Whatever drew me to set a crime novel in Paterson, New Jersey? That’s a question I’ve been asked more than a few times, and one I’ve occasionally considered on my own. It’s a lot about family history and personal meaning (the city is where I was born), but that was never the entire pull. When I began taking those very first steps towards writing in a new genre and crafting a 1970s police procedural, I looked for a setting that felt natural for the kind of crime fiction that interests me most – a little gritty and very real-life. Paterson is urban, but not necessarily impersonal or alienating in the way that New York and Los Angeles are often rendered in novels, and more the kind of city a police officer can patrol and see the same handful of people every day. With a cityscape that included a traditional chrome diner called “The Egg Platter” for seven decades, it’s exactly the place to bring a reader on a colorful, police-style ride along.

Perhaps more than other genres, crime fiction demands a granular level of detail and intimacy in setting. From beginning to end, cops are traversing the streets, in cars and on foot, looking around and unearthing the large and the small. Settling in with a crime novel, a reader can expect to be brought into a city like Paterson and come to know it well. To write historical fiction, historical crime fiction, is to be tasked with creating everyday moments and bringing a world of specificity to the reader.

What would a reader see of 1970s Paterson on a police ride along – real or imagined? It might have looked like a basic rust belt city, with its downtown a mix of landmark buildings and potholed streets. But then again, Paterson has always been a unique urban landscape, centered around the Great Falls of the Passaic River – a 77-foot drop of rushing water smack within the city limits. The mills that circle the Falls tell the story of Paterson’s place as the country’s first planned manufacturing city and its once vibrant silk industry. The entire design was conceived and then created by Alexander Hamilton. As of the late 1970s, the mills had begun to empty and in the present day, they appear nearly gothic. Those visual and historic details seemed compelling and necessary to my novel’s setting, while at the same time they threatened to interfere with the essentials of time and place that are vital to driving plot.

I wasn’t writing a book about the failed textile industry or about a murder that took place in an abandoned mill, yet the texture of the old industrial sites and their surrounding neighborhoods was leeching into the novel. As often happens with an overload of information, I’d become a little lost turning over what setting could do for the story and what I wanted to bring to the page. Somehow, I found my footing in Nordic Noir.

Crime fiction from the far north, that colossus of a genre, tends to be described with words and phrases like “bleak” and “foreboding” and “endless night.” The setup is one of long and hard winters and the propensity for violence. The locations are pretty dark and pretty cold. The crimes, espresso-strength black. But, as has been known for years, there’s so much more to the genre. For my writing journey, it was the use of setting as a means to plumb large social issues that led me back to Paterson.

I’d begun my Scandinavian-based reading a few years earlier, bingeing through Jussi Adler-Olsen’s Department Q series, then onto Jo Nesbø, Henning Mankel and Ragnar Jónasson. And when I looped back to Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö (though, arguably, that’s where I should have started), it all just fell into place.

Using profoundly spare prose and classic grounded-in-reality police procedurals as their lens, the pair’s novels (a series of ten) questioned how pornography, child sexual abuse, rape and mass murder could ever co-exist with a supposedly evolved Swedish society, and shaped crime fiction forever. Credited with creating the genre, Sjöwall and Wahlöö did so with a light touch – never straying from the procedural structure, while simultaneously expanding its possibilities and deftly included all levels of social commentary. Because the crime fiction that followed was always about the struggles plaguing society and how specific environments impacted both perpetrators and victims, the stories were always about place. Whether in Martin Beck’s Stockholm or Wallander’s Ystad or Department Q’s Copenhagen, we’re following a homicide detective gathering clues to solve crimes, and along the way, we’re also given glimpse after glimpse of the society at issue.

In a police procedural or a detective novel or a cozy mystery, an investigation will bring the reader deep within a town or a city. The setup almost inevitably fuels an understanding of the people who live there, and the social norms that drive them, and can also introduce the city itself as a character. Nordic Noir isn’t the sole place where that attention to setting is found, though that’s what the genre is widely known for, with Sjöwall and Wahlöö the standard bearers.

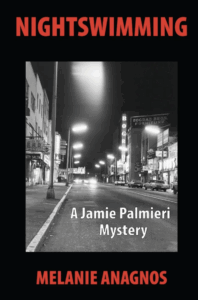

Painting location with a broader brush was what I decided to go with, not only taking readers to Paterson, NJ, but to the changing cultural landscape of the late 1970s. Nightswimming is a police procedural that’s a full-on murder mystery, also threading in some of the decades social and economic disruptions. The famous movements – civil rights and second wave feminism – were national and their impact well known. The dismantling of Paterson’s textile industry was local and deeply felt and affected both the people whose lives were splintering and the police who were called upon to unspool their crimes. It seemed the novel demanded that story.

***