My life has always been tied to the natural world. I was raised on a thirty-eight-acre parcel of land that, though no longer in my family, still bears my family’s name: the Langsfeld tract.

The house I grew up in, designed and built by my parents in the early 90s, sat at end of a two-and-a-half-mile road dirt road that was built specifically to get our house. Our nearest neighbor was a mile away “as the crow flies,” and our property butted up against the 1.7-million-acre Gunnison National Forest.

As a kid, my parents would tell me and my siblings to “go play outside.” For some this could mean “go throw a ball in the yard” or “ride your bike around the neighborhood.” To us, “outside” contained multitudes.

We had dirtbikes we rode on the two and a half miles of track we built ourselves on the property. A few hundred yards from the house was a ravine with a seasonal creek that ran through its gut. I’d spend hours there in the summer, damming the creek and digging pools or building lean-to forts out of sticks propped against logs.

Once we devised a form of tag where you weren’t allowed to touch the ground, instead running and leaping along the downed trees that littered the drainage. How none of us came out of that era with any broken limbs is anyone’s guess.

Behind the house we had a permanent camp set up where we’d have barbecues and campfires in the summer. For us, “Go play outside” could mean “go climb a mountain,” and there were two mountains we could climb by simply walking out our door and striking off in their general direction.

As an adult I’m still drawn to the outdoors. Whether I’m trail running, hiking, skiing, hunting, or camping, these are all different forms of the same thing. In Japan they call it shinrin-yoku or forest bathing. In Norway it is friluftsliv, open air or outdoor life. In the mountains I find a healing of the spirit that humans across cultures have known about through all of history.

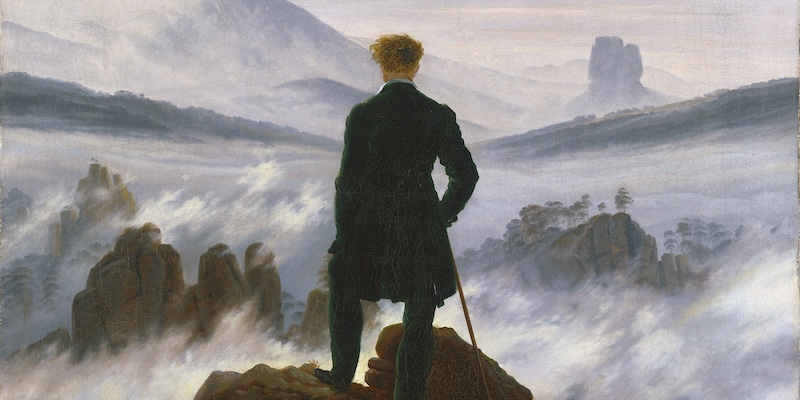

In my debut novel, Salvation, the main character, Tom Horak, finds solace and redemption in the stark beauty of the Rocky Mountain wilds after committing a horrific murder. Much like myself, the quiet of the mountains, away from the civilized world, are a place where Tom can let go of everything the outside world has thrown at him and be completely himself. It’s a place to tap into a sense of the divine and simply exist.

For me as for Tom, it is not just the beauty of the landscape, but the ambivalence of nature that provides the perspective needed to feel human and take responsibility for our actions. In the solitude of wild lands, we can see ourselves as we truly are: flawed humans making our way through a complicated world.

Mother nature is neither cruel nor kind. It’s the sort of benevolent god that created the world then stood back and watched it all play out according to a set of semi-undefined rules. It is the acceptance of our place in that world, within those rules, that humankind can find a sense of balance and belonging.

Years ago I went for a trail run into a wilderness area just north of my hometown. After climbing out of the trailhead for a mile and a half, I crested a pass and dropped into a broad mountain valley carpeted in one of the largest stands of aspen trees in the world. As I ran along the trail through the woods, I began to hear the high-pitched squeals of elk calling to one another.

The trail I followed wound out along a large bench sandwiched between the bald south side of granite peaks and a deep ravine that is the head of a canyon. As I came to the edge of the woods, where the trees faded and a long grassy field perforated by a small group of spruce and firs stretched out before me, I tracked to the right and up the base of the mountain.

From that vantage I could see the elk herd grazing in the morning light. A group of cows and calves, the calves still speckled along their backs as they are in the first few months of life. This was early to mid-June, and elk in Colorado typically give birth in May and June, so these could only be weeks old, at most. I sat for a while as the elk grazed away from me, beyond the bench and into a drainage to the west.

This was a strange time in my life. I was young, in my early twenties. I’d settled back in my hometown after a four-year hiatus and was working jobs I didn’t necessarily enjoy but that allowed me the freedom to shape my days.

I spent much of my time in the mountains, mostly rambling, an aimless wandering that mirrored the direction of my life at that time. This was a place I’d been many times and knew well, yet I had no idea that it was an elk calving ground. Where I grew up, calving grounds are not a place that you go during calving season if you have any sort of respect for the animals that find refuge there. In the moment, it was a place that felt secret and sacred, and I was the intruder.

This was a strange feeling for me. The mountains had always been my home and I had always felt comfortable there. Yet here I was, clearly an outsider, clearly not of this place. It was not unlike how I felt about life in general at that point.

In retrospect I was searching, somewhat haphazardly, for direction or meaning. The bulk of my twenties can be summed up as coming back to my hometown, getting a job and saving up some money, then buying a one-way ticket to Latin America and bumming around until my money ran out. Then I’d fly home, find another job, and do it all over again.

It was that strange time in life, that maybe a lot of people go through, when I was reckoning with aspects of my childhood that still brought me discomfort while trying to find my own adult identity; two versions of myself that are not so different from one another as I once thought. It was like simultaneously running away from and toward the same thing.

Through that time, it was the wild lands that kept me grounded. To folks who know me, it should come as no surprise that I leaned heavily on this aspect of my identity in writing Salvation.

I’ve had less trauma in my life than many, perhaps more than others, but that’s exactly the point. Nature just is and allows us to just be, regardless of background or how we’ve lived our lives. It’s a place one can shed their skin and find redemption, solace, and healing. That’s a reoccurring experience I need in my life and the reason I live where I do, in a small town surrounded by broad expanses of wilderness.

Life is guaranteed to throw all sorts of the unexpected our way, good and bad, whether we are prepared for it or not, but when you’re out there, alone in the woods, none of that matters. Your days are free and the simple beauty of existence stares silently back at you from every hidden creek bed and across every broad horizon.

***