly explained about James Edward Gunn. This was Gunn’s last film work, however. Indeed, it is claimed in some sources that Paul Newman hated the Young Philadelphians script and brought in blacklisted writer Dalton Trumbo to doctor it.

Gunn’s final aired television script was for a 1965 episode of the William Faulkner inspired drama The Long, Hot Summer. He died in Los Angeles the next year, on September 20, 1966, when he was only forty-six years old. The circumstances of James Gunn’s death—and, truth be told, much of his life–remain frustratingly unclear. When Black Mask reprinted Deadlier Than the Male in a typo-ridden edition in 2009, reviewers of the novel praised it while expressing perplexity over the obscurity of the author. “Little is known of his life, and he remains a tantalizing mystery,” observed Tony D’Ambra” at FilmNoirsnet back in 2010. “Nobody seems to know anything about him,” echoed blogger Bill Chance back in 2011. Over the decade, however, nothing seems to have been done to rectify the matter. “Searching for biographical information on Gunn is a futile endeavor,” concluded author and academic Sean Carswell in 2019.

James Gunn’s sister Jane preceded him in death at the old goldrush town of Nevada City, California four years before his own demise. Aged forty-six years like her brother when she expired, she left behind her husband of twenty-two years, Leroy Briggs, but no children. James, who seems never to have married, evidently was similarly childless at his death. It is completely speculative on my part, but I wonder, given his life circumstances and his fiction and film writing–which so often is dominated by strong female characters and frequently evinces, to my mind anyway, a camp sensibility–whether James Gunn was gay. It would be interesting if so, because noir, with a few exceptions like Cornell Woolrich, is so associated with the “he-man” tough school of crime writing. Yet even many critics at the time noted the queer, pun intended, juxtaposition in Deadlier Than the Male of Gunn’s humorous, surrealistic writing with sharp bursts of violence and brutality, as well as the superb portrayal of Mrs. Krantz, that indomitable avenging angel and drunken old hag—a camp gay icon type character if ever there were one.

In 1950 French publisher Gallimard under its influential Serie noire imprint, which Gallimard had established five years earlier, reprinted Deadlier Than the Male, under the title Tendre femelle (Tender Female) as the fiftieth book in its series. A year after Gunn’s obscure death in 1965, Leftist French philosopher Gilles Deleuze on the occasion of the publication of the thousandth novel in the series, produced an essay, “The Philosophy of Crime Novels,” in which he named Gunn’s book as a “marvelous work” and “my personal favorite” from the series. In “A Lure for the Devil,” an essay by Sean Carswell on Deadlier Than the Male which the LA Review of Books published in 2019, Carwell highlights the comical, surrealistic quality of Gunn’s novel, never using the word camp but depicting the book as a noir parody. Carswell frequently cites Gilles Deleuze’s 1966 essay, in which, he notes, Deleuze named Deadlier than the Male “his favorite example of what the best crime writing can do,” because its absurdist parody rejects the sense of ultimate rationality and order that one finds in the traditional crime novel–even the hard-boiled novel. To quote Deleuze: “The most beautiful works of La Serie Noire are those in which the real finds its proper parody, such that in its turn the parody shows us directions in the real which we would not have found otherwise.”

Sean Carswell writes that despite the book’s title, its depiction of the femme fatale is ironically subversive of (straight male) genre tropes:

Rather than describing a sexy, seductive femme fatale, Gunn creates a fabulous one. She’s far closer to Truman Capote’s Holly Golightly than she is to, say, Raymond Chandler’s Velma Valento. The third-person narrative voice reads like it comes from a gay man who wants to go clubbing with her.

This voice provides a clever counterpoint to the typical characterizations of femmes fatales…. the femme fatale that readers were very accustomed to in the 1930s and 1940s [was] the woman whom the narrator or narrative gaze wants both to sleep with and to blame for all of his misdeeds. Gunn’s parodic portrayal of a femme fatale highlights the absurdity of this trope. He doesn’t want to sleep with her. God, no. He wants to help her pick out that marvelous outfit. And if that outfit should drive a man crazy, well, it was probably a short trip there.

When it came to marketing the film version of Deadlier Than the Male, it is noteworthy that the change of title to Born to Kill and the tag line (The coldest killer a woman ever loved!) together place emphasis on the male character, Sam Wild, as protagonist, rather than Helen Brent. I would say to the contrary that in Deadlier Than the Male the sole protagonist clearly is Helen Brent, the film’s putative femme fatale, with Mrs. Krantz as antagonist or nemesis and Sam Wild as Helen’s would-be homme fatale, his presence in her life peeling away her layers of civility and spurring her on to worse and worse actions. In short, it is not Helen’s maleficent impact on Sam that the author is interested in so much as Sam’s maleficent impact on her. Helen’s lead status is diluted in the film, as is the role of Mrs. Krantz, although there is enough left of her part that character actress Esther Howard, who plays her in the film, is able to steal every scene in which she appears. (Howard’s name is not even included on the film’s posters.)

Moreover, as Carswell urges, James Gunn’s parody goes beyond subverting the traditional depiction of hard-boiled femme fatale: “It’s not enough for Deleuze when crime novels simply parody the form or the genre, the best novels parody what we perceive as the real. Therein lies the power of Deadlier Than the Male: it takes our ideas of an orderly, just, civilized society where people act on rational motives; it eviscerates those ideas; and leaving us laughing at the rubble.” All of this is vitiated in the film version, especially with its soft-pedaled, traditionally moralistic ending (i.e., crime does not pay). Some modern reviewers have simply been left confounded, even repelled, by Gunn’s subversive novel. ‘It’s an odd, crazy book,” observed bemused blogger Bill Chance in 2011. “[T]he plot is like a big twisted knot of desperation and evil, stretching from [Reno] to Frisco…. I was able to get through the book in one day. [Now] I need to find something different [to read], maybe even something a little uplifting. After reading this one…I feel sort of dirty.”

Gunn’s possession of an iconoclastic queer sensibility would help explain how this novel came to be written as it is, but perhaps Gunn simply looked back with sardonic amusement at the criminal follies which had occurred in the lives of his own grandfather and great-uncle a decade or so before he was born. What could be more absurd than his grandfather getting a letter threatening death by a deadly, undetectable Hindu poison administered by the hands of an imaginary criminal gang called The Ravens, except the San Francisco police taking the letter so seriously as to ruin an impetuous man’s life over it? What could be more surreal than the idea of Gertrude Fontham, that supposed femme fatale of Harlem, driving a pair of foolish men to a so-called duel and yet another to acts of embezzlement and bigamy, before she settled down to a bland, everyday life of domesticity and children with a man who looked like her doting grandfather? What could be more unjust than Bejamin Wellington Soule’s silly letters resulting in his losing three years of his life to hard labor in a bestial jute mill, while William Ellis Gunn a couple of years earlier walked off legally unscathed after committing embezzlement, desertion and bigamy? And, one might add, what could be more ridiculously simplistic than to blame a film-noir for one boy’s horrific murder of another, rather than societal ills or individual psychosis? Perhaps James Gunn could only look back and laugh in the face of such cosmic injustices and absurdities, rather than piously don black and shed traditional tears. After all, as another noir film, produced by Gunn’s cinematic impresario friend Hunt Stromberg, warned in 1949, it was too late for tears.