When I couldn’t see my youngest for two years because we were in a global pandemic and she lived on the other side of the world, I had to find a way to endure it. What other choice did I have?

My partner Karyn and I live in Santa Cruz, California. Our daughter, Eliza, lover of languages and travel, resides in Amman, Jordan, 7500 miles away.

When your child lives ten time zones away, you get a crash course in separation. I learned to shelter my emotions and look on the bright side: our daughter was living her dream. She was 24 years old. Independent. Doing what she loved: living in another country, speaking fluent Arabic, working with refugees. She’d met a Jordanian man and fallen in love. We’d met him. We liked him. Our daughter was happy. We were happy for her.

We grew accustomed to having a child on the other side of the world.

But then the world changed.

When Italy was overrun with Covid in early March 2020, I had to cancel the writing retreat I’d been set to teach in Tuscany that spring. My plan to meet Eliza there, and then to fly on and visit her in Amman, had to be scrapped, too. Her planned trip home for her brother’s wedding two months later became an impossibility. The wedding happened, pared down to ten masked guests in our backyard, but Eliza wasn’t there.

She was hunkered down in Amman. We were hunkered down in Santa Cruz.

I’d always known, from the time she fell in love with languages—Spanish in grade school, French in seventh grade, Arabic in high school—that Eliza was going to be an international person, a person of the world. As her parents, we supported that. When she wanted to study Arabic at fifteen, I found her a tutor. When she won a spot in a State Department program for teenagers to study impacted languages in Morocco, we sent her with our blessings. Our decision to champion Eliza in fulfilling her dreams superseded our desire to keep her close by.

I told everyone who asked that I was fine with my daughter living and loving and working across the world. And most days I was fine with it. I looked for the silver lining in the immense distance between us—the wonderful trips Karyn and I got to take to the Middle East to see her—the countries we traveled to, the people we met that we’d never have met otherwise. The way Eliza opened up the world for us.

And God forbid, if something terrible ever happened, we could always hop on a plane and get to each other. Long gone were the days when the only communication between parents and a child living overseas was a thin blue airmail envelope crammed with miniscule writing. We lived in a global community now. Technology and air travel had shrunk the distance between us. We had WhatsApp, Facebook messenger and Skype. We could communicate with Eliza anytime, for free. She was just a plane ride away—well, a couple of plane rides away.

I never imagined a day when we couldn’t visit her, see her, or hug her, when we couldn’t take a walk together or simply breathe the same air.

Until the virus came.

In those first surreal months, we compared notes with Eliza about our differing pandemic experiences. In the U.S. we were social distancing—something that never happened in Amman. Karyn and I were fastidiously disinfecting our vegetables and quarantining our mail. Jordan’s borders were sealed. In Amman, people were banned from leaving their houses for days at a time—violators could be arrested. Eliza was only permitted to walk and shop in her own neighborhood—cars were prohibited. When we called her, she’d often be up on the roof, the only place she could “get away,” watching colorful kites soar through the air. Kite-flying had become a Jordanian obsession.

We established a family text thread on WhatsApp. Met on Skype for cooking parties: me and Karyn in Santa Cruz, Eliza and her partner in Amman, our son and daughter-in-law in Boston. We all cooked together—with one of us taking the role of lead chef—the resulting meal would be breakfast for us, lunch in Boston, dinner in Amman. Making food together across ten time zones helped us feel connected.

As the months wore on, I missed Eliza, and dove deeper into my own life. I finished the memoir I’d been laboring over for ten years. Eliza, who’d already read an earlier draft, offered to critique it a second time. She emailed back the manuscript filled with skilled edits and entertaining margin notes: “God, Mom, I can’t believe you actually said that to Grandma.”

Every time we Skyped, she asked, “So Mom, how’s it going with the book?”

Once Karyn and I were fully vaccinated, in May 2021, Eliza told us that she wanted to come home for a visit. I wanted her to, of course, but I only allowed myself to be cautiously optimistic. I didn’t let myself feel it, not really, because of how unpredictable life had become. Flights could be canceled. Borders closed. New variants could arise. Tamping down expectations for the future had become a habit, a way of life. So, I didn’t let myself feel joy or anticipation about her end-of-summer visit. I focused on my work and our new pandemic puppy. I lived within the small footprint of my life at home.

But then Eliza got vaccinated. Bought a plane ticket. She emailed her itinerary and I put her arrival date on the calendar. As tomatoes ripened in the garden and the day grew closer, I still didn’t let myself feel it. Not really. Not until the week she was scheduled to arrive.

Eliza flew from Amman to Boston to see her brother and her old friends from college first. Now we were only separated by three time zones, her first visit in two years just days away. I started texting with her about the food she wanted us to have in the house, and that’s when I let the drawbridge down and finally allowed excitement and anticipation to explode in my body.

Our girl was coming home.

At 8:00 AM on the day of her arrival, Karyn and I drove to the San Francisco airport—and joy of joys—we weren’t restricted to parking in the cell phone waiting area. Pick-ups were no longer limited to curbside; we could actually go into the airport to greet her. We arrived early, parked the car, found her arrival gate, played three hands of 500 Rummy to pass the time. We made melds and kept score on a napkin. Karyn and I didn’t talk about what was about to happen. It was too big.

And then there she was, framed by the arrival gate. As soon as she saw us, she rushed over. Hugged Karyn first. Then me, and then all of us in a three-way squeeze, the press of our bodies making our reunion real.

Through the terminal and down to baggage claim, we talked. About her flight. Her visit to Boston. Her partner in Amman. The whole time I just kept staring at her. Drinking her in.

Our daughter was no longer virtual, no longer just a text message, a still photograph, a flat face on a screen. She had length and depth and substance. Her skin was soft. She was three dimensional. I could smell her shampoo. Eliza was real.

We drove the long way home, down the coast, so she could revel in the Pacific, the windsurfers, the stunning coastline. I savored every moment.

When we pulled up in front of the house that she’d grown up in, Eliza lugged her suitcases inside. She met our puppy and the three of us had lunch out in the garden, surrounded by Karyn’s beautiful flowers.

Then Eliza said, “Come here, you two, I have presents for you.”

She gave Karyn a beautiful weaving, handmade in Jordan. Karyn had been a weaver for years. She loves textiles; it was a perfect gift.

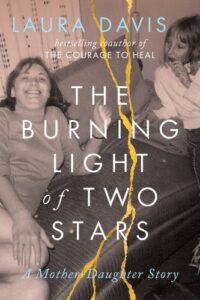

Then Eliza handed me a rectangular sheet of paper filled with flowing Arabic calligraphy. The intricate design was beautiful, but I had no idea what it said. “Mom,” she explained, “it’s the cover of your book in Arabic. Your first foreign cover. This is the title,” she said, pointing to some beautiful squiggles. “Right here, it says, The Burning Light of Two Stars. She slid her fingers further down the page. “Here’s the subtitle: A Mother-Daughter Story.” Then she moved her pointer finger again, “And here’s your name and the publication date.” When I took a second look, I could see how carefully the calligrapher had integrated the visual motif of my book jacket into this remarkable piece of art.

I took it in my hands and cried. I cried because of everything embodied in this gift: Eliza’s love, her care, the way she saw me. I cried because she’d sought out the perfect Arabic calligrapher to create this gift that would only have meaning for me. She and her partner had searched all of Amman looking for the exact right shade of blue ink to match the accent color on my cover. She’d found a way to carry this piece of art flat across the world to hand it to me. She’d made my book international before it was even published. But most of all, I cried because my daughter, the one who loves and embraces the great vast world and all the people in it, was finally home.

***