Oliver Stone’s mesmerizingly gaudy tale of criminal lovers Mickey and Mallory Knox carving a trail of death and destruction across America’s arid Southwest, became a cause célèbre, upon release in August 1994. In the US, Great Britain and France, the press played armchair shrinks, attempting to blame Natural Born Killers for a spate of homicides in their respective nations. All veritable nonsense of course, but since when did that stop the news media (ironically, one of the film’s many satirical points).

As much as it is a candy lane of murder and mayhem; Natural Born Killers is a world away from 1980s action movies and their bombastic carnage. In the early 1990s, one man (Quentin Tarantino) and his reservoir dogs, in the slice of a cop’s ear, refashioned film violence as sadistic, cruel, and anti-authoritarian. He had shaken the audience out of their drunken and accepting stupor. Kind of. He wasn’t being moralistic; he had always found cinematic bloodshed exhilarating. Some audience members and some critics were disturbed by his film’s casual and gleeful torturing of a LAPD patrolman set to a pop ditty (Stuck in the Middle with You, by Stealers Wheel), but in general here was a man who’d turned the video store film geek figure and film geek culture into a dominant force to be reckoned with. Such was Tarantino-mania (especially after 1994’s Pulp Fiction) he was treated more like a rock star than a movie director.

With Reservoir Dogs (1992) changing the zeitgeist, never mind defining it, Hollywood studios suddenly (luckily) remembered they had on their hands two unproduced scripts penned by the hotshot. Striking while the iron was hot, those two scripts dusted off and quickly turned into movies were: True Romance and Natural Born Killers. One, released in 1993, helmed by Tony Scott, met Tarantino’s approval. The other, made by Oliver Stone, did not.

Having caused his own kerfuffle with his magnum opus JFK (1991), an exquisitely made paranoiac’s view of mid-20th century American history, the iconoclastic rebel and Vietnam vet this time had a project based on a script by the guy who’d become a one-man cultural phenomenon. Both True Romance and Natural Born Killers incorporated two quintessentially American genres: the road movie and the lovers-on-the-run crime flick. Both took a direct cue from Terrence Malick’s 1973 debut, Badlands (itself inspired by the real-life homicides committed by Charles Starkweather and his accomplice Caril Ann Fugate, in the 1950s). But the difference between True Romance and Natural Born Killers is night and day. True Romance is goofy and romantic and in a closer vein to Tarantino’s oeuvre, while Natural Born Killers in Stone’s hands became something fierce and scalding.

Tarantino received a Story By credit on the latter, despite being the originator of the screenplay. Oliver Stone and his co-writers (Richard Rutowski and David Veloz) reworked it, keeping much of the dialogue intact (to maintain that crucial QT flavour), but chopping and changing enough to earn his ire. In 2007, on the Opie and Anthony radio show, Tarantino was asked what it was about Stone’s film he did not like. He replied: ‘First and foremost, they re-wrote my script, so you can stop right there.’ He simply did not take kindly to having his script tampered with. It was a creative ego thing. A comparison between the scripts reveals lots of chops and changes, shifts in emphasis (the TV documentarian Wayne Gale has a larger role in the original script), but it’s not a butcher job, far from it, and the basic structure remains.

If JFK provided a talking point about American historical amnesia and secret histories, Natural Born Killers gave Oliver Stone fresh opportunity to dissect another of his homeland’s clear and present dangers: vampiric news media sensationalism and the predilection for creating icons and myths out of criminal activity. Stone’s America is forever a haunted landscape painted in the blood of others. His best work – Salvador (1986), Platoon (1987), JFK, Natural Born Killers – is all about ripping off the Band-Aid and picking at the scab. None of this is what the essentially apolitical Tarantino had in mind when he attempted to get his own version of the film off the ground in the late 1980s, before selling it on to producer Don Murphy, who later sold it to Warner Bros.

For Tarantino, his films in this era were about nothing more than adoration of genre movies. To Stone, Natural Born Killers would become a sermon delivered from the pulpit and, somewhat transgressively, he made Mickey and Mallory’s story more romantic. Stone’s film is a carnival of the grotesque, a three-ring circus of chaos, a death-trip into the heart of American darkness, but at the centre of the maelstrom is the shining light of love.

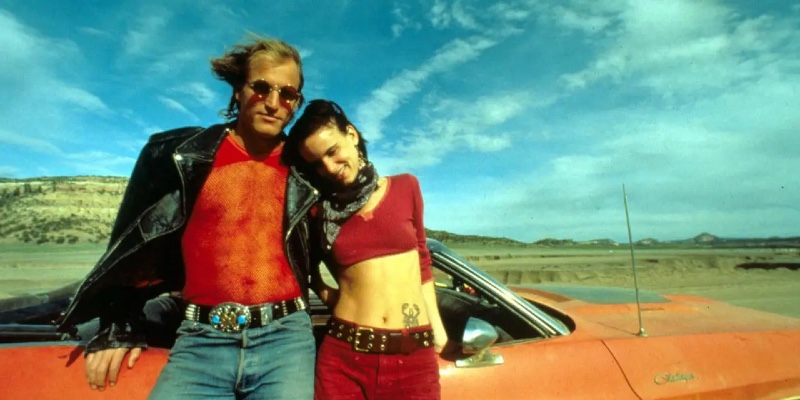

For all the diatribes and barbs thrown at newspapers and news channels, and the hypocritical consumerist society, Natural Born Killers is a powerful love story. Hidden inside the transgression is something potently optimistic. Written off in life as dumb white trash, Mickey and Mallory Knox (played by Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis) are connected spiritually on a profound level, they complete a union of the masculine and the feminine, they are each other’s salvation. Yes they are lethal killers, but they are equally the purest and freest people in the entire film. ‘Love kills the demon,’ Mickey says in his jail cell interview before the prison riot commences in the film’s climax. And he isn’t wrong. Stone further emphasised this poetic introspection by using Leonard Cohen’s tracks Waiting for the Miracle (opening credits sequence), Anthem (during the prison break sequence), and The Future (over the end credits). They all present dark visions of the world but with hopeful lyrics mixed in. If the latter warned us, ‘get ready for the future, baby, it is murder,’ it reminded us too that ‘love’s the only engine of survival’. The trick in Natural Born Killers is to be simultaneously optimistic as it is bleak.

30 years on, Natural Born Killers remains a benchmark of 1990s American cinema; conflicted and conflicting, contradictory, mad, bad and wilfully gonzo, but it is bravura filmmaking all the way; an aesthetic tour de force of film stocks, expressionist editing, anarchic set-pieces revelling in artifice, presented in music video visuals and soundtracked by an eclectic compilation of gangster rap, industrial metal, the Cowboy Junkies, Bob Dylan, Duane Eddy and Patsy Cline, put together by Trent Reznor, of Nine Inch Nails. But it would all be empty in effect if we didn’t wish Mickey and Mallory some luck in their bid for freedom against the sick society which damaged them. They captivate us ultimately, not through depraved and maniacal acts of violence, but their consuming passion.