The first adaptation of Dracula was technically released even before the novel was.

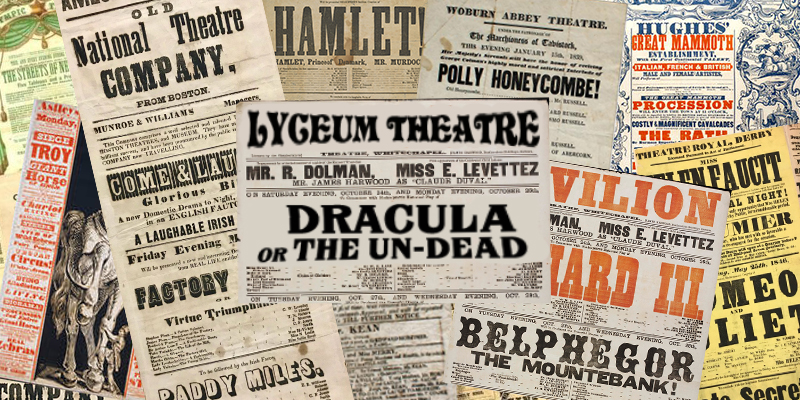

Eight days before the novel Dracula first went to sale in 1897, the Lyceum Theatre, the famed institution for which Bram Stoker was the business manager, performed a theatrical adaptation that Stoker had written himself. Sylvia Starshine, the editor of the play’s first published edition, suggests this was to protect against unlicensed theatrical versions directly adapting the novel, profiting from the ideas; if anyone did write a similarly-themed vampire play after Dracula hit the bookshelves on May 26th, he could then bury the other work on the grounds of copyright infringement.

This was a good instinct; the early history of Dracula is rife with pirating attempts, the most famous of which is F.W. Murnau’s seminal 1922 film Nosferatu, against which film Florence Stoker, Bram’s widow, began a ten-year copyright battle and the film that resulted in her licensing many adaptations, including two plays and the Universal Studios film. And there were other pirated versions and adaptations fro around this time: in 1917, an unauthorized stage version of Dracula appeared, as did, in 1921, a similarly unsanctioned (and probably lost) Hungarian film called Drakula Halála, or The Death of Dracula (it seems that Mrs. Stoker never came across this film version). And in 1925, Aaron Copland and Harold Clubman drafted an opera called Grogh, based on Murnau’s Nosferatu.

It is prescient then, how, in 1897, future theatrical piracy of his novel was on Stoker’s mind. On Tuesday, May 18th, 1897 (at 10:15 am), performed a theatrical adaptation of the yet-unpublished novel that Stoker had written, himself. It was only performed once. And, well, it seems to have been more of a reading. A stage and lighting crew are not recorded as having been used. Only front of house staff were hired. Junior members of the Lyceum Theatre company were hired (as they were already on the theater’s payroll, they did not require additional payment). The most famous member of the cast is the actress who played Mina: Edith Craig, the daughter of famed 19th century stage actress Ellen Terry and the older sister of the architect Edward Gordon Craig. Edith, a talented actress and passionate suffragette, would have been the ideal embodiment of the very modern Mina.

Starshine concludes from surviving Lyceum Theatre records that the play was not intended to sell tickets (just enough, to friends and company members, to fulfill the audience quota that would constitute “public performance” enough to receive the copyright. After that performance, it was filed with the Lord Chamberlain’s Department (pursuant to the Theatres Act 1843), and forgotten about. That copy is the only one that remains.

Starshine hypothesizes that Stoker wrote the play very quickly. Giant monologues are full of exposition, and whole chunks of the novel’s text appear in dialogue; it is, simply, a very faithful adaptation, and, as a result, a very bad play.