‘A traumatised person does not remember the trauma, but experiences it over and over again,’ writes the author and psychologist Paul Verhaege. The past is alive, and it takes its toll.

Many years ago, we paid a visit to Jim Swire and his wife in their lovely, rambling house, which was full of comfortable clutter; there were family photos on the walls and a smell of baking in the kitchen. Our daughters played with their two dogs in the sun-drenched garden, among fruit trees and flowering shrubs. Jim Swire was a practising GP then; he was also, and very famously, a campaigner. In 1988, over a decade previously, his 23-year-old daughter Flora had been on the Pan Am Flight 103 to the US; the plane had a bomb on board, and it crashed in Lockerbie, Scotland, killing all its passengers.

What do you do when a beloved child is killed; how do you survive your grief? When we met Jim Swire (one of us, Nicci, was there to interview him), it felt to both of us that he was keeping the full knowledge of Flora’s death at bay by his tireless, relentless, unending campaign to find the people who were guilty. He was impassioned, fierce, dry-eyed and urgent – it was almost as if he felt he could still rescue her. His wife, Jane, on the other hand, was soft and worn with accepted sorrow, which seemed folded into her. As Bessel van der Kolk argues in The Body Keeps the Score, traumas inscribe themselves on a primal part of the brain, become embedded in the self. That visit was a quarter of a century ago. Every so often, we would read stories about Jim Swire in the papers: he was still campaigning; he would never stop, and perhaps by now he couldn’t. For if he did, it would mean accepting that the catastrophe he was seeking to avert had already happened, and what would become of him then?

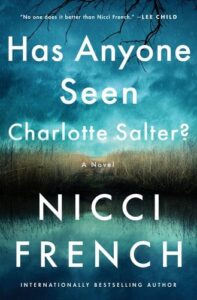

We didn’t leave the Swire’s house thinking we would write a thriller about the long term effects of trauma, yet the powerful impression of how differently and often unexpectedly people react to intense grief remained with us. We talked about it often. A great shock happens, a sink hole opens up in a family, say, and each person is affected in unique ways. In Has Anyone Seen Charlotte Salter?, four siblings, in their teens and early twenties, have their lives upended when their mother vanishes, as if into thin air. And she doesn’t come back. Her children are cast into a state of perpetual uncertainty, of agonised waiting. How do you mourn someone and heal if you don’t even know they are dead?

This is our twenty-fifth thriller. Almost all of our previous books take place over short periods of time: weeks, days, in one case (Losing You), a handful of hours, the same time as it takes to read it. In those, trauma is quick and sharp: a shocking event happens and it’s like a flash of lightning over the landscape. With Has Anyone Seen Charlotte Salter? we wanted to do something very different, and explore the effects of life-long trauma upon a group of characters. The novel opens on a winter night in 1990, at the fiftieth birthday party of Alex Salter. His wife, Charlotte Salter, does not turn up. Bewilderment turns to anxiety, and then to terror. The first section of the novel ends as a botched and incompetent police investigation runs into the ground.

Jump cut forward thirty years, when the four children return to their childhood home and we can see what the years of have done to them and how their mother’s unsolved disappearance has blighted their lives. The eager and hopeful young people are now middle-aged and they are all damaged in their own particular way. And they are still waiting, still in thrall to the past and haunted by their mother, who is like a radiant ghost in the novel.

Of course, Has Anyone Seen Charlotte Salter? is a psychological thriller: in the end, not knowing will be replaced by knowing. There will be a solution. When the family’s reunion triggers another violent death, the stubborn and clear-headed Detective Maud O’Connor arrives to lay a healing hand on chaos and grief. One of the great satisfactions of thrillers is that they can give a narrative structure and meaning to the mess of most lives. They are therapeutic in the way they often deal with rupture and repair. We have always wanted to write about the victims of crime, not the perpetrators: how ordinary people are affected by extraordinary events; how a life can unravel in a matter of moments; how we are all precarious and just a few steps from disaster. For the Salter family, the disaster is not sudden, but plays itself out in terrible slow motion. The Salters will find out what happened to their mother, but they will still be motherless. Crimes can be solved; life is another matter.

***