Freud is not exactly renowned for his sense of humour, but he had a lot to say about jokes. While most of his work was on the subconscious urges behind humour, he also had more substantive theories about the actual mechanisms of a joke. For a joke to ‘work’, claimed Freud, three parties need to be involved: the victim, the aggressor, and a third person who gains gratification from witnessing the victim’s subjugation.

It is obviously a strain to try and apply this analysis to everything that is funny. My nephew’s favourite joke, aged four – “What goes up and down and wobbles? A jelly-copter” – doesn’t seem to offer much aggression in any direction (though admittedly I’ve never told it to a helicopter pilot or, for that matter, a pâtissier). But it’s a useful model for understanding the dramatic and emotional dynamics of books and their characters.

Most novels, of course, have more than two or three characters. The novel, historically, is an art form that recommends itself for its capacity. In the novel’s Victorian heyday, particularly, it was a form that could support huge casts, whose stories spanned lifetimes, generations, countries, continents. But there is also a kind of modern novel that is interested in drama on a much smaller scale – the microcosm of a pair of characters. Rather than offering a panorama, this kind of book boils a story down to a single relationship and examines it in all its intensity and claustrophobia. Often a restricted physical setting is used to impose even more emotional pressure – two ants under a magnifying glass.

So back to Freud: as soon as a third party is introduced to an inseparable pair of characters, dysfunctional or not, the relationship has the potential to unravel or more likely explode. It is a setup that feels perhaps more at home on the stage but is no less thrilling in the pages of a novel. When two become three, a game of tennis is no longer fair. In a trio, alliances can be formed. There can be a majority and minority. There are the right conditions for a joke. And – jelly-copters aside – a joke will always involve a victim.

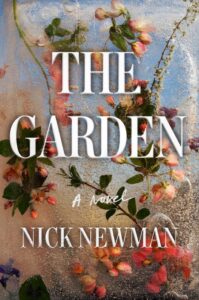

The Garden makes deliberate use of this dynamic, but it is indebted to many other authors who have made masterpieces of tension through a triangulating a single relationship.

We Have Always Lived in The Castle, Shirley Jackson

This book is unlike anything else I have ever read. It is perfect in its strangeness. Merricat and her sister Constance live a reclusive life of co-dependency after the deaths – or murders? – of their family. Their world is restricted to the family’s dilapidated house and gardens, with only occasional forays into the town, where they are considered pariahs. Their lives are regressive, recursive – Merricat in particular is trapped in a state of childlike dreaminess – and rotate only around each other. There is a third character present from the outset, sick uncle Julian, but he is more of a task to be dealt with, and he is completely outshone by the binary star of the two sisters. The split comes when they are visited by “cousin” Charles, who has designs on something kept in the family safe, and Merricat and Constance’s calcified, carefully regimented existence is disrupted beyond repair. Charles is the perfect example of the imbalance of a third party. Merricat hates him. Constance is seduced by him. Alliances are made and broken. By the end of the book the strain upon the sisters’ relationship proves unbearable, and their peculiar little world goes – quite literally – up in flames.

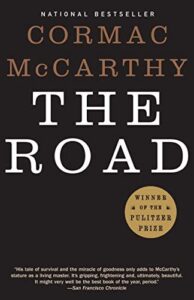

The Road, Cormac McCarthy

I don’t need to extol the virtues of a book that won its author the Pulitzer Prize. It is terrifying, it is heartbreaking – not for the bleakness of its world, but for the tenderness of its central relationship between the unnamed man and his son. Here is all of humanity, in its defiance, its frailty, its compassion. Here is vast, devastated open world, and yet it is a story of extraordinary intimacy – the boy and his father are a candleflame in the darkness, and we are not privy to anything that is not illuminated by them. The unbearable tension of the novel comes not from any intrusion into the pair, but from the threat of one. We read it in a state of total vigilance – knowing, really, that at some point two will become three, or perhaps one, and either will be catastrophic.

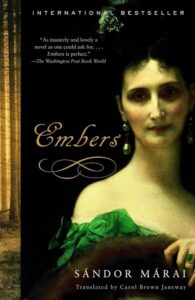

Embers, Sandor Marai

It’s a shame more people don’t know about this Hungarian novel – it is so exquisitely melancholy and offers a masterclass in the building of tension. In a gloomy castle at the foot of the Carpathian Mountains, an elderly man awaits the arrival of a friend whom he has not seen for over 40 years. He invites him in. They have dinner. They talk. And that is the plot in its entirety. But over the course of that one night, their lives are excavated, the visitor’s character forensically examined, and they dig and dig until they reach the bedrock of their relationship: the thing or the person that caused their estrangement in the first place. The third character in this novel never actually appears, but drifts like a ghost through the recollections of these two old men – only when she is fully fleshed does the novel reach its shattering conclusion.

Piranesi, Susanna Clarke

Maybe my favourite book of the last ten years. There are few novels – or films, or video games, or anything – that offer up a world so original and strange and so fully-imagined. To read it is to step into another person’s dream. It is, for the most part, another two-hander, told with charming naivety and curiosity by the title character, who inhabits the infinitely roomed House along with an unnamed “Other”. It is perhaps slightly different from the other books mentioned here, in that Piranesi hardly has a relationship with the Other – in fact, his first love is the House itself. From their occasional interactions, though, he is happy to believe that the two of them have a friendship of sorts. But the rule of three is merciless. When the Other warns him of a third intruder in the house who means him harm, the relationship sours, the world unravels, and the guileless Piranesi finds himself a pawn in a much larger and more sinister game.

Of Mice and Men, John Steinbeck

Almost a century ago, John Steinbeck got there before anybody with this lean, devastating tale of a doomed pairing. There is a savage tenderness to the relationship between George and Lenny – a strange, hard-boiled kind of love that you think might have survived if only they had never met another human being. The opening is almost reminiscent of The Road, George appearing as Lenny’s ornery father figure, making sure he doesn’t drink too much, that he doesn’t make himself sick; the landscape of the dustbowl is almost as bleak as McCarthy’s ashen wasteland. It’s only when the two of them arrive at Curley’s farm and others try to recruit, to dupe, to exploit them – and vice versa – that the quivering equilibrium of their friendship is disrupted. As with almost every book here, the tragedy and the tension of the novella is that the reader can see, within the friends’ first exchange, that they simply aren’t made to withstand the unforgiving world of men.

***