Crime fiction sometimes seems like a solo sport: one man or woman coming up against the forces of confusion and chaos and fighting through them to identify a solution. We start in disorder and end in (some version of) order. At least that was my assumption, before I read Chester Himes.

A native of Missouri, Himes spent his most productive years in France, where he began writing hardboiled detective fiction set in Harlem. In some ways, this was a practical decision—Himes had failed to find success writing screenplays and traditional literary fiction—but it also enabled him to explore a community that hadn’t been represented in crime fiction to that date. Like the other novels in the Harlem Detective series, A Rage in Harlem is full of outrageous characters and over-the-top situations, but also a strong and deeply felt sense of place.

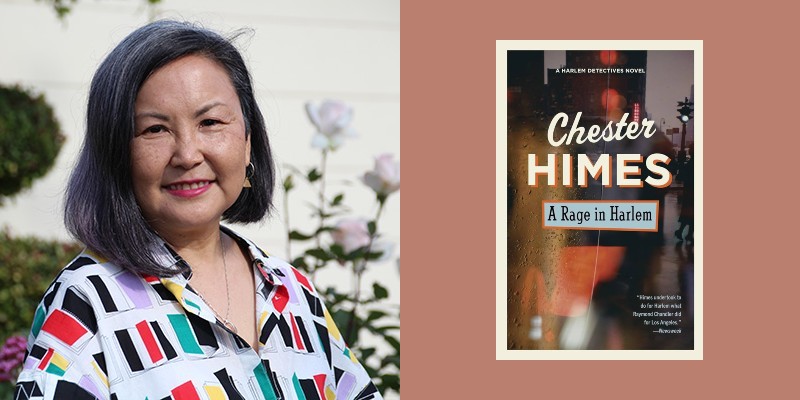

I can’t think of a better guide to Himes’s work than Naomi Hirahara, author of the Edgar Award-winning Mas Arai series and the Japantown Mystery Series, Clark and Division and Evergreen, as well as many other works. Like Himes’s, Hirahara’s work is grounded in the history and experience of a specific community, explored with love, humor, and understanding. In this crime fiction, solutions aren’t always apparent, and endings aren’t always tied up with a bow. The reader closes the novel with the sense that the characters will keep living their lives, in some parallel reality to our own.

Why did you choose A Rage in Harlem by Chester Himes?

When you asked me to do the interview, I thought, “What crime novel really helped me when I was writing my debut mystery?,” and A Rage in Harlem immediately came to mind. My first novel, which is called The Summer of the Big Bachi, actually didn’t start off as a mystery. I was writing it very intuitively, and then I came across A Rage in Harlem. There was something about it that was so pungent and so freeing, and I really needed that. My first novel is about a gardener in a very isolated community, the Japanese American community in southern California, and something about how Chester Himes wrote about community just resonated with me. A lot of classic crime writers like Raymond Chandler have that lone investigator moving through a dark world and trying to root out the evil on their own, but I liked that Chester Himes was writing about lots of people. There was a connection there, and it enabled me to write with more abandon. I don’t necessarily have the same style of humor that he has, but I appreciated the characters so much. They all had different motives, they were all incredibly flawed, but you still rooted for them, and that’s something that I wanted to incorporate in my own work.

I’m really interested in the two adjectives you used to describe A Rage in Harlem: pungent and freeing. Could you talk a little bit more about that?

In that Mas Arai series, which spans seven books, I was going for something that smelled really strong. Sometimes when we write we think more in terms of our vision or hearing, but to me, to get a true kind of sensory personality of a place and a people, I think you need that pungency. I appreciate that kind of writing that’s beautifully constructed, like it was made by a Swiss clockmaker, but I also like something that doesn’t necessarily have that same kind of preciseness or maybe laboriousness. In that first book, I needed to just trust myself, because I didn’t really know what I was doing in terms of craft. I needed to remember that we’re all storytellers in our regular lives, and I had to lean on that.

The novel opens in the point of view of a man named Jackson, living in Harlem in the forties with his girlfriend Imabelle. Jackson has found a man who promises to “raise” his ten-dollar bills into hundred-dollar bills through a chemical process activated by heat, but when they try it, the oven blows up and a man claiming to be a U.S. marshal bursts into Jackson’s apartment. It’s only the beginning of a tale of bad luck and near-misses where the only constant is Jackson’s naivete and his steadfast love for Imabelle. What did you think of him as a main character?

I really love Jackson. In my own writing, I tend to gravitate toward the every-person, or maybe even the antihero. Death of a Salesman made a big impact on me, because Miller selects a character who seems perfectly average, or maybe even below average, and finds a way to shape that life so it can interest a person who is very much outside of that lived experience. If you look at Jackson, he’s really the purest character in the whole book. Even the minister has ulterior motives.

Jackson is just such a human character to me. He’s looking for money all through the novel, and he’s finally able to amass this money that he can pay off his debts and get out of trouble. But then he goes to the craps table and loses it all. We all do things from time to time knowing that we shouldn’t go there, we shouldn’t do that, but we’re somehow ensnared by the possibilities. A lot of crime and mystery writing is about people making those kinds of bad decisions, so I’m actually very much enchanted by Jackson.

Jackson believes in Imabelle implicitly, but the reader soon becomes aware that she’s teamed up with a group of men to double-cross him. Imabelle is clearly an opportunist, but given the world she lives in, one can hardly blame her for looking out for herself. Do you think Himes expects the reader to sympathize with her?

I sympathize with her. I mean, she’s definitely conniving, but I think Himes is sympathetic to women in general. In his personal life, when he couldn’t make it in the US and went off to France, it was a woman editor that gave him the idea to start writing crime fiction. It wasn’t necessarily a genre that he had in his heart. To be perfectly honest, he started to write these New York novels for commercial reasons.

With Imabelle, I think he wants to give us a sense of the violence and subjugation that a woman like this would have lived in. The options were just so limited in terms of what a young woman could do to survive, and I appreciate her wiles. And then there’s the fact that Jackson adores her so much. For a writer, that’s a technique that’s kind of handy: if you have a character that isn’t immediately likable, but then you have a very sympathetic character that is totally devoted to him or her, that can make you feel more positively toward them. If Jackson’s going to adore her so much, we’re going to root for her as well.

One of the most interesting characters is Jackson’s twin brother Goldy, a heroin addict who spends most of his time dressed as a nun, selling tickets to heaven to Harlemites. Goldy is part of a community of what the book calls “female impersonators.” It’s not clear from the text whether they’re transgender or simply making a living as best they can, but it suggests a flexible attitude toward gender that might seem surprising given the time. What did you think of Goldy as a character?

I love Goldy. I’m sure he’s probably everyone’s favorite character who encounters this book. I think what Goldy represents—what is true of so many of these characters—is this idea that what you see is not really what you get. In a sense they all have secret identities, and here’s Goldie pretending he’s a nun. It’s a little bit absurd, and even though that’s not part of my style, I appreciate it in other writers.

The descriptions of the setting were one of my favorite parts of the book. The novel abounds in great, heartbreaking details, like the giant dogs kept by pimps in apartments so small that the dogs need to be chained at all times. Himes clearly knew this neighborhood inside and out and loved writing about it. What did you think of that aspect, and how do you think about setting in your work?

I think that’s so important. When outsiders think of Harlem at that time, they might think of nefarious activities, but the book is really about connections between people: family connections, romance, love. In spite of all the crime that takes place in the novel, he also wants to get into the essence of human experience in terms of those connections, and that’s what I want to do in my books as well. I’m exploring the erasure of people of color from history, specifically Japanese Americans. In Clark and Division, the characters are forced to leave their home in southern California and move into a camp, and then they have to move again. I like giving characters life in those kinds of situations, so you can see that these were real people and not just figures in a history book. Like Jackson in A Rage in Harlem, they’re looking for love, they’re looking for a better future. They have aspirations, even though they’re taking place against this background of criminal behavior.

Those kinds of locations are very intriguing to me. Some of that may be personal—I’ve ended up writing a lot about gambling dens, and my father loved to play poker in the back of gas stations and to go to Vegas. I’m not necessarily a gambler myself, but I like being around the fringes and watching people and their excitement. There’s constant action in that kind of setting that is also present in A Rage in Harlem.

The the detectives who play a minor role in this novel, Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson, are more central characters in the other novels in the series. Have you read any of the later novels?

I have, but I have to say A Rage in Harlem is my favorite. The names Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson give you a clue about what kind of law enforcement they are, and you’re not quite sure if you’re rooting for them all the time. Because Jackson is the center of A Rage in Harlem and has that innocence and purity, it just appeals to me the most.

Without giving any spoilers, you could say that this novel has a kind of circular structure, and we end with the impression that things are going to go on very much as they were. What do you think Himes was trying to say with the ending?

It’s interesting, because it’s so different than a middle-class or even an immigrant view of the world. In those communities, people tend to believe that things are going to progressively get better, but In Jackson’s community, things are just going to stay on pretty much the same. It says something about the strength and the durability of the characters that in spite of this cycle they can live life with such as zest. They don’t give up, and they’re not passive. And I think that’s the beauty of our genre too. Crime fiction requires motion; the characters can’t just stay frozen in trauma. They have agency, and sometimes that means making the wrong decision. With Imabelle, she’s frightened and scared at the end of the book, but she still seems like a woman to contend with. She commands respect in her world, and I like that.

Is there anything else you’ve learned from this novel that you might apply to your own work?

I’d say that Chester Himes is always present in my work. He actually wrote his first novel in the home of a Japanese American woman journalist who rented the house to him when she was sent to a camp during World War II. When I found that out, I felt like there was a real connection between us.