Which of us didn’t wish, as a child, that we might be invisible for the day? What fun we might have had: eavesdropping on the adults, sneaking into rooms where we weren’t usually welcome, standing behind teachers as they wrote questions for the next day’s test. I never did get to click my fingers, disappear from sight and walk unseen into Buckingham Palace but, now in my fifties, I have finally become invisible, just as my older female friends always promised I would.

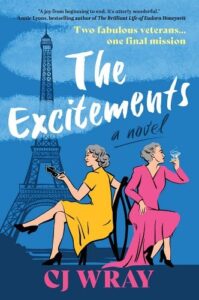

The sister heroines of my novel, The Excitements, are ninety-something WW2 veterans Penny and Josephine Williamson. Thanks to their age, both are well used to being overlooked (and patronized) but, rather than bemoan her fading from view, 97-year-old Penny uses the fact that nobody particularly notices her to great advantage. She’s a jewel thief and a very successful one at that. After all, who would believe such a sweet little old lady could ever be ripping them off?

Extraordinary as the thought of a jewel thief well past retirement age might seem, the fictional trope actually has a number of real-life precedents. There are plenty of examples of women who have pulled off the most audacious crimes using only their advancing years—and perhaps the fact that they are female—as a disguise that renders them practically unseen.

‘Diamond Doris’ Payne began her career as a jewel thief in the 1940s, posing as a wealthy young heiress as she bamboozled jewellers all over the United States. Her method relied on not seeming like the kind of person who needed to steal anything. She’d have jewellers show her dozens of jewels at the same time, keep them distracted with small talk while she pocketed one or two, then hope that nobody wouldn’t miss the gems until she’d made her getaway. In the 1970s, she used this method to steal a 10-carat diamond ring valued at some $500,000 from a jeweller in Monte Carlo. Though she was arrested and held for nine months, the ring was never recovered.

Payne was always one step ahead of the police. She was prolific, using at least thirty aliases and stealing gems all over the world. In the 1980s, she managed to escape custody by faking an illness that required a hospital visit, making a dash for freedom while she was supposed to be languishing on a ward.

Payne was still tormenting the luxury goods salespeople of the United States well into her eighties. She stole a $22,500 diamond ring at the age of 83. For that she was sentenced to two years in prison, but released after only three months. Though her sentence also required that she not go near a jewellery store again, she’s believed to have lifted a ring worth more than $30,000 dollars from a store in North Carolina less than two years later, aged 85. Payne claims to have retired now but when she was asked if she regretted her life of crime, she said, ‘I don’t regret being a jewel thief. Do I regret being caught? Yes?’

Doris Payne is such a legend, that her life has been made into a movie. But even her $500,000 Monte Carlo heist raised small change compared to a heist pulled off by sixty-year-old Lulu Lakatos in 2016. Posing as a gem expert, Romanian-born Lakatos made an appointment at the Mayfair branch of high-end London jeweller Boodles, claiming to have been sent to value seven gemstones on behalf of a wealthy Russian buyer.

In the store’s ultra-secure vault, a member of staff showed Lakatos the gemstones, which were kept in a padlocked pouch. Somehow, in a matter of minutes, Lakatos managed to slip the pouch into her handbag, swapping it for an identical pouch full of distinctly un-precious pebbles. No-one noticed the switch until the following day, by which time Lakatos had passed the diamonds on to an international criminal gang.

At her trial, Lakatos was unkindly described by the Boodles chairman as ‘most unattractive’ and ‘dowdy and plump’. Found guilty, she was sentenced to five years in prison and required to compensate the jeweller for the diamonds, which have never been found. She was ordered to hand over everything she had to her name, which was, at the time she was arrested, less than £250.

It wasn’t the first time Lakatos had pulled off such a stunt. In a previous incident she managed to switch an envelope full of pieces of plain paper for an envelope containing $400,000.00. Unattractive as the Boodles chairman claimed she was, there was obviously something quite distracting about her. Perhaps the chairman nailed it when he claimed that the only thing he could recall about her appearance was her ‘enormous boobs’.

The wider picture of criminal activity in old age is far more poignant than thrilling. Japan was among the first countries to notice an uplift in theft by the elderly—particularly elderly women—while overall crime rates were dropping. An investigation into the motives of those arrested revealed a cohort of senior citizens so battered by the cost of living that going to jail seemed like a good way to escape the problem of ever spiralling bills. Shoplifting was the perfect crime, with no violence required but the promise of a short custodial sentence in the warm as ‘punishment’.

With the cost-of-living crisis, similar stories are becoming more common in the United Kingdom and the United States, though it’s doubtful that many elderly criminals in the UK or US are hoping to end up in prison for the winter. More likely they’re just hoping to shave something off their grocery bills. It’s a far cry from the glamour of Diamond Doris or the daring of Lulu Lakatos. But the antics of Payne and Lakatos do show us one thing: we underestimate older women at our cost. Ignored and unremarkable—at least in terms of appearance—some of them are busy taking advantage of the fact that they don’t stand out. It seems that in the right circumstances, the invisibility younger women are taught to dread, might turn out to be a super-power.

***