Then—in my childhood—in the dawn

Of a most stormy life—was drawn

From ev’ry depth of good and ill

The mystery that binds me still—

—from Edgar Allan Poe’s “Alone”

Having completed just forty years of what was without question a most stormy life, Edgar Allan Poe took leave of this realm early Sunday morning, October 7, 1849. Nobody knows precisely why. Indeed, like so many aspects of his life, his death has been the topic of endless debate, conjecture, speculation, guessing, and second-guessing. Nobody can tell you with anything resembling certainty why, while traveling from Richmond to New York, he ended up in Baltimore. Nobody can tell you what happened to him during the missing days between his last sighting in Richmond on the evening of September 26 and his reappearance outside an Election Day polling place in Baltimore on the damp, chilly afternoon of October 3. Nobody has ever solved the identity of the person, Reynolds, for whom Poe supposedly called out for hours before he died at the Washington University Hospital of Baltimore. Nobody has ever produced conclusive evidence, or so much as a first cousin to it, regarding the cause of the delirium generally described as “congestion of the brain,” “cerebral inflammation,” or “brain fever.” Even the melodramatic and rather pat last words attributed to him—“Lord help my poor soul!”—have been called into question. The source for that dying utterance is a shaky witness who trafficked in contradictory testimony, attending physician John J. Moran (who may or may not have been in attendance at the time of death). The one thing that can be said with absolute certainty is that Edgar Allan Poe died at the age of forty years, eight months, and change because he stopped drawing breath. Or, to put it somewhat more poetically, as he wrote in one of his poems, “For Annie”:

The danger is past,

And the lingering illness

Is over at last—

And the fever called “Living”

Is conquered at last.

Poe’s death has become so much a part of his mystique that it is often the first topic broached by visitors to the major destination sites devoted to the writer: the Edgar Allan Poe House in Baltimore, where, in the early 1830s, he discovered both a family that accepted him and a gift for short fiction; the Edgar Allan Poe Museum in Richmond, the city where he did much of his growing up and where, in 1835, he launched his often-controversial career as an influential literary critic and magazine editor; the Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site, the only one of his five Philadelphia residences from 1838–44 still standing; and the Edgar Allan Poe Cottage in the Bronx, his rented home from the spring of 1846 until his death. “I would be a millionaire if I had a dime for every time I’ve been asked how he died,” said Steve Medeiros, a Poe scholar and former National Park Service ranger whose regular duties included greeting those who passed through the door of the Philadelphia house.

During an interview conducted for this book, Matthew Pearl, author of the acclaimed 2006 novel The Poe Shadow, observed, “His biography doesn’t really start where most biographies traditionally start, with his birth; it starts with his death.” Is there a hint here of Poe’s observation that romance writers could learn from Chinese authors who had “sense enough to begin their books at the end”?

The ongoing fascination with his death is understandable. It is, after all, one of the great literary stage exits of all time—right up there with Molière, the actor-playwright who, suffering from pulmonary tuberculosis, overcame an onstage collapse and hemorrhage to finish a final performance before dying a few hours later in 1673, and Mark Twain, who correctly predicted that, having been born when Halley’s Comet visited the Earth in 1835, he would die when it returned in 1910. Poe’s death, however, takes on added significance because it is undeniably one of the major factors keeping him alive as one of the most instantly recognizable writers of all time and the most-read American author around the world. Here, too, Twain is in the running, but Poe probably is better read while Twain is more frequently quoted (although often inaccurately). Poe’s death is not only a source of continuing fascination; it is also symbolic of what became his deeply entrenched literary identity. He died under haunting circumstances that reflect the two literary genres he took to new heights.

Poe might as well have been writing his own epitaph with the first line of his story “The Assignation”: “Ill-fated and mysterious man!—bewildered in the brilliancy of thine own imagination, and fallen in the flames of thine own youth!” His death is a moment shrouded in horror. Poe died in a lingering, painful manner that would not have been out of place in one of his own incredibly influential terror tales. It is also a moment surrounded by mystery. It is, in fact, a double-barreled mystery. What was the cause of Poe’s death, and what happened to him during those missing days before he was found “in great distress” on the streets of Baltimore, wearing ill-fitting clothes that were not his own? Why did he look so disheveled, his hair unkempt, his face unwashed, and his eyes “lusterless and vacant”? Pale and alternately described as both cold to the touch and burning up with fever, Poe in his delirium held conversations with what resident physician Moran said were “spectral and imaginary objects on the wall.” Sound like the description of a character in one of his stories? It also sounds like a mystery worthy of Poe’s master detective (and the model for so many super sleuths to follow), C. Auguste Dupin. Here, to be sure, is both mystery and horror aplenty. “The haunted writer and the father of the detective story leaves us with grim mysteries that have defeated every attempt to solve them,” Medeiros said. “It’s almost as if a publicist stepped in and said, ‘Hey, you know, the best thing for you to do for the career is to die under mysterious circumstances at forty.’”

It has been suggested that one reason Poe was drawn to the horror genre was an attraction to the American nineteenth-century death culture, which resulted in increasingly elaborate mourning rituals, grander and more extensive cemeteries, and heartrending songs and poems dwelling on grief and loss. Death most assuredly was a constant companion throughout Poe’s life. So perhaps it’s fitting that something of a death culture has developed around him. An astonishing number of theories have been pursued but never proven examining both the missing days and the cause of death. The long list of candidates for what carried him off includes binge drinking, rabies, murder, a brain tumor, encephalitis brought on by exposure, syphilis, suicide, heart disease, carbon monoxide poisoning from illuminating coal gas, and dementia caused by normal pressure hydrocephalus. A new “answer” seems to pull into the speculation station every couple of years. Hang around that station for any length of time and you’re pretty certain to run into someone claiming he or she has solved the mystery of Poe’s death—unless, of course, that person is blocked out by someone claiming he or she just solved the identity of Jack the Ripper.

Does the investigation that follows settle on a favorite theory of how Poe died? Sure, absolutely. Can this or any other theory be conclusively proven using the most modern forensic tools and methods at our disposal? Well, let’s put that question to a myriad of tests and see where the investigation takes us as we examine Poe’s life through a lens fashioned from the mystery of his death. This is just the opening of the case file, and plenty of leading experts from several fields have been called in to consult. They include Poe scholars, museum curators, medical experts and historians, horror writers, forensic pathologists, best-selling true-crime authors, a specialist in forensic anthropology and archaeology, an actor beloved for his association with Poe, and a pioneering FBI agent. Each had something compelling to say about how Poe may have died but also, and ultimately more illuminatingly, about how he lived. Each had a piece of a challenging puzzle. The horror specialists, for instance, from Stephen King and Anne Rice to Ray Bradbury and Wes Craven, quickly moved beyond stereotype to dwell on the complete writer and complex individual who must have been behind those tales of terror and the macabre. Their ruminations helped bring the real Poe into focus, and that hasn’t been easy, since our view of him has been terribly obscured by persistent efforts to keep it in the shadows. Poe might also have been in a prophetic mood when he penned these lines for “Shadow—A Parable”: “Ye who read are still among the living; but I who write shall have long since gone my way into the region of shadows.” So, yes, it starts with his death.

They buried Poe the day after he died, in Baltimore’s small Westminster Presbyterian Cemetery. He was buried again the next day when editor and poet Rufus Griswold’s notorious obituary appeared in the evening edition of the New-York Tribune, opening with the withering lines: “Edgar Allan Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore the day before yesterday. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it.” It went downhill from there. Nursing grudges against Poe, Griswold used the scurrilous obituary to shovel all manner of dirt and mud on his memory, depicting him as immoral, arrogant, unbalanced, dishonest, envious, conceited, and dishonorable. Griswold built on this wildly inaccurate and grotesque picture of Poe, adding even more outrageous charges in later writings. Poe’s drinking had already been acknowledged by his friends and exaggerated by his enemies. And there’s no question that alcohol periodically played the role of Poe’s personal “Imp of the Perverse.” But if you want to start an academic dustup among Poe scholars, bring up the subject of alcohol. There is a lively and ongoing debate on how much he drank and how often. From his college days at the University of Virginia, there were many witnesses who said it took very little alcohol to throw Poe into a state of extreme inebriation. Regardless of how much he drank at one time, the result was the same. It invariably had a devastating effect on his system and his psyche, and recovery usually meant more than just suffering through a morning hangover. The more notorious reports of his public intoxication gave Griswold more than enough ammunition in an era that equated trouble with the bottle to a weakness of character.

Yet Griswold went further, adding the label of drug addict, which, although without foundation or justification, also became an enduring part of the caricature. As an influential anthologist and respected arbiter of literary tastes, as well as the designated editor of the first collected edition of Poe’s works, he was believed by many. So, less than twenty-four hours after being laid to rest in Baltimore, Poe was interred under a noxious pile of distortions, malicious falsehoods, and lies. To Poe’s ardent champion Charles Baudelaire, the French poet and critic, Griswold’s ongoing campaign of character assassination was the crass and hateful work of “a pedagogic vampire.” Casting Griswold in the role of miserable cur, Baudelaire famously asked, “Does there not exist in America an ordinance to keep dogs out of cemeteries?” Nevertheless, Griswold’s brutal and often-despicable attacks on Poe created a false overall impression that, despite the best efforts of scholarly detectives to set the record straight, hasn’t been completely dispelled to this day. “The damage this article did to Poe’s reputation was incalculable,” Arthur Hobson Quinn wrote in his landmark 1941 biography of Poe. Still, it is wise to keep in mind that, in a Poe story, nothing ever stays buried. “In death—No! even in the grave all is not lost,” he had his narrator tell us in “The Pit and the Pendulum.”

They actually did dig up Poe’s body in 1875, reburying his remains in a northwest corner of the cemetery to make room for an impressive new monument. By that time there had been significant blowback to Griswold’s bitter smear campaign, both by Poe’s friends and his growing number of admirers in Europe. Among those leading the counterattack was Baudelaire, who, although passionate in his great admiration for Poe’s work, contributed to the gradually entrenched stereotypes by arguing that Poe’s characters were projections of his personality. It is yet another distortion that has held on as we moved from one century to another to another. Many a junior high school student reading “The Raven,” “The Tell-Tale Heart,” and “The Cask of Amontillado” has been encouraged to confuse Poe with his narrators caught in the grips of morbid obsessions, crippling grief over a lost love, a consuming thirst for revenge, or fixations that threaten to unhinge the mind.

“Poe certainly drew on his life and experiences for his stories and poems, as all writers do,” said Scott Peeples, a College of Charleston professor and author of The Man of the Crowd: Edgar Allan Poe and the City. “But it’s a fundamental misconception to confuse Poe with his narrators. Even with illustrations of ‘The Raven,’ the narrator often is drawn to look like Poe.”

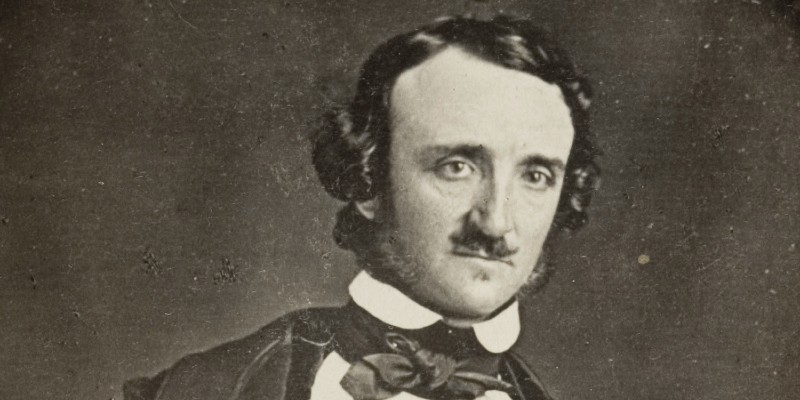

The twentieth and twenty-first centuries certainly had their way with Poe as well, burying him yet again, this time behind a shorthand kind of brand identification adored by Hollywood and the pop culture. He has become our original master of the macabre, the grandfather of all things Goth, the king of horror long before the world had heard of Stephen King. There’s every good chance that the mention of his name conjures an image along those general lines for most Americans. Enduring fame, therefore, has turned into something of a double-edged sword for Poe. On the one hand, that small group of stories and poems has made his name and face instantly recognizable and marketable. You can walk into a bookstore and find entire shelves of Poe items aimed at a wide range of customers. Don’t bother looking for the shelves devoted to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Ralph Waldo Emerson, or any of the other literary contemporaries whose fame was supposed to overshadow and outlast Poe’s reputation. Commercialism may not be the best test of literary merit, but this kind of overwhelming presence can’t be casually dismissed. Surely no author is as relentlessly merchandised as Poe. You’d probably recognize the mustached fellow whose gloomy, haunted face stares at you from T-shirts, coffee mugs, refrigerator magnets, blankets, wall clocks, scented candles, pendants, iPhone cases, earrings, lapel pins, flip-flops, socks, plush dolls, bobblehead dolls, wine stoppers, and even a surprisingly wide assortment of Christmas cards (because nothing quite says merry Christmas like replacing Santa bellowing ho-ho-ho with a raven croaking Poe-Poe-Poe). The e-commerce site Etsy lists more than ten thousand Poe centric articles for sale. You know this Poe. He looks moody, perhaps doomed.

With the pop culture doing its part, Poe at the same time remains the renewable literary force being constantly reintroduced in public and private school curricula from the seventh grade onward. Teachers adore getting to those sections devoted to Poe, and even those students who find reading a chore tend to be delighted with an author who is dismembering corpses, walling up pompous jerks in crypts, slapping poor souls into torture chambers, and stuffing bodies up chimneys. What’s not to love? Poe, the frightmeister, hits them at just the right impressionable age with visions potent enough to fire up the imagination.

“Students from the seventh grade on can intensely identify with Poe because he writes about characters who feel incredibly vulnerable or are haunted by things they’ve done or are stymied by oppressive figures or feel as if violence may come down upon them at any time,” said J. Gerald Kennedy, author of Poe, Death, and the Life of Writing and the editor of A Historical Guide to Poe. “I did a workshop a couple of years ago in Dallas, and so many African American teachers told me that their students especially liked Poe because he talks about that vulnerability, and this really resonates with them. It helps to explain the powerful fascination that students develop with Poe.”

Through it all, ever since Baudelaire and other admirers turned Poe into a tortured genius of an icon, Poe has remained, well, cool, demonstrating enormous street cred with generation after generation. He has an honored spot—top row center—on the cover of the Beatles’ album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. He’s name-checked in John Lennon’s “I Am the Walrus” (“Man, you should have seen them kicking Edgar Allan Poe”), and one of his stories is referenced in Bob Dylan’s “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” (with its advice about “When you’re down on Rue Morgue Avenue”). His works have been given playful twists on The Simpsons, and his spirit has been summoned to help Goth and vampire kids on South Park. “The Tell-Tale Heart” got a Bikini Bottom makeover on SpongeBob SquarePants, and, on Halloween night in 2020, Jim Carrey opened Saturday Night Live as Joe Biden reading an Election Day retelling of “The Raven.” Another of Poe’s most famous poems, “Annabel Lee,” has been turned into song versions recorded by such varied artists as Frankie Laine, Jim Reeves, Joan Baez, and Stevie Nicks. And, although hardly faithful to the writer’s stories and poems (if, in fact, they bear any resemblance to them at all), Hollywood’s Poe-“inspired” films, from Universal classics in the 1930s with Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff to the Roger Corman delights of the 1960s with Vincent Price, have become iconic in their own right. In October 2021, Netflix announced The Fall of the House of Usher, a series based on multiple Poe works.

Yet our vision of Poe remains a blurry one, at best. And here’s the other side of that whole double-edged fame sword. The Poe we know—or think we know—is a grotesque caricature. He’s the sickly, pasty guy with the sunken eyes, huddled over a manuscript in an attic, a raven perched on his shoulder. A red-eyed black cat sits among the cobwebs at one hand, a bottle of cognac at the other. We’ve reduced him to this cartoonish image, letting a small part of his literary output completely frame that distorted perception. It’s like getting a picture of Poe from the reflection in a fun-house mirror. Yes, the stereotype does have some basis in fact. The master of the macabre unquestionably is an essential part of who Poe was. There’s a reason those few stories and poems continue to have such impact. There were platoons of writers trading in the same graveyard territory before and during Poe’s literary prime, but none could approach his sublime skill for summoning feelings of dread, unease, fear, and terror.

“The Goth image of Poe can be limiting, but it sure is enduring because there’s a lot of truth to it,” Kennedy said. “From the very beginning of his career, he’s obsessed with the problem of death.”

Acknowledging this is key to understanding Poe, but letting it completely define him as a writer criminally sells him short as an artist and a person. We are seeing merely one part of this incredibly dedicated and deceptively versatile writer. It becomes just another way we’ve buried Poe—under a mountain of misconception, myth, misunderstanding, and, of course, mystery. Poe, the master of invention, has become an invention.

“There’s almost no relationship between the myth and the man,” said Harry Lee “Hal” Poe, a cousin whose published works include Edgar Allan Poe: An Illustrated Companion to His Tell-Tale Stories and Evermore: Edgar Allan Poe and the Mystery of the Universe. “Very little of what Poe wrote could be classified as horror, and just a part of that is supernatural. Poe had an absolute horror of being typecast. He thought it was important for a writer to display that diversity and show you could write in all sorts of different ways. But it has become the end of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, when the editor has heard the true story and taken down all of the facts, and then tears it all up, saying, ‘When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.’ That’s Poe. He has become a legendary character, and people like the character. It’s one reason people keep reading him, but the real Poe has been lost while the legend is uncritically accepted as fact.”

The real Poe considered himself first and foremost a poet. The real Poe was best known in his lifetime as first a tremendously tough critic, second a poet, and third as the author of tales of mystery and horror. Our perception of Poe has reversed that order. But Poe also wrote a substantial number of satires, hoaxes, and humorous pieces, and, let’s face it, nobody thinks of Edgar Allan Poe as a comedy writer. The man had quite a sense of humor, but that doesn’t fit the myth. “The popular image of Poe is so far off the mark that it borders on the ludicrous,” Poe and Twain scholar Dennis Eddings said. “Poe had a delicious sense of humor. He loved cats, a true test of character, as Mark Twain recognized. And he took his art seriously at the same time he made fun of it, surely a sign of a well-balanced mind.”

Poe also wrote stories that would influence later science-fiction writers. There were essays and journalistic pieces. Many visitors to one of those Poe sites in Baltimore, Richmond, Philadelphia, or New York have crossed the threshold proclaiming, “I love Edgar Allan Poe. I’ve read everything he’s written.” They mean that they have one of those volumes of collected tales and poems, which they’ve read cover to cover. The charitably unspoken rejoinder is, “Really? You’ve read everything? Did you start with James A. Harrison’s 1902 edition, which runs to seventeen volumes?”

“The madman howling at the moon was Griswold’s invention, and, to this day, that invention keeps the real Poe hidden from us,” Hal Poe said. “The real Poe was the life of the party—witty, clever, engaging. He would bring his flute, and he and his wife, Virginia, would perform duets. Poe loved humor, but he had no great love for the horror story, even though he excelled at it. He was courtly, and he had a lot of friends, despite what Griswold wrote.”

We don’t lose Poe the horror writer by disposing of the cartoon image of him and accepting that he had a lively sense of humor and an exacting work ethic. Indeed, by acknowledging the complete artist, we better understand why and how he could take horror to such sublime and terrifying heights.

“The image of Poe has been terribly exaggerated and distorted, but that tends to happen with almost anyone who becomes known for horror: writers, actors, directors,” said Robert Bloch, the horror writer best known for his novel Psycho. “People create their own images of horror writers, and these images often crowd out realities. The problem is that no one looks beyond the gloomy, melancholy images of Poe and sees the guy playing leapfrog in the front yard and laughing himself silly. Nobody thinks of Edgar Allan Poe as a fellow whose mother-in- law called him Eddy. But you have to accept and understand and know that Poe before you can even begin to fully understand the fellow who wrote all of those wonderfully eerie tales that have haunted our imagination for a hundred and fifty years.”

___________________________________

Excerpted from A Mystery of Mysteries The Death and Life of Edgar Allan Poe, by Mark Dawidziak. Copyright, 2023. Published by St. Martin’s Press. Reprinted with permission.