Nick Cutter is the author of the critically acclaimed national bestseller The Troop (which is currently being developed for film with producer James Wan), as well as The Deep and Little Heaven. Nick Cutter is the pseudonym for Craig Davidson, whose much-lauded literary fiction includes Rust and Bone, The Saturday Night Ghost Club, and, most recently, the short story collection Cascade. His story “Medium Tough” was selected by author Jennifer Egan for The Best American Short Stories 2014. He lives in Toronto, Canada.

Andrew F. Sullivan is the author of the novel The Marigold. His short story collection All We Want is Everything and his debut novel Waste were both named Best Books of the Year by The Globe and Mail (Toronto). He lives in Hamilton, Ontario.

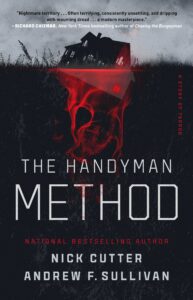

Nick Cutter and Andrew F. Sullivan are most recently the co-authors of a new horror novel about an evil YouTube handyman, called, appropriately, The Handyman Method. They were kind enough to set down some questions and answers for CrimeReads about the cowriting process, their Canadian horror forebears, and how scary stories are sometimes the best way to capture ordinary experiences.

Andrew F. Sullivan: Why did we decide to co-write a book together? Who would curse us with this?

Nick Cutter: I’m sure we did some awful thing in a past life. Probably started the Black Plague. No, I think it’s a great opportunity, one that rarely presents itself. Yes, sure, writers are often buddies. Or antagonists! But even those who are friends, well, we’re often siloed by our aesthetics, our preoccupations, or simply by our natures and the nature of writing. We’re lone wolves! So it’s not often that two have the opportunity or the desire to come out of our separate caves and go on the hunt together. A hunt … for story!

Anyhoo, it’s about finding that right vibe, that yin and yang, a way to harmonize two people’s ideas and fixations and tonal differences in a single and hopefully cohesive project, between two covers. I believe you and I have done that, and remained buddies, though there was some rough sledding there—not on the personal front, but just us trying to push the narrative through its paces. That happens with most books, but in those instances you’re left to suffer through it alone. Nice to not have that this time, and have someone to lean on.

So, as to the “How Did You Maniacs Come up with this Idea?” question—the Big Meaty Ideas sprung from your noggin, as I recall. So what was driving them, for you?

AFS: The great question that haunts us all. The origins of The Handyman Method for me came from the parasocial relationships I saw growing between folks and online personalities, the atomized nature of modern relationships. People build one-way friendships and relationships with personas and the internet has only made that more prominent. So maybe there was a little bit of Scorsese’s The Kings of Comedy in there, and some Adult Swim content too, the surreal edge of a “Too Many Cooks” or “Unedited Footage of a Bear” at two in the morning. I feel a great unease whenever I see someone talking into a camera, sharing an intimacy that isn’t there, a relationship that by its very design is going to be one-sided. And so let’s drop a hint of malice in there and stir it up.

The home improvement aspect probably sprang from my own life. Yes, I have used the internet to fix a toilet. And I did a great job. But there are certain tasks you can’t handle on your own. You are only a few clicks away from seeing yet another renovation disaster. The online horror of “Groverhaus” looms over anyone attempting home repair. Bumping up against your inadequacies and insecurities was always a big part of this story for me. Sometimes there are things you can’t solve. So what if you make a little bit of a Faustian bargain with a man on the other side of the screen? What if he says he can fix everything? Handyman Hank was summoned to solve that problem. He has the answers. And the tools.

With that, I think we were off to the races. And the horrors.

Speaking of horrors, your work is often cited as extreme by some horror readers with a real commitment to showing the horrible consequences and outcomes for your characters that other writers might shy away from. To me, it’s always felt very grounded in the characters and the world you’re presenting. How do you see your work in the lineage of body horror, following the likes of Clive Barker or our own Canadian father, David Cronenberg?

NC: What Clive did, and what I couldn’t quite grip when I first read him—too hormonally undeveloped, was I—is find that sweet/sour spot between horror and sexuality/sensuality. The idea, one of the core themes of The Hellbound Heart and other Barker works, that the human nervous system can experience so much pleasure, an overabundance of pleasure, that it becomes a form of torture … that’s in so much of his work, and it clearly made an impression even if I didn’t know what to make of it as a young’un; all I knew is that it made me feel interesting feelings. That punk-rock S/M of the Cenobites, right? That whole pantheon of demonic … what did he call them? Architects. But also the idea of the body as this structure that could be corrupted, that was intensely breachable, and could be horribly changed or altered … sometimes to the joy of its owner?

John Carpenter and Cronenberg on the film side were influences. While Carpenter uses (to my viewing) body horror as a device for building tension and to offer sublime shock from time to time, I feel Cronenberg is dialled in on Barker’s frequency with Dead Ringers and Rabid and other films … and I think both David and Clive may’ve been subtly influenced by J.G. Ballard. Of course, Cronenberg made Crash based on a Ballard book, and I’d be surprised to find out Barker didn’t consume Ballard during his developmental phase … but then Ballard would’ve had his own influences, and that influencer his or her own influences, on back to the first Piltdown man or woman who slapped paint on a cave wall.

So, this book is coming on the heels of—but was actually written somewhat in concert with, editing one while writing the other—your new book, The Marigold. What are some of the bugaboos you investigate in that book, and that you may’ve found yourself obsessing over even while neck-deep in Handyman?

AFS: You know I didn’t really think about the parallels until after The Marigold was already out there as an ARC and we were pretty much just doing the proof edits on The Handyman Method. I find that often happens to me with my work, you don’t realise the themes or motifs underlying your work until it’s done. So obviously, a few things came to mind. Both books do end up being about buildings, places where people live, as sites of corruption. I do like to think of it as an extended bit of body horror, like you mentioned before. A place that is supposed to be safe and sacred becoming corrupted, actively killing you, whether it’s slowly or all at once.

In the case of The Marigold, it is a sentient mold made from the dead called the Wet that is looking for new bodies to join it. It’s an active, living thing performing this infiltration or corruption. It cajoles and beckons, but it also takes when it needs to. The willing meat is sweeter, but in the end, it will take it by force if it has to-–the Wet needs to feed one way or another. For The Handyman Method, I think the threat is a lot more internal, we have Trent wrestling with himself and visions of himself. There are greater forces at work, which we won’t reveal here, but it is a man actively making these choices that drive him to despair. So an obsession with home, an obsession with place, a belief that there may be a cosmic horror beneath our feet rather than just in the sky above us… part of it for me, is acknowledging how little we know or how little we comprehend. Horror lies in that absence.

One of the gaps for us putting together The Handyman Method was our ages and family situations. You’ve got about a decade on me and two kids and with this novel we are telling the story of a family. So how has that changed your approach to horror and this novel? The older work must feel different, how has your focus evolved with those major life changes?

NC: Yes, I will be ever grateful to you for administering my Geritol and tucking me in for a nap whenever I got cranky. But you’re right in that, as the novel evolved from its novella and short story iterations, it became more domestic. The idea of giving our once-single guy a family was, to me, natural. To give that man a son, 11 or so, and a daughter on the way eventually was in fact a literal fit with my own family at the time we were writing.

I think it also gave me an opportunity, on my side of the writing ledger, to approach some of my own inadequacies and the regrets I feel as a husband and father. While neither I or you are Trent, our character in the book, I can say that I, at least, do have thoughts come over me from time to time like a foul rash, having to do with—as best as I can psychoanalyse myself—the sense that my life is different and somehow lesser than that of my father and grandfather and all the way back. Which is dumb. Surely my Dad had such thoughts, and Grandpa … and Mom and Grandma, in their own ways.

And hey, maybe those thoughts ought to be investigated! Even the grottiest and most shaming ones, the ones your conscious and compassionate mind rejects the moment they bubble up from the primordial cesspool of your id … but bubble up they do, at least in my corroded ole noggin they do, and some part of my writing of Handyman was given over to looking those thoughts square in the face.

So, to square final accounts … the modern house as a temporary place rather than something that will last, what say you to this idea? Have we humans become the equivalent of hermit crabs?

AFS: That was part of what I kept circling back to with this book, this house in the middle of nowhere, the promise of a suburb to come. The idea that this kind of development is natural, when it’s not. It’s an illusion. I look at somewhere like Arizona and see places waiting for drought to wipe out entire neighbourhoods… but also that the homes we might build now are often flimsy, flammable, death traps within a few years of inhabitation. There’s a seed of that in this novel, I mean we open with a brand new home already splitting at the seams. Trent’s rage is real and justified in that moment. He knows he has been ripped off.

The house in this book is fragile. It’s not going to last. It’s a new build, it’s a nightmare, but it’s still plausible. There’s a mythology of “home” that it might be some eternal state, a place you can retreat to when things are bad, but that’s never really been true. Watching that get reflected in the material reality of the place matters and I think it’s something that has resonated with me. My favourite apartment was probably 100 years old. The walls were thick. The floors were solid. I knew if it stood that long it would probably keep standing. I think the terror of the modern house is that it can fall apart so easily. Instead of a few centuries, just give it a few decades for the natural world to say you were never really here.

And I think that connects with the family stuff too, there’s claims of great long lineages of “how things were done” or ways of being, but they’re usually false. The past is more complicated, complex, and contradictory than we want to admit. It doesn’t offer up easy answers. There was not always a better way of doing things, just someone telling you it was so. What is left is what wasn’t pillaged into ruins. We are scavengers. It’s what we do best.

Temporary is a state of mind, I suppose. There are tortoises in this world who will outlive me. There are forests that will see us as a blip. So, a house is just another shell we hope will outlast us, but we can’t even pull that off anymore. Unless there’s a video guide!

NC: Thanks, Andrew, this was fun. See you at Home Depot, Chief.

***