A few times a year, back in the 1970s, my mother and I would take the Greyhound or Trailways bus from Boston to New York to visit my grandparents in the Brighton Beach neighborhood where both she and my father had grown up. The bus station was on St. James Avenue, a cluttered and shabby ventricle close to the dark heart of the city, a long baseball toss from the Public Garden and the exhaust-choked willows sagging into the Swan Boat pond at the corner of Arlington and Boylston streets, and a couple of cut-off throws from the Combat Zone on the edge of Chinatown. The Combat Zone was a concentrated chunk of real estate that housed an array of strip joints, porn theaters, bars of ill-repute and gurls gurls gurls shouted from every squalid bulb-lit, neon fritzing marquee; naked pin-ups behind scratched glass, corner predators eyeing the easy marks like fresh meat. Not exactly the kind of neighborhood you’d leave your child unattended.

On the New York end, the bus route would take us through the Bronx, the borough announcing itself unfailingly with the calling card of a vehicle sitting squarely on its rims, hard by the side of the highway, engulfed in flames—welcome to the Bronx! Similarly, the arrival at the Port Authority Bus Terminal at 41st Street and 8th Avenue brought its own thrills. After all, it was a place described in a 1970 New York Times where “two types of people could be found inside, some are waiting for buses. Others are waiting for death.” Though they left out the pimps waiting for those starry-eyed ingénues from Middle America, those corn-fed easy marks, sad scripts in waiting.

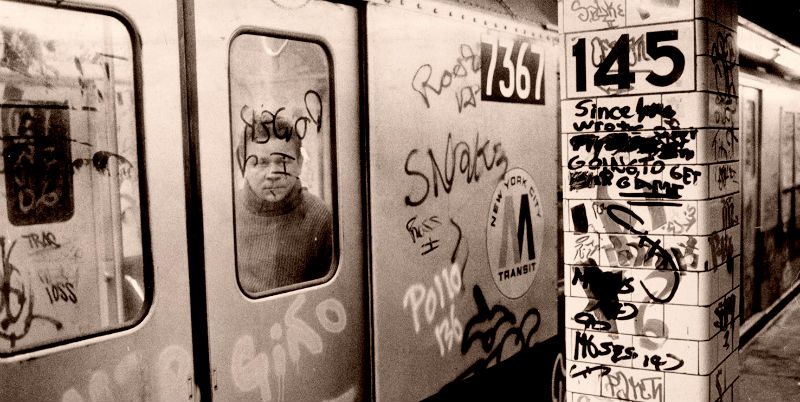

And if the bus station was prose, the graffiti-tagged trains were poetry, colorful, perverse lines stacking into stanzas, sparking and thundering through the rotting Big Apple. The point being, the city was a scary place, a noir character writ large for the writers of crime fiction to draw upon—8 million ways to die in the Naked City—choose one.

As a writer in waiting, I took it all in. The Boston Greyhound station made it into my first novel, Bosstown. As did the once dark corridors of the South End and Boston’s Skid Row along Harrison Avenue, an industrial neighborhood of manufacturing warehouses where Zesty Meyers, Bosstown’s main protagonist, lives in an unheated warehouse loft until he’s forced out by “progress”. Block by block, the gentrification of the South End neighborhood of Zesty’s childhood begins to alienate him. The neighborhood turns—safer, cleaner, whiter—he’s the odd man out. He doesn’t take it well.

Zesty’s not alone. Matthew Scudder, Lawrence Block’s recovering alcoholic and unlicensed PI, limbos through the changing fortunes of his Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood and the Disneyfication of Times Square nearby. Eventually, Scudder vacates his residential hotel, the Northwestern on 57th St between 8th and 9th Avenue, and moves in with his long-time prostitute girlfriend, Elaine, a decision as much about real estate as it is love. If Scudder decides to drink again, he certainly won’t be doing it at Jimmy Armstrong’s Saloon, a steady presence in 15 of Block’s best-selling crime novels. It shuttered over a decade ago. Starbucks got away with the murder.

***

Big-City noir is under siege. As a noir reader, I become as attached to a city as to the main character working those pitiless streets. I tune in for the familiarity or the thrill of a guide who ushers me through the darker alleys of a place I might not venture after dark if I visit in the real world. Think about a novel’s character, it’s not the plot that usually comes to mind, it’s the city or region that they covered. And all the better if the story is someplace we’ve called home or seen in our travels for ourselves. We all conjure our own secret maps of these cities, our own stories and scars, but the gentrification of these places threatens to smooth them all out. That’s what gentrification does, it threatens to render our stories sentimental and nostalgic until we all sound like a lamenting grandparent: back in the bad old days. I’ve caught myself telling these types of stories and the nostalgic tone was not to my liking.

Crime in the big bad city really doesn’t pay. At least not enough to afford the skyrocketing rents.Sure, as writers, we can make things up, but to keep it real in noir as in gambling, the appeal, the thrill lies in that razor’s edge of possibility—big wins, fatal losses. Barring a trip down memory lane, say, a historical crime novel set way back in the 1980s or 90s—those dangerous old days—these high rent-low crime cities pose a major logistical problem for the writer of urban noir; not a warehouse, auto-body shop—the staple of bad guy lairs—that haven’t been converted to luxury lofts, chopped up into condos. Looking for an abandoned waterfront to dispose of that body? Good luck with that. Gentrification is choking the living hell out of noir cities. You need a dirty deed done dirt cheap? Fuggetaboutit. Crime in the big bad city really doesn’t pay. At least not enough to afford the skyrocketing rents.

Back in Robert B. Parker’s Boston where Spenser and Hawk operated, the true predators, it turned out, were the developers with their pitiless wrecking ball eyes and real estate dreams. Beauty, truly residing in the eye of the deed holder. The Big Dig came. The city changed. The Boston of today is geeked out and slick, those South End lofts on Harrison Avenue starting in the seven figures, the streets of this newly designated “historic neighborhood” chock full of high end restaurants, coffee shops, bars, art galleries and boutiques. Gone are the neighborhood boundaries, unspoken but as real as razor wire, the racially segregated, ethnically balkanized neighborhoods that, the borders now blending seamlessly into one another, the only challenge thrown up by the streets coming in the form of a parking ticket.

And it’s not just an East Coast thing either. James Lee Burke’s 1987s Neon Rain describes the pre-Katrina French Quarter in New Orleans as a place where, “the majority of Vieux Carre residents were transvestites, junkies, winos, prostitutes, hustlers of every stripe, and burnt-out acidheads and street people left over from the 1960s. Most of these people made their livings off middle-class conventioneers and Midwestern families who strolled down Bourbon Street, cameras hanging from their necks, as though they were on a visit to the zoo.” Those streets are not so colorful now. Same goes for Raymond Chandler’s sun-blinded streets of Los Angeles, and of whom Ross Macdonald once noted: “He wrote like a slumming angel…” Would that slumming angel even recognize the place now?

So what are we left with? If it’s to be judged by Richard Price’s 2008 killer novel Lush Life, where the high priced bohemia of the Lower East Side meets the “other” East Side of the projects, it’s a facsimile of the dark and original. Berkmann’s, a restaurant featured in the novel is described by Price thus: “Sunlight splashing off of glazed ecru tiles, the racks of cryptically stencil-numbered wine bottles, the industrial-grade chicken-wired glass and partially desilvered mirror…restaurant dressed as theater dressed as nostalgia.” In other words, brand new, trying to look old again for the brand new inhabitants kicking it in this suddenly chic neighborhood. The noir is a thin veneer. Tragedy strikes, of course. It usually does when empty pockets rubs up against new money, but the violence now seems like a bolt of lightning, like a manufactured sleight of hand; painful, sure, but not quite dark enough to qualify as noir.

But don’t cry, noir lovers. Change is cyclical and as long as the slums of the heart keep burning, there’s always going to be material to mine. And as for these newly gentrified cities? The sun will set on them eventually, the cracks will begin to show, the facades will crumble, and the rats will come out to play again. But until then, here’s hoping that stain on the carpet is blood and not cabernet.

***