There’s nothing quite as delicious—or terrifying—as a locked-room whodunit. A handful of suspects, sealed off from the world. A victim no one can save. And a killer who must be among them. It’s a puzzle for readers and writers. But it’s also something deeper.

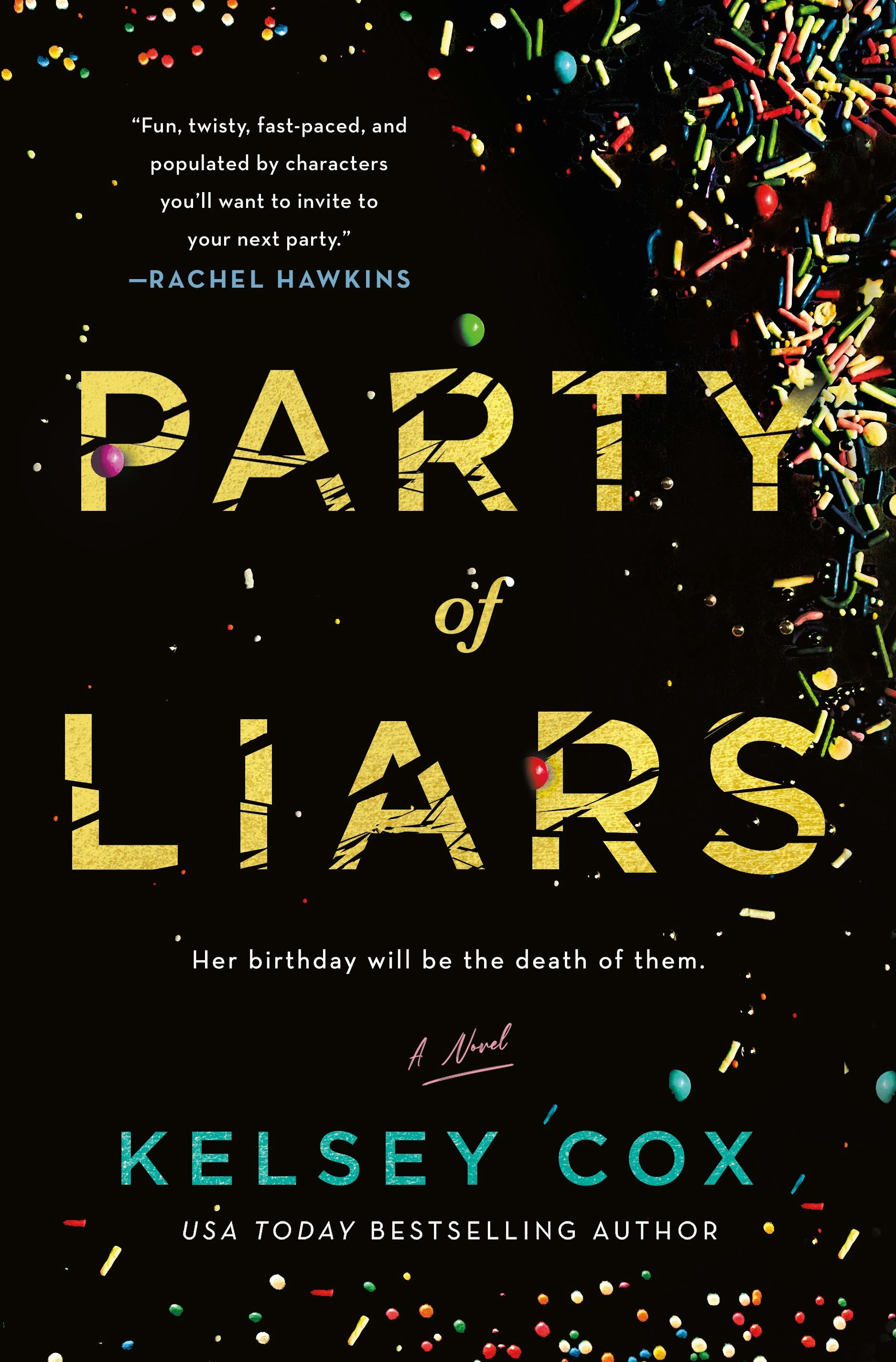

Because the real walls aren’t always brick and mortar. Sometimes they’re the secrets, obsessions, and lies we trap ourselves in. As I wrote Party of Liars, I realized the locked-room trope wasn’t just a plot device—it was a mirror of how we live inside our own psychological prisons.

Locked-room mysteries have fascinated readers for centuries, from Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None to modern twists like Ruth Ware’s The Woman in Cabin 10 and Lucy Foley’s The Hunting Party. On the surface, they’re about solving an intricate puzzle: who had motive and opportunity? Who do I most suspect? Who could be a wolf in sheep’s clothing? Whose lies do I believe? But beneath the puzzle lies something more primal: claustrophobia.

When you trap characters in a space together—whether it’s a country house, a luxury yacht, or a single bedroom—every secret, flaw, and grudge becomes impossible to ignore. People are forced to face not only each other, but themselves. In the confines of a locked room, politeness peels away. The civilized mask slips. And underneath, fear, guilt, and rage start to bubble.

Because locked rooms aren’t always made of walls and doors. Sometimes, the true prison is emotional: The marriage you feel stuck in. The lie you told years ago that still controls you. The guilt you carry for something you did, or didn’t, do.

In Party of Liars, I wanted to explore how physical confinement mirrors psychological entrapment. My characters are trapped at a Sweet 16 party, but they’re also trapped in webs of secrets, betrayals, and dangerous desires.

Even before anyone locks a door, these characters are prisoners of their own secrets. The murder becomes almost secondary to the tension of what might spill out if the truth escapes.

That’s why I believe locked-room mysteries resonate so deeply. They aren’t just thrilling puzzles; they’re symbolic. A locked room can stand in for a mind under pressure, a heart in turmoil, a soul hiding something it can’t bear to confess.

Writers use these physical constraints to heighten drama because isolation removes distractions, proximity amplifies suspicion and conflict, and characters have nowhere to run from each other, or themselves.

When I was writing Party of Liars, I often found myself thinking of my own inner “locked rooms.” The mental places I keep hidden, the thoughts I’d never say aloud. In many ways, my characters became avatars for those thoughts. Because that that’s fictional characters are, aren’t they? Echoes of the conversations we have with ourselves, disguised as people on a page.

It’s why writing a locked-room whodunit can feel so personal. You’re not just plotting a murder. You’re excavating secrets—your characters’ and sometimes your own. And you’re forcing everyone involved to stay in that room until the truth comes out.

Because that’s the real genius of the trope: it’s a pressure cooker for honesty. Eventually, someone cracks. Someone confesses. Someone explodes with the truth they can’t hide any longer. And sometimes, it’s not even the killer—it’s the person who’s been living a quiet life of desperation.

And for the reader, the experience is equally intense. We’re not just detectives trying to solve a puzzle. We’re voyeurs watching people stripped down to their most vulnerable selves. We see the cracks forming, and we wonder: Would I do the same? Could I keep my secrets under pressure? Am I capable of something darker?

Dr. Phil once said his father used to say, “There’s something about him I don’t like about me,” when someone agitated him. It is a simplified version of a quote from the Nobel Prize winning author, Hermann Hesse: “If you hate a person, you hate something in him that is part of yourself. What isn’t part of ourselves doesn’t disturb us.” A reminder that what annoys or frightens us in others often reflects pieces of ourselves.

That’s the secret to a great locked-room whodunit. It’s not just a puzzle to solve. It’s a stage where characters—and readers—project their own fears and secrets onto others. It’s a game of judgment, suspicion, and ultimately, self-reckoning.

A locked room is more than walls and a door. It’s the inner drama we all live out in our heads. And when done right, it’s not just about discovering who the killer is. It’s about discovering who we are. And what might drive us to kill.

(Author’s Note: The term “locked-room mystery” traditionally means an impossible crime—like a murder in a room locked from the inside. Today, it’s often used to mean what was once called a “closed-circle mystery,” where suspects are confined to a specific, isolated setting—a remote island, a cruise ship, or an eerie mansion.)

***