Nancie Clare

Les is definitely driving this bus.

Leslie Klinger

Nick and I have been friends for a long, long time. I met him back in The Seven-Per-Cent-Solution days, a really exciting times for Sherlockians because Nick, almost single-handedly, brought Holmes out of retirement. Public interest in Holmes came in waves, but [at the time The Seven-Percent Solution was published in 1974], they’d receded. The previous wave had been the Rathbone films in the 1940s and early 1950s. There was a long, quiet period during the sixties. And then in 1974, this new wave came crashing onto the shores, a book called The Seven-Per-Cent Solution by Nicholas Meyer, a guy that Sherlockians had certainly never heard of. And so take us back to those days, Nick. Where did this come from? Had you been a lifelong reader-writer?

Nicholas Meyer

Well, I was a lifelong writer. I started writing when I was five.

I grew up in Manhattan. I began by dictating stories to my dad who was a psychoanalyst, the definition of which is a Jewish doctor who can’t stand the sight of blood. He would write down the stories that I would dictate about how dog carried the newspaper home from the grocery store. Then he said, when I was maybe six, “You have to do your own writing from now on.” And that’s really when I started. When I was eleven, he gave me The Complete Sherlock Holmes to read. I inhaled it as people do.

Apropos of my writing ambitions, my father said, “Art students go to museums, and they’ll sit with easels in front of masterpieces and try copying them. So, you should find a literary antecedent, or something that you like.” Big surprise, I picked Sherlock and started writing these sort of high school versions of Doyle. And then I forgot about that for a long time. I was busy being miserable in adolescence. People used to tease me and say, “Oh, your old man’s a shrink. Is he a Freudian?” I didn’t know. So, I asked my dad, “Pop, are you a Freudian?” And he said, “Well, it’s really a kind of silly question.” I said, “Why?” And he gave me a backstory. “Look, when a patient comes to see me, I look at how they’re dressed, I’m curious about what they say. I’m very interested about what they don’t say. Are they on time? I’m curious about their body language. I am, in short, searching for clues from them as to why they’re not happy.” And I said, “Gee, Pop, that sounds like detective work.” And he thought about it. He said, “Well, yeah, I guess it is like detective work.”

And then a little light bulb went off in my head. I realized who my dad had always reminded me of because he would say things at the dinner table like: what do you think about a guy who always shows up five minutes late? And we’d all speculate about that.

I found myself wondering: how much did Arthur Conan Doyle know about the life and writing of Sigmund Freud? And the next thing you realize is: oh, they’re both doctors. Wait a minute! They’re both doctors who write! Oh yeah. And they died within nine years of each other. Oh! And [they died] in the same town. So, these coincidences were piling up and: oh, wait a minute, wait a minute! They’re both involved with cocaine. I’m thinking about all this in my pea brain.

Another ten years goes by, by which time I’ve moved to California, I’m seeking my fortune in the movie industry, and the Writer’s Guild goes on strike just when I’ve had a couple of TV movies made and was starting to sort of understand all this. I didn’t realize that we go on strike every chance we get, and you picket every day.

The woman with whom I was living said, “Now you can write that Holmes-meets-Freud story that you’re always talking about because you’re not allowed to write screenplays. And aside from walking up and down carrying a sign, I didn’t have anything to do. So that’s when I wrote it.

Leslie Klinger

Was the first novel that you tried your hand at?

Nicholas Meyer

Well, no. I wrote bad novels before, but I didn’t let ’em out of the house. I caught ’em a couple of times trying to sneak out, but I grabbed them just in time and shoved them into a drawer. My agents on the West Coast had an East coast branch—the literary branch—and I sent it to the East Coast. They said, “Well, I’ve never read any Arthur Conan Doyle, so how could I tell if this was any good?”

Now I’m very even-tempered and smooth and modest. Back then I wasn’t as modest. I had shorter fuse. And I said, “You call yourself a literary agent. And you’ve never read any Arthur Conan Doyle?” She hung up.

I didn’t quite know what to do. I took the manuscript and put it in a paper bag and flew to New York with the remainder of my life savings. I knew one person in the publishing business who was at Macmillan. It was pissing rain. And I walked in, dripping on the receptionist’s carpet, and said, “Is Jim so-and-so here?”

She said, “Oh, he doesn’t work here anymore.”

It had not occurred to me to maybe call ahead. Somebody said, where ignorance is bliss ’tis folly to be wise. If I’d called ahead, I wouldn’t have gotten on the plane. But I was in New York. I said, “Is he still an editor?” They said, “Oh yeah, he’s over at Hawthorne.”

I went in the rain with my soggy paper bag over to Hawthorne, and he came out and said “Hello. I thought you went west and blah, blah.” I said, “I’ve written a novel.”

He says “This is mainly a nonfiction house.” I was pretty tired by then. I said, “Look, I don’t know anybody else. I’m just leaving it with you and going home,” which I did. And then about five or six days later, he called me up and said this one they’ll publish.

And I’m damned if the agency, I can’t remember what their name was, is going to make 10% on my selling a book after they hung up on me. I knew this guy who I had met at somebody’s house, an entertainment lawyer. I called him up and told him what happened.

He reads the book, he calls me says, “Listen, we can’t go with Hawthorne. They’re a nonfiction house. Your book is going to get lost. Let me deal with this.”

I said, “Wait a minute, wait a minute. They offered X amount of money!”

He said, “Trust me, let me deal with this. They’ll understand.” So, I moved to Harcourt Brace, and then I got very bogged down in the copyright issue, which Les has so kindly solved for everybody. But this was before Les was born, you see?

Finally, I managed to make a deal with the Conan Doyle Estate, no, seven-per-cent solution, I can tell you. I got permission, but Harcourt Brace hadn’t lifted a finger. Then it went over to EP Dutton. I forgot your question…

Les Klinger

I can’t remember the question either…

And all of a sudden, the book is number one on The New York Times Best Seller List.

Nicholas Meyer

Actually it stayed for 40 weeks. No one was more surprised than Mrs. Meyer’s oldest, I can tell you. When I finished it, I thought, this has got to be publishable. That was my take on it. I don’t think artists are the best judges of their own stuff.

The Seven-Per-Cent Solution won the Gold Dagger from the British Crime Writers Association. That was the dagger in my cap.

Les Klinger

Then I assume Dutton said to you, “We want another book just like that one except different.”

Nicholas Meyer

Yes. I was very surprised by this, again, because of my more than gothic ignorance about how anything worked, including the two things about art I ought to have known: Art is all about cut and paste; and art is all about sequels. I think it’s fair to say that The Odyssey is a fanboy sequel to The Iliad. It’s all the same people, and they have more adventures. Dutton wanted another Holmes book. And I wasn’t really sure about getting into repeating myself and so on, but everybody I talked to said “do it.” I was at dinner with Francis Coppola, with whom I was destined to work somewhere down the line, and I said, “Why did you do Godfather Part II?”

This was three days before he got the Oscar for it. He said, “Well, first they backed up a truck with a lot of money in it. And I thought this would be money that would give me the opportunity to fail, which is to say the opportunity to try things. Fuck you money, rainy day money. Art is a very uncertain calling from an economic standpoint, sock this money away and you get to do something that maybe you would like to do.” And, by the way, Francis has absolutely been true to that his whole life. So that was a good rationalization or rationale for me to write The West End Horror. And that also was a bestseller.

Les Klinger

And then what? You were tired of it? The publisher said, forget it. We don’t want to do another one? There was a long gap before The Canary Trainer came out, in…

Nicholas Meyer

’95.

Les Klinger

Long gap.

Nicholas Meyer

Very

Nicholas Meyer

My ambition in going to Los Angeles was to make movies. And I was lucky, and luck plays a big part in all of this. Lucky with the people I’ve come to meet who’ve put up with me or helped me. I was very busy making movies. And I wrote The Canary Trainer because I had spent a year on a deal, actually a deal involving Francis Coppola, that wasn’t coming together. Eventually it did, but I needed to make some money…

Les Klinger

Sort of like Conan Doyle, who turned back to Holmes when he needed to make some money.

Nicholas Meyer

Well, Dr. Johnson said, “A man is a blockhead who writes for any other reason.”

I was in a bookstore in London where I lived for five years, and I saw a copy of The Phantom of the Opera. I didn’t even know it was a book. And in the introduction, it said, “God, it’s interesting that Holmes never matched wits with the Phantom because the dates all work out.” I just stood there and the hairs on the back of my neck going statically aloft. And then I looked around to see if anybody saw me holding this book. I bought this book and went home, and it was just an idea that wouldn’t let go. And the short answer about all seven of these books, because number seven is in the pipeline, is that I only write them when I get ideas that seem to be good for Holmes to deal with. Otherwise, I can go 20 years without doing it.

Les Klinger

I remember one conversation in which you wanted me to help you fill in some blanks…

Nicholas Meyer

I’m always asking you for that…

Les Klinger

Patches in Holmes’ career, as we know it, when we don’t know what was going on…

Nicholas Meyer

I play by the rules!

Les Klinger

I know you do. So as perhaps a boring aside to everybody except the Sherlockians. You were a Sherlock Holmes fan back when you and I met in 1976 or something like that. I think you had actually been to some of the local club meetings…

Nicholas Meyer

When I got to LA, there were lots of bookstores back then. And in one of those bookstores, I stumbled on a book of essays by Trevor Hall about Sherlock Holmes. I never knew there were writings about the writings. I started spending all the money I didn’t have, finding these things in secondhand bookstores and reading all this ancillary commentary or pastiche essays: Holmes and music, Holmes and women. I was having the time of my life. Of course, I wasn’t doing any work. And people said, what are you wasting your time with? And I said, “But it’s so fun!” All of that went into Seven-Per-Cent when I finally got around to writing it.

Les Klinger

The story I’m about to tell may be apocryphal, but you were invited, as I recall, to a meeting of the Baker Street Irregulars in New York. And at that time…

Nicholas Meyer

After The Seven-Per-Cent Solution was a hit…

Les Klinger

And you said something like, “Good, my wife and I will be pleased to attend…”

Nicholas Meyer

I didn’t have a wife. I had a girlfriend, and I thought, great, we’re going to go to New York. We’ll stay at the Carlysle. We’ll have this really hot weekend or whatever it is. And then the director of the Holmes Society, the Baker Street Irregulars said, “I assume you know that women do not attend the meetings.” And I was really dashed. And I said, “Oh, no, I didn’t know that. Do Jews?”

Les Klinger

Many Jews

Nicholas Meyer

He wrote on postcards. He said, “It’s a tradition.” And I wrote back, “So is lynching.” I declined to attend. But eventually…

Les Klinger

I think it was the nineties when you were the distinguished speaker, in fact, the first distinguished speaker for what’s now a twenty-five-plus year series of lectures. You gave a lecture on writing pastiche, the motivation and the Irregulars? I think at that point, maybe you’d mellowed…

Nicholas Meyer

Definitely have mellowed. I’ve been mellowing for years. I’m about to go from mellowing to rot.

Les Klinger

And by then women were in fact allowed to participate in the Irregulars. To my everlasting shame, there was that era where women were excluded. But in any event, you’ve been a member of the Baker Street Irregulars now for many years.

Nicholas Meyer

Yes. I’m a member in good standing.

Les Klinger

Somewhere along the way you said to yourself: Mexico, I should take a trip to Mexico because I need a deductible vacation. So, you took yourself to Mexico to do research. Was the idea pretty fully jelled at that point for the new book, or…

Nicholas Meyer

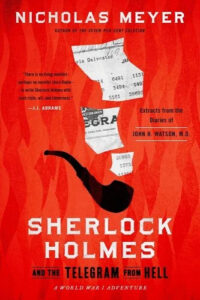

Not only was it jelled, but it had been written right up to the point where I needed to go to Mexico. There are [long] intervals between The West End Horror, The Canary Trainer, The Adventure of the Peculiar Protocols and The Return of the Pharaoh because it takes me a long time to think, “This would be a good idea for Holmes.” I am neither a fast nor a prolific writer, particularly of books. And for years, I had had this idea about a Holmes novel that revolves around a certain real telegram.

People sometimes ask: how long does it take you to write a book? And I’m sure Les can speak to this as well, there’s a distinction between the physical act of writing and the working out how you’re going to do it. The Protocols, was ten years thinking about that idea before I stumbled on a way that seemed to be good.

I was working on Sherlock Holmes on the Telegram from Hell for about a year before I actually started writing something. And meanwhile just writing all kinds of miscellaneous notes that float around here like nobody’s business.

I finally got to the part where Holmes and Watson need to go to Mexico City, and I hadn’t been there since 1985, when I made a cute little comedy with Tom Hanks and John Candy there called Volunteers. This trip was a bit like a location scout, the most fun part of making the movie because there’s no movie. You’re just eating a lot of good food in exotic places and looking at whatever interests you. I went to the Western Union office in Mexico City where this telegram was sent, and it’s a museum. It looks like Versailles because it was built by Porfirio Diaz who was Mexico’s president for thirty-five years. Paris was big influence. And there was a whole exhibit about this telegram. That and a lot of other stuff that I learned while I was in Mexico, which enabled me to finish the book.

Les Klinger

There are some real historical figures in the book as well.

Nicholas Meyer

The book is largely true. I just managed to insert two fictitious characters without disarranging what really happened. I think the ships are real, that even the submarine is real. That’s why it took so long.

Les Klinger

This is the pattern that you adopted pretty early on. Seven-Per-Cent Solution is pretty much free floating; it’s a patch of time we know very little about. But West End Horror is not…

Nicholas Meyer

Everybody— Ellen Terry, Henry Irving, George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, Bram Stoker, Gilbert and Sullivan, Richard D’Oyly Carte—in The West End Horror was doing what they were actually doing in the first week of March 1895.

What was historical about The Seven-Per-Cent Solution was that Freud had gone off cocaine by that time. He didn’t publicly recant, but it was not farfetched to assume that he was helping people get off the drug because a friend of his had died of it. I was still coloring within the lines. Maybe there were more fictitious characters in it.

Les Klinger

Well, you were certainly coloring well within the canonical lines of the published Sherlock Holmes stories, but it was less, “I’m going to insert Holmes and Watson into historical…

Nicholas Meyer

…Elements. That was what happened with The West End Horror. It was a discovery I made along the way rather than a plan. Once you decide to use a real event, you find yourself connecting to the real people who were connected to the event. I don’t think it was a deliberate pattern on my part. If you can find anything deliberate in my life, I’ll give you a nickel.

Nancie Clare

You hinted that there might be another…

Nicholas Meyer

Yeah, I’m on the home stretch, as it were.

In the next couple of months, I hope it’ll be finished. When Mysterious Press bought Sherlock Holmes and the Telegram from Hell, it was a two-book deal. I said, “Really? It has to be a Holmes book?” [They said,] “Yes.” I had no idea, but I said “Yes,” because the money, the money, the money! Anyway, the money, and I had no idea what I was going to write about. I don’t usually get ideas; people give me ideas. Somebody gave me Sherlock Holmes and Freud and the cocaine connection. My agent said, what about Holmes in Egypt? And I thought, that’s really good. And that was The Return of the Pharaoh. The Protocols was me thinking up something, The Canary Trainer, I stumbled on, but it’s very hard for me.

And then suddenly, in no time, like crossing the street after I’d said yes to this second Holmes book, which would be the seventh, I suddenly knew what I wanted to write about. It’s called Sherlock Holmes and the Real Thing. And it’s about art forgery. And that came about because in 1974, when I was sent on a book tour by my publisher, back when they sent you on book tours, I landed in Pittsburgh in a very big thunderstorm and a reporter who had been dispatched to talk to me since it’s was a different world back then, was a guy [thinking] “why am I talking to this whipper snapper about his Sherlock Holmes book?” He said to me, by way of greeting, as I was shakily getting off the plane. “So how does [it feel to be] a successful forger?”

And that stopped me in my tracks. And I said, well, [the book] doesn’t actually say “By Nicholas Meyer.” It says, “As edited by Nicholas Meyer.” And I don’t remember what happened after that, but he got his hooks in me. I realized I am a forger, and that got me interested in forgery. I’ve spent the last thirty, forty years reading up and collecting books about different kinds of forgery. And suddenly I thought, this is the perfect thing to put all that reading to some use. I think the way I get interested in things, going back to that Trevor Hall book of Holmes essays, is just start doing these things for fun, but in the end, they’re all grist for the mill. Everything, everybody you meet, everything. Writers are not to be trusted.

Les Klinger

What is what they say? Write what you overhear?

Nicholas Meyer

I like that one.

Les Klinger

So, this is Holmes and Art Forgery. Interesting. There are some famous forgers in history, what’s the year?

Nicholas Meyer

Well, I wasn’t going to lay this on you in public, but basically I’m going to leave it to you to determine the authenticity of this manuscript, but no pressure. I will turn it over to you as a found manuscript and say, “Do you think this is real?” And you can make up your mind. You will have to determine from internal evidence whether this tracks or could be made to track.

Les Klinger

Okay, I look forward to it.

Let’s see, I know I have a book somewhere. David Randall’s The Adventure of the Notorious Forger…

Nicholas Meyer

Is it a Holmes book or…

Les Klinger

Yes.

Nicholas Meyer

Oh my God, you just spiked my guns! Why am I finishing this thing?

[NB: David Randall, an antiquarian bookseller, early member of the Baker Street Irregulars and creator of the famous Scribner’s catalog of Vincent Starrett’s collection of Sherlockiana in the early 1940’s, stuck to what he knew when he wrote The Adventure of the Notorious Forger in 1978. The story pits Holmes against Thomas J. Wise, the real-life “notorious forger,” who was responsible for forged first editions of such authors as Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Alfred Tennyson.]

Les Klinger

I don’t know there are, what, 5,000, 10,000 Sherlock Holmes [stories] that have been published. If you said, “I’m doing Sherlock Holmes meets Mickey Mouse,” it wouldn’t be unique.

It’s not about the ideas. Ideas are a dime a dozen, as you know. It’s all in the execution. So, it doesn’t matter how many other people have written about art forgery. Nick, you are a fine writer. And it’ll be worth reading.

Nicholas Meyer

It’s worth reading up until page 200. I can tell you that.

Les Klinger

You can use that as a blurb, even though I haven’t even read the book.