In all of spy fiction, there’s no one more ostensibly average than George Smiley, he of the “soft face” and “pudgy” hands, the narrow shoulders and woeful posture, the perennial gloom and wonderfully ironic surname. John le Carré’s fictional British intelligence agent features in about a third of his 26 novels, among them The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. Paradoxically, Smiley’s popularity seems to have precluded even more appearances. “There were always supposed to be more Smiley books,” writes Nick Harkaway, the author’s son and himself an established novelist. But in 1979, Alec Guinness played Smiley in a BBC adaptation of Tinker, Tailor—a job the actor did so well that this new “external Smiley” displaced “the one in (le Carre’s) head,” Harkaway says.

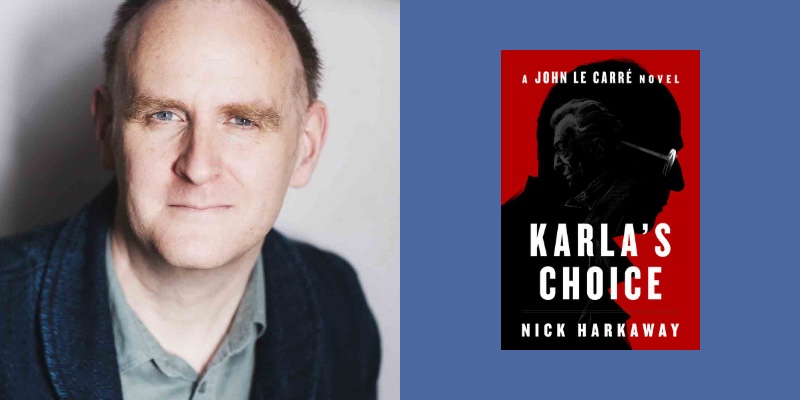

When le Carré, born David Cornwell, died in 2020, his will instructed his family to keep his work in the public eye. Which brings us to Harkaway’s new book, Karla’s Choice, in which the son takes up his father’s work. The book, dubbed A John le Carré Novel, is set in 1963, the height of the Cold War game of wits pitting the Circus—le Carré’s fictionalized MI6, the British intelligence agency that once employed him—against the Soviet spy apparatus. In nimble, occasionally wry prose, Harkaway spins a satisfying mystery about a Hungarian hitman’s plans to murder an émigré book editor living in London. The cast includes numerous characters seen in previous lé Carre novels, among them Smiley—“round-faced, round-bodied,” Harkaway writes, with “a watchfulness that touched everything, as if a fog were paying attention to the house it surrounded”—and his habitual foe, the increasingly powerful Soviet spymaster known as Karla. As is often the case in the le Carré canon, the action plays out against a backdrop of long-brewing transnational enmity, nurtured in places where, as Harkaway puts its, “there is only now, and it goes back forever.”

Speaking from his home in London, the author talked about growing up with Smiley, inhabiting his father’s narrative voice and whether we’ll see more of the Circus in future books.

You were born in the early 1970s and were in grade school when the BBC adapted Tinker, Tailor. So is it right to say that Smiley has always been a presence in your life?

Very much so. I was born in ‘72. My dad was writing the Smiley books all the way through the ‘70s, and I literally learned to talk hearing him read Smiley to my mother—obviously along with many other conversations. Part of my fundamental understanding of how language fits together, and particularly written language, comes from listening to Smiley being read in draft.

That’s remarkable.

That’s not something that occurred to me until about three days ago, but you asked me that question and I find myself thinking, Yes, it’s actually deeper than I had imagined when I started this project.

The decision to write the book was a kind of family decision?

Yeah. I’ve spent since 2008, when I did my first book (The Gone-Away World), trying to put clear water between myself and my dad’s writing, for every obvious imaginable reason. I’ve done pretty well, doing that. Back in the old days, when Twitter still existed in a form that I recognized, people would occasionally be caught up in my timeline, staggered by the idea that we were related. That’s great, you know? But then when my father died, obviously I was brought into this conversation around Silverview, the finished but unpublished le Carré novel.

You did some work on Silverview before it was published in 2021. How close to finished was that when you took it on?

It was a finished manuscript. When you give your publisher a book, they can come back with dozens of questions. Sometimes those questions are minor—-plurals of words, date formats, things like that. But some of them are a little bit heftier: Does this paragraph make sense? I think there are three or four places in Silverview where I actually did some writing, and there is one place where there is a paragraph that’s me. So it was tiny bits of nip and tuck. My job was to let it be itself as much as possible.

But even in that limited capacity, did it make the idea that you’d write a le Carré novel less daunting?

Not at the time. I thought, I got off easy here. I’d made this rash promise in something like 2013, 2014, where he said, Will you finish a book if I leave it undone? I said yes, and with Silverview, I didn’t have to take a two-third finished manuscript and produce a crash-bang ending.

But one of the things that we’re asked to do in his will is to try to broaden the reach of his work and to ensure its legacy, so that people continue to read it. The way in which publishers get people to pay attention is with new stuff. So as we were looking at what new stuff we could do, my brother ambushed me and said, You could write a book. In fact, I think you should. I decided to take a couple of weeks to see whether I can do this. If the answer is yes, then I’ll do it.

Did your father think there might be more new le Carré novels after his death?

I don’t think so. It’s really hard to know what he did and did not contemplate. He very conspicuously left us stuff. There are these extraordinary white boards of stuff, there is the archive, there are the notebooks and so on. He was a big destroyer of documents if he felt like it, so that wasn’t a casual decision on his part. Did he know that I specifically would produce a new book? No, he had no idea. And I had no idea. But when I ask myself the $1,000,000 question—What would my father say?— I realized that he told me the answer in one sense when he said, Will you finish my book if I die with it half done?

If I had gone to him and said, I’m gonna write a book into your universe, his question would have been, in the first instance, creative. It would have been, Do you know why you’re writing this? He would have been protective of me, not of the fictional corpus. The first answer that comes to my mind is I finally get the writing apprenticeship that I didn’t have with him. We didn’t really talk about writing. He showed me writing constantly, I saw him write, I learned by osmosis. But there was never a moment when he sat me down and gave me intensive instruction in writing. It’s an amazing thing for me as an emotional and a creative experience.

The le Carré novels have fun with the comic self-seriousness of Soviet bureaucratic language. You do too. In one scene, a man bursts into a room and says, “I am here to kill your (boss) on the personal instruction of a senior officer of the Thirteenth Directorate of the Committee for State Security of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.” It’s really funny.

He was always funny, but I had to tamp it down a bit because my books tend to be a little bit crazier, a little bit more comical. That was one of the few places where I had to turn the dial slightly. In the le Carré stories, there’s also a puncturing of British bureaucratic pomposity. I think he was conscious of the ways in which officials use language to bolster ridiculous positions and to draw on the authority of the state. If you puncture the pomposity, you take away the legitimacy of really horrible decisions.

How many times have you read the Smiley novels|?

Countless times, and specifically so often when I was younger. They were my touchstone. I would listen to the audiobooks on cassette to go to sleep, and that carried through until I was at university. If it was very late, I’d hear the Shipping Forecast from the BBC, and if I was still awake, I’d go back to Michael Jayston reading Tinker, Tailor.

How will you decide if you’ll write more Smiley books?

That’ll be straightforward. If people like it, I could do another of these—I could do several. It’s a joyful experience, but it can also become quite melancholic because Smiley is melancholic, and I find myself thinking of my parents. There’s a lot of catharsis in it, which is new to me and weird. I don’t generally write for catharsis. I write for joy and for fun, because I love it. So putting pain onto the page is a new thing. But the simple answer is, if people enjoy it, there is a reason to do more. And if they don’t, there are other things I can be writing.