I have a confession. Long before I became a cozy mystery author, I had a dream publishing job as a Nancy Drew editor. But to be honest, I didn’t always love the famous girl detective. Not as much as her legions of fans, anyway. To me, her character was too…perfect.

I’m not a Nancy Drew expert. Sure, I enjoyed reading her adventures, in early editions passed down by family members and 70s-era volumes off my summer camp bookshelf. But in the late 80s/early 90s, sharing an office with my Hardy Boys counterpart, I managed two Nancy series: the traditional Nancy Drew Mystery Stories and the Nancy Drew Notebooks. Oh, and River Heights, a YA spinoff more akin to Sweet Valley High, in which Nancy made regular cameos. (I also edited my childhood Stratemeyer favorite, The Bobbsey Twins.) My employer, a children’s book packager, hired freelance writers and artists on a strictly anonymous, flat-fee basis. Each stage of the creative process—story thumbnail, synopsis, outline, first and final drafts, back copy, cover art—was approved by both the licensor—the Stratemeyer Syndicate—and the publisher. Two editors handled the Stratemeyer series on the publisher’s end as well, but the expectation was that we would deliver final books.

Due to the huge popularity of Nancy Drew at the time, production schedules were tight, much as they’d been in the early Stratemeyer days. If a development stage was delayed, we borrowed time from the next—or risked missing our pub date.

If a cover painting arrived at our office that wasn’t quite right (say, Frank and Joe Hardy reacting to an explosion from the wrong direction), there was little window to fix it. The artists were busy painting covers for publishers all over the city, and the oil paint on the canvases was often delivered damp. Luckily, one of our authors was also an artist. He showed up with his own paints and touched up the canvases as fans blew behind him.

But when a plot snarled or a manuscript didn’t have the correct “voice,” we editors went to Defcon Drew. If an outline or entire draft needed to be “recast,” as we euphemistically termed it, we hired rewriters to turn the work on a dime. If none were available, we were the last line of defense, doing the recasting ourselves. To keep our energy and spirits up, our bosses plied us with chocolate, soda, and popcorn—but not pizza because the grease made us groggy. Nancy and her team would sleep when they were dead.

But Nancy was immortal.

While the girl detective was brazen and even unruly in her earliest adventures, thanks to ghostwriter Mildred Wirt Benson (aka Carolyn Keene), the red pencil (and later, typewriter) of Harriet Stratemeyer Adams later brought the stories—and Nancy herself—into line with the social mores of each decade. She also removed racist, sexist and other disturbing elements from the early editions, writing entire books if needed. In the “recasting” process she toned Nancy into the practical, unflappable young woman readers came to admire and love. Or, in my case, not love. I can’t say I ever told a New York Times reporter I was “so sick of Nancy Drew I could vomit,” as Millie Benson did, but I may have come close on occasion.

Nancy was ever predictable: smart, brave, talented, practical, confident, sophisticated, popular, and poised. Other than those of the criminal persuasion, everyone showered her with praise. Even her doting father, a brilliant attorney, treated her as a grownup. When, like most amateur sleuths, she stepped outside the lines, no one blinked. Plus she had a dog, Togo. Well, sometimes.

During my time in Nancy Land, the editorial directive was clear: Make Nancy more like a regular—though insanely gifted and privileged—teen. We gave her more interest in fashion, school activities, a social life, and even romance. She was an instant whiz in every art and sport. But the more we tried to make Nancy “normal,” the more she remained just beyond our reach.

I begged the editor-in-chief to let us shake Nancy up a little, throw her harder curve balls that weren’t investigation-related. Couldn’t she laugh more? Nancy wasn’t known for her humor. What if she actually ate those fattening donuts with Bess Marvin? Or really messed up on a regular basis, and had to deal with serious consequences?

The editor-in-chief explained, very gently, that I was out of my mind. Nancy’s personality needed to remain the same, even as the world changed around her. Her best chums, Bess and George, had bigger assignments than being helpmates or sounding boards—or conveniently twisting an ankle and falling into a well just as the bad guys closed in. If you meshed ’fraidy-cat Bess (who could talk a suspect to death faster than Flossie Bobbsey) and action hero George with Nancy’s neutral personality, you had a well-rounded, entertaining sleuth in one neatly tied package. Nancy’s less sharply defined personality allowed more readers to identify with her and co-solve crimes. Our job was to give them the Nancy they knew, every time, and keep the focus on her investigations.

Well, okay. But could we at least get rid of Nancy’s longtime boyfriend, the handsome, ever supportive, and deadly dull Ned Nickerson? Negative, although the couple repeatedly broke up and reconciled in the Nancy Drew Files. My colleagues didn’t care for Ned, either. Fueled by still more caffeine and sugar, we spun elaborate ways to dump the poor guy for good during group brainstorming sessions. Spoiler: none of our brilliant ideas ended up in any Nancy books.

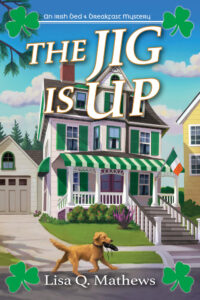

With time, though, I felt sorry for Perfect Nancy. All those rules, clearly listed in the series “bible” given out to authors, didn’t leave her much room to grow beyond her detective expertise. And as my cozy THE JIG IS UP debuts, I can’t help thinking of the highly similar rules cozy authors were once strongly encouraged to set for their sleuths, well beyond “no cursing or onstage sex or violence.” My sleuth Kate Buckley, a single mom, police chief’s daughter and tax accountant with two kids in Catholic school—plus a very challenging sister—knows all about rules, which she’s constantly forced to break. Luckily, rules have changed in Cozy World, with greater inclusivity, expanded family relationships, social issues, and much more. Freed from expectations of perfection, the new amateur sleuths, both teen and adult, have more options now. They can be themselves, make mistakes, and dollars to Bess’s donuts, they’ll find readers (and editors) who love them. They all share the dogged pursuit of truth, justice, and the mystery way.

Recently I tuned in to Nancy Drew, the TV reboot that ran four seasons during the pandemic on the CW. Darker than I’d imagined, with real supernatural elements rather than the ones Nancy always explained away with logic in her books, it was a change, for sure. Many Nancy book fans on Reddit were upset. I get that, I really do. But our less-perfect girl detective somehow seemed more real. And happy at last.

You go, Nancy Drew.

***