In 1952 a 29-year old Somalian man was hanged at Her Majesty’s Prison Cardiff in Wales by Britain’s best known public executioner Albert Pierrepoint. After a long drawn-out detention, a highly questionable police investigation, and a speedy trial at the Glamorgan Assizes in Swansea, Mahmood Mattan had been found guilty of murdering shopkeeper Lily Volpert in the then notorious Tiger Bay area of the Welsh capital. Despite arguments from his lawyers Mattan was refused leave to appeal by the Home Secretary.

Forty-six years after Mattan’s execution, and 34 years after the death penalty was finally due to increasing public outcries and distaste, the Court of Appeal (the highest court within the Senior Courts of England and Wales) quashed his conviction. Mahmood Mattan became first person in British history to have a murder conviction officially overturned after being executed. Little comfort obviously to the hanged man himself but the record was now clear: Mattan was not guilty. The Britain judiciary had killed an innocent man, a husband, and a father of three. In 1996 Mattan’s family was granted permission to move his remains from the felon’s grave in the prison grounds to the Muslim section of a Cardiff cemetery.

But the trauma and fall out of this miscarriage of justice continued relentlessly damaging more lives. In 2003 Mahmood’s eldest son, Omar, was found dead, seemingly by suicide, on a Scottish beach. As a boy in Wales Omar had believed his father had died at sea until he was cruelly taunted and ostracised about the hanging. It is fair to say that though this sad story reflects poorly on post-war British race relations, the police and, justice system the case has subsequently been largely forgotten and the name of Mahmood Hussein Mattan and his family is little known today in Britain outside of some now very elderly residents of the old Cardiff Docks area.

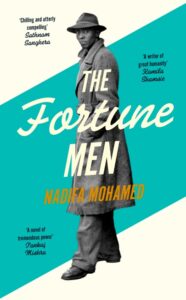

British-Somali author and journalist Nadifa Mohamed has now chosen to tell Mattan’s story and recreate the world of 1950s Cardiff, its multicultural and frenetic Tiger Bay district, and how this miscarriage of justice occurred in her new novel, The Fortune Men. It’s a searing indictment of the British Establishment of the time, but also an affectionate and highly detailed portrayal of the Cardiff Docks and its tight knit, sometimes fractious, sometimes protective community of Welsh, Somali, West African, Caribbean, Indian, Maltese and Jewish residents. A busy port of the British Empire, built on the export of South Wales coal, with representatives of every corner of that Empire—seamen, refugees, immigrants, and a local working class all living and co-existing cheek by jowl.

The Somali community in Cardiff was composed mostly of sailors who, when their ships docked, chose either to sojourn for a while in the city or stay for good. Mattan, a merchant seaman, had passed through the port several times and on one shore leave had fallen in love with a local girl called Laura Williams and decided to stay and put down roots. They had children, but the marriage didn’t last due, it seems, to Mattan’s gambling and debts. Mohamed’s picture of Mattan is not of a particularly bad man—neither a violent drunk or an abuser—but perhaps one who skirted the law a little when short of cash and, crucially in terms of the way he was to be treated by the organs of the British state, insistent that he be treated as man equal to any other in Cardiff. This was to earn him a reputation with the local police and those who disliked him as ‘an uppity’ Somali, ‘cheeky’, not ‘knowing his place’ as the police saw it. This refusal by Mattan to willingly subjugate himself to authority, to demand equal respect, was to mark him in the eyes of the local constabulary.

Mohamed is keen to highlight that Tiger Bay was part red light district, part poor working class area, and subject to all the problems of places without much money and with a transient population coming and going. However, the murder of popular local Jewish shopkeeper Lily Volpert, who ran a general outfitter’s shop that sold seemingly anything and everything under the sun at prices locals could afford, was atypical and extremely shocking for the area. The police wanted to solve the vicious murder fast. There were rumours a black man had been seen in the area just before the murder in the doorway of Lily’s shop. Mattan, known to the police for some minor crimes, was an easy ‘fit up’. Rewards were offered for information and some it seems didn’t care too much about the veracity of their tips if the reward was forthcoming. The local Somali community raised funds for Mattan’s defence. Some spoke up for him. But others, as Mohamed shows in her reconstruction of the swift trial, blatantly lied, while other leads, sightings and suspects were not followed up and allowed to leave the country.

Mohamed’s Mattan is not a simple character. He does not initially help himself by belittling himself. Where others might seek to ingratiate themselves with the police and court Mattan stands defiant, certain of his innocence and that the truth will out. It is a misplaced certainty at odds with the rigged system that seems determined to prosecute him. Mohamed’s slow build to Mattan’s realisation that he is perceived as guilty, that he is caught in a system that is prejudiced against him, and that unreliable witnesses are testifying against him and being believed with little cross questioning, is devastating.

Nadifa Mohamed’s previous work has been highly praised. Her first novel Black Mamba Boy (2010) was a semi-biographical account of her father’s life in colonial Yemen in the 1930s and 1940s. It won a lot of awards as did her follow up, the 2013 The Orchard of Lost Souls, set in Somalia on the eve of the civil war in 1990. Mohamed’s father was a sailor in the merchant navy and brought his family to London in the mid-1980s when his daughter was just four. When the Somalian Civil War broke out a few years later the family stayed along with many other Somali families and refugees from the fighting. During his time as a sailor before the Second World War Mohamed’s father had met Mahmood Mattan in the north-east English port city of Hull. Later, his trial and execution was to light up the Somali merchant sailor grapevine around the world. Nadifa heard the story from her father. It stuck in her mind. She began to research it and found herself deeply embedded in the crime genre for the first time.

The Fortune Men then forms a bridge in the British-Somali experience and collective memory between the earlier generation of Somalis, many of whom arrived before, during and just after the First World War in British port cities like London, Liverpool and Cardiff, and the later generations that came in the 1990s after the civil war broke out. That earlier generation saw prejudice in jobs, housing and justice as well as severe “race riots” in many British cities, including Cardiff, just after World War One.

The novel is a highly detailed reconstruction of the case, and Mohamed is keen to say that she built upon the non-fiction research and reconstruction in Chris Phillips’s 2020 self-published book Hanged for the Word If. What elevates Mohamed’s novel for admirers of high quality literary crime is her attention to detail. The look and feel of the streets of the old Tiger Bay, the generally poor but honest families that lived there; the sense of community and how it could both band together to protect itself yet also fall out and come into conflict over petty differences. Mohamed admits that in some cases—with both Mattan and some of the characters that swirled around his case—she has had to imagine their back stories. However, they are believable and historically justifiable and, when combined, present a portrait of the human elements of the sinews of the British Empire that brought men and women of varied class, race, and religious backgrounds from around the world to the damp back streets of Cardiff. This is strong, vivid writing with an incredible sense of place.

A sense of place and world that is all the more amazing now that Tiger Bay is long gone—demolished in the rush of post-war clearances. Mohamed believes the areas was “cleansed”, being seen as a “blemish” on Cardiff in the intolerant 1960s and 1970s. Yet here once lived a vibrant community with tales to tell—Nadifa Mohamed has recovered one of the most difficult yet vitally important memories.