Nicholas Blake liked a puzzle plot as much as the next guy, and he was very good at constructing them: the dramatic murder, the enigmatic clues, the shifting suspicions as the spotlight shone first on one suspect and then another and then another, the final unveiling.

However, it wasn’t the puzzles that most interested him, nor the physical clues. It was the human mind. He was fascinated with the psychology that produced a murderer, or a victim—the why more than the how. In elegant prose, often touched with humor, his twenty novels between 1935 and 1968 explored many dark passageways about the pressures—physical, mental, social—that caused such crimes; the moral passions and human weaknesses that led people astray. He is often credited as one of the writers responsible for turning the detective story into the detective novel. The novelist Elizabeth Bowen described his books as “something quite by themselves in English detective fiction.” The New Yorker praised him as “an extremely accomplished novelist with the rare ability to understand people whose psyches are a mess and, at the same time, to write about them without ever losing his own balance or lightness of touch.” His books were an instant hit.

Nicholas Blake, however, was also just as notable for what he was not as for what he was. He was not the Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom from 1968 to 1972. He was not a Commander of the British Empire. He was not a professor at Oxford and Harvard, and a director and senior editor of one of Britain’s most distinguished publishing houses. He was not the person T. E. Lawrence once described as “the one great man in England.” He was not the father of one of the greatest actors of our time.

All of those people were Cecil Day-Lewis. But at the age of 30, Day-Lewis was a much-praised but struggling poet; a married man and father in dire need of one hundred pounds to repair his family’s cottage roof in Cheltenham; and a schoolmaster tenuously positioned at a public school where his leftist politics were increasingly frowned upon. In a letter to his fellow poet Stephen Spender, he confided, “I’ve been trying to write commercial prose, as I may get chucked out of my job any time now for my political opinions.”

And so was born an amateur detective named Nigel Strangeways, a well-born man with an acute sense of the inequality of the class divisions, and the nephew of an assistant commissioner of Scotland Yard, which gave him access and credentials.

In one of Blake’s early novels, The Beast Must Die (1938), Strangeways is described by a man sizing him up this way: “He saw a tall, angular young man in the early thirties, his clothes and his tow-coloured hair untidy and giving him the appearance of having just woken up from uneasy slumber on a seat in a railway waiting-room. His face was pale and a little flabby, but its curiously immature features were contradicted by the intelligence of the light-blue eyes, which gazed at him with disturbing fixity and gave the impression of reserving their judgment on every subject under the sun. There was something about Nigel Strangeway’s manner, too—polite, solicitous, almost protective—which struck Felix for a moment as unaccountably sinister: it might have been the attitude of a scientist towards the subject of an experiment, he thought; interested and solicitous, but beneath that inhumanly objective: Nigel was the rare kind of man who would not have the slightest compunction about proving himself wrong.”

In the very first book, A Question of Proof (1935), Strangeways is also burdened with several eccentricities. He is disheveled, short-sighted, walks with awkward movements, drinks far too much tea, sings loudly and badly, and sleeps under masses of blankets. These were all based upon Day-Lewis’s close friend and fellow poet W.H. Auden, whom he very much admired. Thankfully, Day-Lewis must have realized that these affectations were all unnecessary, some even a bit silly, and they quickly melted away in subsequent books.

In his lifetime, Day-Lewis was always wary that his work as Nicholas Blake might be taken by some critics as proof that he wasn’t sufficiently serious about being a poet, and indeed he did take some flak…And, in fact, that first novel almost did get him thrown out of his teaching job, but not because of his political views—he was a member of the Communist Party from 1935 to 1938 (MI5 even spied on him), but quickly became disillusioned after the Stalinist purges of the late ‘30s, and denounced the party, even though he remained a radical. No, it was because A Question of Proof was set in a public school much like the one in which Day-Lewis taught, and at which fictional school the headmaster’s wife was having it off with a young teacher. The chairman of governors of Day-Lewis’s actual school took profound umbrage at it all, was convinced that the affair was true, and it took a personal assurance from the actual headmaster’s wife that she was not romantically involved with young Mr. Day-Lewis to save him from getting fired.

This would hardly be the last time that Day-Lewis used his background and interests as fuel for his books. His time at Harvard was the setting for The Morning After Death (1966); his stint during World War II as a publications editor at the Ministry of Information became Strangeway’s wartime job as the head of the editorial unit, Ministry of Morale, Visual Propaganda Division, in Minute for Murder (1947); End of Chapter (1957) mined his experiences at the publisher Chatto & Windus; the protagonist of The Beast Must Die, consumed by his thirst for revenge on the hit-and-run driver who killed his young son, was inspired by a similar near-miss situation for Day-Lewis’s eldest boy, Sean; the tortured, blocked poet of Head of a Traveller (1949) who experiences a perverse creative resurgence after a grotesque nearby murder, was, many have thought, a reflection on Day-Lewis’s own poetic world; and Day-Lewis’s distrust of the establishment came to the fore in many different ways: In There’s Trouble Brewing (1937), for instance, the dead body belongs to a tyrannical brewery owner who refuses to modernize his plant, thus endangering his workers. In The Beast Must Die, the murderer confides to his diary that “only generals, Harley Street specialists, and mine-owners can get away with murder successfully.” In The Smiler with a Knife (1939), Strangeway’s wife, Georgia Cavendish, a renowned explorer and adventuress, agrees to go undercover to infiltrate a dangerous fascist group in England, but at the end refuses to accept the government’s “thanks of a grateful nation”:

“She did not wish to be reminded of [her ordeal] by the fulsome compliments of politicians whose own pusillanimity or self-interest were responsible for its having happened at all. She had performed her task and wanted no thanks for something which should never have been necessary.”

Article continues after advertisement

Georgia is a lovely character, fully her own woman, whom Strangeways met when she was a suspect in the death of her lover in Thou Shell of Death (1936), and whom often served as a sounding board for Strangeway’s musings during a case. She was loosely based on an older, sexually adventurous woman with whom Day-Lewis was entangled when at Oxford, to the distress of Day-Lewis’s vicar father. Alas, Georgia dies while serving as an ambulance driver in the blitz, an event dropped on the reader in three quick paragraphs in Minute for Murder. Day-Lewis’s son Sean, in his biography of his father, claims he got “bored” with her.

Her replacement, a talented sculptress named Clare Messinger, came along in The Whisper in the Gloom (1954). Clare is happy to accompany Strangeways on holidays, but in separate quarters, and she not only acts as an intelligent sounding-board the way Georgia did, but takes active part in his investigations, pointing out with her artist’s eye a similarity of bone structure in The Widow’s Cruise (1959); fighting off a pair of vicious attackers while Nigel lies unconscious in The Whisper in the Gloom; lassoing a killer in The Worm of Death (1961); and driving helter-skelter over country fields to stop a murder, “the car shaking like an ague patient,” in The Sad Variety (1964).

Mention should also be made of another important continuing character in the Strangeways books, that of Scotland Yard’s Inspector Blount. The two of them work together several times, and Blount, a hard-headed Scotsman, is no slouch—he pays great attention to detail and is no Lestrade-like foil. His ability to solve a crime nearly equals Strangeway’s. As the latter describes him in Minute for Murder:

“Nigel was familiar with the spectacle of Superintendent Blount putting a witness at ease. The courtly, considerate manner; the Pickwickian jollity; the appearance of slight obtuseness. He had seen clever people fall for it—seen them relax, and a consciousness of intellectual superiority creep into their faces or their words—ah yes, not so very formidable after all, I think I can twist him round my fingers all right. And Nigel had seen such people sadly discomfited.”

In this, we can see Day-Lewis’s talent for character description, and it can be found throughout the Strangeways novels in characters large and small, or simply in passing. A couple more examples:

Of Sir Archibald Blick in The Dreadful Hollow (1953):

“Thin, small, dapperly dressed, wearing an old Etonian tie and a thick black ribbon attached to his pince-nez, his face a map of wrinkles, he looked at first sight like a dandified, haggard baby.”

Of a row of author photos in a publishing house waiting room:

“The earlier ones ran to beards and expressions of quite unnerving self-confidence; as the eye moved on toward present times, the faces gradually lost both hair and assurance, the most recent being marked either by grinding Angst or by that pop-eyed, implausible bravado which looks out so often from the photograph files of Scotland Yard.”

In his lifetime, Day-Lewis was always wary that his work as Nicholas Blake might be taken by some critics as proof that he wasn’t sufficiently serious about being a poet, and indeed he did take some flak, one of them dragging him as “hiding his threepenny self in Nicholas Blake.” He also worried the other way—that genre fans would say him as too high-flown: “I have a feeling that people who read detective novels don’t like the detective novelist to be anything like a serious poet.” But the fact was, that his poet’s eye enriched his prose, infused his work with reflections of some of the greatest writers in literature—allusions abounded to Shakespeare, Camus, Dickinson, Dickens, Wordsworth, Yeats, Chaucer, Blake, Dryden, Marlowe, Coleridge— and added an extra something to the plots. He was quite simply one of the best.

He died of pancreatic cancer in 1972 at the home of Kingsley Amis and Elizabeth Jane Howard, where he and his wife were staying. As a great admirer of the novelist Thomas Hardy, he arranged beforehand to be buried near the author’s grave in Dorset. Among the children who survived him were Sean Day-Lewis, his biographer; Tamasin Day-Lewis, a well-known English television chef, food critic, and author; and Daniel Day-Lewis, winner of three Academy Awards for My Left Foot, There Will Be Blood, and Lincoln.

__________________________________

The Essential Blake

__________________________________

With any prolific author, readers are likely to have their own particular favorites, which may not be the same as someone else’s. Your list is likely to be just as good as mine—but here are the ones I recommend.

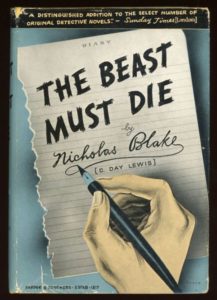

The Beast Must Die (1938)

“I am going to kill a man. I don’t know his name, I don’t know where he lives, I have no idea what he looks like. But I am going to find him and kill him….”

These are the opening words of Blake’s probably most famous book, and don’t they hook you immediately? The speaker is a man named Frank Cairnes, who writes detective novels as Felix Lane. “They are rather good ones, as it happens, and bring me in a surprising amount of cash: but I am unable to convince myself that detective fiction is a serious branch of literature, so ‘Felix Lane’ has always been absolutely anonymous. My publishers are pledged not to disclose the secret of his identity: after their initial horror at the idea of a writer not being connected with the tripe he turns out, they quite enjoyed making a mystery about it. ‘Good publicity, this mystery stuff,’ they thought, with the simple credulity of their kind, and started whacking it up into quite a stunt. Though who the hell of my ‘rapidly-growing public’ (the publishers’ phrase) cares two hoots who ‘Felix Lane’ is in reality I should very much like to know.”

Cairnes’ young son was killed by a hit-and-run driver, the culprit was never found, and Cairnes has made it his life’s mission to do so. Using his detective-writer’s skills, he slowly pieces it together, insinuates himself into the man’s household, and waits for his moment. All this comes in the form of a first-person diary, his “confessor,” but what follows then is nothing like he expected, and it takes the intervention of Nigel Strangeways, who enters halfway through the book, to figure out just what actually happened—and deliver his own brand of justice. A masterpiece of shifting perspectives and a deep dive into not one, but two, twisted psyches.

Minute for Murder (1947)

From the dedication: “I hereby assure my late colleagues, to whom the book is dedicated, that, whereas every disagreeable, incompetent, flagitious or homicidal type in it is a figment of my imagination, all the charming, efficient and noble characters are drawn straight from life.”

This is the novel set in the Ministry of Morale just months before it’s likely to be shut down—V-E Day has come and gone; V-J Day can’t be far behind. Nigel reflects to a colleague: “What I was thinking is—how little we know about each other. Of course, the place has always been full of gossip. But it never meant much; there was no malice in it, no deep curiosity really. We’ve been working too hard to have strong personal feelings. Or at any rate, we’ve repressed them, in the interests of making an efficient division and helping to win the war, and because blitzes breed a certain tolerance for one’s fellow blitzees. But now everything has slacked off, don’t you think all those repressed personal feelings are going to rise to the surface? In fact, haven’t they begun to, lately?”

Unfortunately, he is all too perceptive. Those repressed feelings erupt at a small office celebration for a war hero listed as “Missing. Believed killed” who is in fact alive and kicking, having nabbed a top-ranking Nazi (by posing as a woman!!) and returned home in glory. All sorts of invisible currents, both personal and professional, are zinging around the room, and they reach a climax when one of the attendees collapses before their unbelieving eyes from cyanide poisoning. What emerges next is a cavalcade of crime—blackmail, treason, arson, murder. Oh, it’s luscious. The plotting is ingenious, the characters wonderful, the psychology fascinating.

The Morning After Death (1966)

“‘Well, what do you make of us,’ he asked abruptly.

‘I’ve not been here a week yet. Too early for generalizations,’ Nigel said.

‘If you can’t make generalizations in the first few days, you’ll never make them.’

‘That’s probably true, but I’m not a journalist.’

‘Uh-huh. And I suppose every goddamn student in the place has asked you how Cabot compares with Oxford.’ Josiah puffed a cloud of smoke over Nigel’s head.

‘Quite a few. And they really seem to want to know.”

‘That is typical of the American student. He believes that indiscriminately sucking in information is equivalent to acquiring knowledge.’ The eyes rolled.”

This is the final Nigel Strangeways novel, set at “Cabot University” in Cambridge, Massachusetts, filled with delicious commentary on academia and America, not to mention a fine murder plot. As we all know, nothing is as vicious as an academic vendetta, and this one includes three brothers on the faculty—in the English and Classics departments, and the Business School—their overbearing, censorious father; an Irish poet in residence, “whose mental age—like that of most poets—seemed to oscillate wildly between nine and ninety;” a firebrand grad student from the “neighboring women’s college” who may “not be a very balanced girl;” her brother, who may or may not be a plagiarist; and poor Nigel Strangeways, who is at Cabot to do research, and desperately trying not to get sucked into the murder investigation, but failing miserably. It all comes to a head in a dramatic, frenzied, action finale at the big Yale-Harvard, uh, Cabot football game, with the culprit hurtling from the Cabot Bridge into the river far below.

__________________________________

BOOK BONUS

__________________________________

Sixteen of Blake’s twenty books were Nigel Strangeways novels, but four were standalones: A Tangled Web (1956), A Penknife in My Heart (1958), The Deadly Joker (1963) and The Private Wound (1968). Of these, I’ve only read Penknife, which, though its concept is highly derivative of Strangers On a Train, nevertheless puts its own spin on it. The Private Wound is said to be semi-autobiographical, featuring an Anglo-Irish novelist and clergyman’s son—like Day-Lewis—caught up in pre-WWII intrigue and violent passion in a remote part of Ireland. It’s reputedly pretty powerful.

__________________________________

MOVIE BONUS

__________________________________

The great French director Claude Chabrol, a master of the psychological thriller, did a version of The Beast Must Die in 1969, called Que La Bete Meure. I imagine it’s well worth seeing, though, interestingly, it leaves out the Strangeways character entirely. An Argentine version was also done in 1952, called La Bestia Debe Morir. And exciting news: In September 2018, the BBC announced that it was doing its own adaptation! It’s being set up as a series of five or six episodes and, if successful, could lead to more Blake adaptations.

The only other Blake made into a movie was The Whisper in the Gloom, a political assassination plot. Much of the book is seen through the eyes of several young boys, so I suppose it’s no surprise that the movie came out from Disney in 1980 as The Kids Who Knew Too Much.

One other fascinating could-have-been movie: When Orson Welles first made his three-picture deal with RKO, he was planning to start with Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. The budget ballooned, however, and WWII began, cutting into the European market, so it was abandoned, and Welles decided to make a quickie thriller— Blake’s The Smiler With a Knife. He wanted a bit of a comedic edge on it, so for the role of Georgia Cavendish, he sought Carole Lombard, then Rosalind Russell, then Lucille Ball. None of these possibilities worked out, however, and he had already spent a lot of RKO’s dough on Heart of Darkness, so he put that aside, too.

He had, though, planned to include a newly-invented part for himself in Smiler, that of a villainous Hearst-like newspaper baron. Maybe Smiler wouldn’t work, but…

The third time was the charm. The first film on Welles’ RKO contract was Citizen Kane.

__________________________________

META BONUS

__________________________________

From Minute for Murder (1947):

“An awful lot of people would be inoculated against crime forever if they could see one police investigation—the real thing—from beginning to end.”

“Crime Doesn’t Pay series, eh?”

“No. They’re too dramatic, too box-office. It’s the slow, tireless, meticulous, cumulative, boring side of an investigation; the spectacle of a stout, fatherly-looking gentleman in a bowler hat leaving not a single pebble on a whole beach unturned; that’s what would unnerve any misguided person who was contemplating a felony.”

From The Corpse in the Snowman (1941):

“The trouble about detective novelists is that they shirk the real problem….The problem of evil. That’s the only really interesting thing about crime. Your ordinary four-a-penny criminals, who steal because they find it the easiest way to make a living, who murder for gain or out of sheer exasperation—they’re of no interest. And the criminal in the average detective story is duller still, a mere kingpin to hold together an intricate, artificial plot, the major premises of an argument that leads nowhere. But what….what about the man who revels in evil? The man or woman whose very existence seems to depend upon the power to hurt or degrade others?”

From The Morning After Death (1966):

“Mrs. Edwards bent forward and eyed Nigel solemnly. ‘Considering what I’ve heard of your background,’ she said, ‘tell me, do you read detective fiction?’

‘Sometimes,’ said Nigel.

‘I hope you are sound on it.’

‘Sound?’ asked Nigel.

‘As an art form.’

“‘It’s not an art form. It’s an entertainment.’

May nodded approvingly. ‘Excellent. I have no use for those who seek to turn the crime novel into an exercise in morbid psychology. Its chief virtue lies in its consistent flouting of reality: but crime novelists today are trying to write variations on Crime and Punishment without possessing a grain of Dostoevsky’s talent. They’ve lost the courage of their own agreeable fantasies, and want to be accepted as serious writers.’ This seemed to annoy her.

’Still, novels that are all plot—just clever patterns concealing a vacuum—one does get bored with them. I can understand readers getting sick of blood that’s obviously only red ink.”