There’s a reason why media with complex, nonlinear timelines tends to be referred to as “mind-bending.” This was true before we spent 2020 either doomscrolling and Netflixing our brains into mush or squeezing a decade of stressors into a year. But especially now, we can only keep track of so many simultaneous realities at one time without resorting to spreadsheets and diagrams.

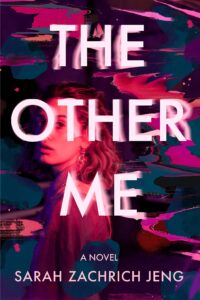

Of course, some people love making spreadsheets and diagrams, especially about the books and movies they consume for entertainment. (If you don’t believe me, do an image search for Inception timeline infographic.) When I was writing my novel The Other Me, I knew I would need to satisfy those analytical readers as much as the ones who prefer to let the story wash over them and have everything explained in the end (for the record: both approaches are equally valid). The main narrative spans just under two weeks in the life of an artist, Kelly, who finds herself plunged into an alternate reality where, instead of going to art school, she married her high school boyfriend. While most of the action takes place in the reading present, Kelly’s overlapping, intrusive memories of her other life make the story anything but straightforward. Essentially, instead of developing one character, I was developing two—one who had moved to the big city to follow her dreams, and another who hadn’t—taking into account the knock-on effects of all the small choices that made up the larger one. This alone would have made those spreadsheets and diagrams a helpful part of my writing process, but—without getting too spoilery—there are other complications in the book’s timeline that made them essential. The Other Me is not science fiction, but the mechanics needed to make sense on an intuitive level, if not strictly on a scientific one. (To any physicists who pick up my book: I am so sorry.)

Writing a novel is hard. Writing one with a twisty or broken structure is even harder. When you think about it, though, most novels have at least some timeline slippage: it’s a rare story that is told straight through from beginning to end, with no flashbacks or deviations. Linearity doesn’t track with the way humans think, which is more like the Internet, with its tangents and rabbit holes. But still, isn’t a linear story a smoother experience, easier, more organized, both from the reader’s end and the writer’s? Why sign yourself up for the extra work of all those additional events and transitions, extra research, and keeping track of which characters know what, when?

Time is a strange concept. It’s supposed to proceed unidirectionally at a constant rate, but our perception of time passing is anything but constant. It dilates and contracts, it slips away when we’re not thinking about it and drags when we are. Anyone who has lived through the past fifteen months knows how weird and woolly our subjective experience of time can get. Our memories are similarly unreliable. Each time we call a given memory to mind, we unwittingly add or subtract details, making it so the episodes from our pasts that we think about most—the ones most integral to our senses of self—may well be the ones we remember with the least accuracy.

If you can evoke this disorderly experience of time and memory, you have a better shot at making your audience feel what your characters are feeling, which is one reason you might choose to chop up your timeline. Christopher Nolan’s films are famous for messing with chronology, but his breakout Memento may be the one that forces us most intimately into the mindset of the protagonist, Leonard. The film has two parallel narratives: one moving forward in time, the other backward. The forward timeline shows a third-person perspective, while the reversed timeline mimics the way Leonard perceives his life. Leonard has anterograde amnesia, which makes him unable to form new memories, and this timeline shows the audience what’s happening from his point of view as he hunts for the man he believes killed his wife and caused his brain damage. This structure gives us a visceral sense of Leonard’s disorientation and frustration.

A writer might also engage in timeline jiggery-pokery to heighten emotional impact, reinforce theme, reveal character, or temporarily conceal information from the reader. Many a twist has been successfully set up by a dual timeline, which allows an author to avoid “cheating” while withholding information (especially when, as in Memento, there’s an unreliable narrator involved). Breaking up the timeline can also let the author reveal a secret—or its significance—that a character isn’t aware of yet. In Margarita Montimore’s novel Oona Out of Order, in which the titular character jumps to a different, often temporally distant, year of her life every New Year’s at the stroke of midnight, the out-of-sequence events seed important clues that things are not always what they seem. Even in a more linear story, a simple flashback can provide plot clues while deepening character. The best time travel or time loop stories have a timely and fresh take on the human condition (Netflix’s Russian Doll, with its themes of interdependence), history (Octavia E. Butler’s Kindred), or current societal issues. In Annalee Newitz’s novel The Future of Another Timeline, for example, time travel is a form of activism. Tess, the central character from one of two plot threads, routinely travels through time both as part of her job as an academic and in her more covert work, in which she attempts to “edit” the timeline to grant more rights to marginalized people. She is part of a circle of women, queer, and trans activists who become aware of another, opposing group literally trying to erase the accomplishments of anyone who’s not a straight white man and lock in a reality where they have absolute power over everyone else. An interesting wrinkle is that only the person who created an edit, and therefore experienced the former, unchanged timeline, will remember how things stood previously. So whenever Tess’s group meets, each member relates their memories of erased timelines, testaments to a history that no longer exists.

These erasures of history have a parallel in the way Beth, the book’s other POV character, is gaslit by her father with an ever-changing array of house rules and unrealistic expectations. Because no one ever calls her father out on his behavior, Beth wonders if she’s the only one who notices it—and, accordingly, whether she can trust her own perceptions. In this way, Newitz ties plot and structure to theme—perception is reality, and memory is a form of history.

With less competent execution, all this jumping around can easily become frustrating. However, a skilled creator can orient the audience without being heavy-handed about it. Montimore and Newitz both provide straightforward chapter subheadings with relevant information (in Newitz’ book, year and location; in Oona, the protagonist’s physical and mental ages). Newitz’s universe also has a consistent if not complete set of rules. Any continuity differences are—or at least could be—the results of edits. On a few occasions, something we are led to take for granted as a “rule” of time travel turns out not to be the case, but this is due to misunderstanding on the characters’ part rather than author neglect. In Memento, one of the film’s great accomplishments is making its structure transparent through its production: the forward sequences are filmed in black and white, while Leonard’s perspective is in color, so we always know which one we’re watching. Between that and some overlap between scenes, most of the confusion we experience is intentional, in that it reflects Leonard’s own.

Such devices are preferable to info dumps in the text (“As you know, Bob, we’re now in the year 2378, and humans’ hands have been replaced with flippers since that ill-advised human/dolphin crossbreeding program we tried back in the 2200s!”) though not always completely necessary. I’m of the opinion that knowing what the hell is going on at all times is overrated. Confusion can be a powerful narrative hook. People love a mystery, and they enjoy being able to look back and make sense of that seemingly nonsensical opening image, even if they can’t immediately put together the entire narrative in order. This is one way stories can reward rereading or rewatching. With each repetition, the audience assembles a little more of the puzzle.

Fiction requires causality, and nonlinear fiction especially needs a heightened awareness of cause and effect because we so often see the latter before the former. If a reader begins to suspect that you, the author, have lost the thread, they’ll stop trusting you. Even if a story is intriguing or stylish enough to keep an audience interested, it still needs to make some kind of sense in the end or it won’t be satisfying. Internal consistency is vital (if your universe requires it). Part of the pleasure of reading a meticulously constructed book like Audrey Niffenegger’s The Time Traveler’s Wife is flipping back through the pages once you’ve finished and noting the ways in which the author has set up her chronology to be stable. The fate of the characters was never in doubt—we just didn’t have the knowledge to see it at the time. Readers will look for significance in every detail, so every detail needs to be significant unless it’s a red herring. In The Future of Another Timeline, the fact that Beth lives not in California, but in Alta California, clues us in from the first chapter that we’re in a universe subtly different from our own.

There are as many ways of writing these stories as there are writers. An author might write each timeline chronologically and independent of the others, then tear them apart as needed. Or they might jot down scenes as they occur and make them fit together coherently in revisions. Consistent and predictable rules help keep things straight for the author as much as the reader, but characters have a way of not following the rules, and it’s up to the author to make sense of the mess left behind. Note cards, spreadsheets, scribbled charts, project management software, 3D mind maps—all tools and processes I used or considered while writing my own novel. (Having enough space for a serial killer-esque book ideation room is, alas, still a dream.)

Whether your system is organized or disjointed, the same tenet holds true as for any story. Believe in your characters. Readers—most of them, anyway—will suspend their disbelief and remain invested as long as they care about the people whose stories they’re reading, and you don’t mess up too much.

Why are we so fascinated by stories that play with time? We read fiction to get into other people’s heads as well as learn more about ourselves; maybe we’re looking for a lifelike window into another mind or searching for that elusive mirror to our own experience. We might be hankering for a puzzle that intrigues and mystifies us, then lets us feel smarter when we guess where the clues are leading. Or maybe we simply wish to escape, at least for a few hours, into a universe where events might not be as irreversible as they are here. Where the past might be as changeable as memory itself.

***