Many years ago, my uncle, Clinton Barbra, looked out his front window and saw a police car idling at the end of his driveway. The car sat there for a moment, and then pulled away. My uncle ran out the back door of his house, went into the trees, and started pulling apart his still.

The squad car was driven by a friend of his at the station. That little pause by the driveway was the tip-off: the cops were on their way. My uncle hid what he could in his attic. He couldn’t hide the barrels of mash, however. The police arrested Clinton and poured kerosene over the barrels. When his wife bailed him out, he went back home, dipped out the kerosene, reassembled the still, and ran another batch. After all, no use letting it go to waste.

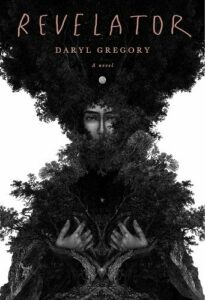

My uncle told me this story a couple years ago as we sat around his kitchen table in Rocky Branch, Tennessee. I was writing a book in which the main character is a moonshiner, and I was pumping him for details. His sister, my very Baptist mother, kindly tolerated us sipping white lightning while we talked distillation methods and recipes.

Whiskey runs in both sides of my family, the Barbras (everybody down south just called them “the Barbs”) and the Gregorys. My dad used to say there were two kinds of Gregorys, the preachin’ Gregorys and the whiskey Gregorys. If you hike into Cades Cove, part of the Great Smokey Mountain National Park, you can find Gregory Cave, where my ancestors reportedly kept a still. (You can also hike up Gregory Bald, the mountain named after my great-great-great-grandfather, Russell Gregory, but I advise you to be sober for that strenuous climb.)

Turning corn into moonshine made a lot of economic sense for early American farmers. First, liquor was a durable storage medium; whiskey doesn’t rot. Second, it was an excellent transportation medium. The liquor one horse could carry was worth 20 times what it could carry in corn, and the nearest market for Cades Cove farmers was Knoxville, forty miles northwest.

Selling your own moonshine was also legal in America—until 1791, when the new government first tried to tax whiskey. Farmers weren’t happy. President George Washington managed to put down the Whiskey Rebellion with the aid of 15,000 militia, but untaxed whiskey continued to be sold. Tennessee outlawed the manufacture of whiskey entirely in 1878, which only increased homegrown production. Cades Cove was home to a couple large distilleries, well known for their brandies. A newspaper article described a police raid on one “rum-mill” run by George W. Powell. The nine-man “revenue squad” seized 11 tubs of mash, 130 gallons of “singlings” (brandy that had only been distilled once, rather than the usual two times), and bushels of meal, rye, and malt. They also arrested Powell, who “subsequently escaped, while the men and women of his household were abusing and threatening the officers.”

Prohibition made a lot of moonshiners rich, and bootleggers, too. (Some definitions: Moonshiners make the hooch, and bootleggers, who got their name in the 1880s from men who tucked flasks into the tops of their boots, smuggle it.) Those 1920s bootleggers started souping-up their cars to outrun the cops, and some of those daredevils became early stars in NASCAR.

Even after Prohibition was repealed in 1933, moonshining continued, because it was good money. Not easy money, though. Uncle Clinton said the work wore him out. He’d come home from his day job and make whiskey all night, prepping the mash, getting the still up to temperature, keeping the process running, and then proofing the results. His mash recipe included 60 pounds of sugar per barrel (people at the grocery store would look at him strange when he bought so many bags at once), 50 pounds of rye, and malt. He made the malt himself. He’d wet down shelled corn, cover it with a tarp, and when it sprouted, let it dry in the sun before he ground it up. He’d mix the corn meal, malt, and sugar with water, let it ferment for twelve hours, and then “cap” the barrel with raw rye. In a few days the mash would ferment into a soupy, yellow distiller’s beer.

When it was time to make a batch, he’d pour the beer into the pot and start it cooking. The pot was usually made out of copper and held 100 or 200 gallons, but if you could work with galvanized steel, you could go bigger. My uncle once ran an 800-gallon steel beast fired by propane.

That still was long gone by the time we had that talk in his kitchen, but he showed me a little hand-welded model of a still and talked me through the process. Alcohol fumes from the boiling pot travel through a pipe (called the arm) to a thump keg, a smaller container partially filled with distiller’s beer. The hot pot fumes mix with the cooler beer fumes, providing a quick, second distillation. The fumes then move through a crossover pipe to the flake stand. The flake stand is a barrel kept full of constantly running creek water, with a copper pipe winding through it. The fumes condense into liquid and run out the bottom of the stand through the tail of the pipe, called the worm. It was common for moonshiners to set the penis bone of a raccoon inside the lip of the worm to help it run cleanly into the catch pan. (Some details, while not integral to the distillation process, are essential to the fiction-making one. The raccoon pecker made it into the novel.)

Then came the proofing. That afternoon my uncle took out a plastic milk jug half full of moonshine and showed me a simple but mystifying way to check the alcohol by volume: just shake it. He could judge whether the proof was low or high by the size of the bubbles—a big bead meant you were hitting your target, which was usually around 110 to 115 proof.

But even after you’d distilled your jugs of moonshine, you still had to sell the stuff without getting caught. A major problem was who to trust. You couldn’t let people know where your still was, or let too many people know who was making the hooch. My uncle had to stop working with a partner who couldn’t keep his mouth shut; he kept bragging about how good their whiskey was. That meant that sometimes Clinton was his own bootlegger. A few of the stories he told me about that afternoon were about close calls with the police while he was making deliveries, like the time he had to smile his way through a police checkpoint with just a tarp covering a load of moonshine in his truck bed.

My uncle had to hide his activities from his family, too. His father had been deputized to hunt down moonshiners, and family lore is unclear on when, exactly, he found out his son was making whiskey. I was just glad I found out in time to get his recipe and methods into my book. (Writers are selfish that way.) Clinton’s in his eighties now, and he insists that he’s retired. But that afternoon in his kitchen I wondered, if he’s retired, why is there so much fresh whisky in his kitchen?

***