In the early twenty-tens, I read Albert Camus’ The Plague. Due to its allegorical treatment of the French Resistance to Nazi occupation during WWII, it reminded me of the current gentrification resistance movements popping up all over Los Angeles. At the time, I lived in South Central, although urban planners and city leaders attempted to rebrand it as South Los Angeles in order to liberate it from the negative stigma it developed in the 80s and 90s in relation to: the crack epidemic, gangster rap, street gangs, graffiti, and social-realist urban films. But of course, a simple name change cannot delete a region’s past. Yet, in a city like Los Angeles, where culture is driven by constant reinvention, it is not unusual. Chinatown was once Sonoratown because of all the Mexicans who lived there, and Little Tokyo was once Bronzeville, to accommodate the Blacks, Native Americans and Mexicans that lived there during Japanese internment. It went back to being Little Tokyo when the Japanese community returned.

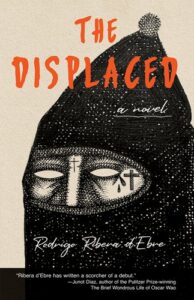

I did not want to live in South Central, but I couldn’t afford a house in the LAX coastal region of Westchester, Playa Del Rey, or Culver City, places I considered home. I kept thinking of Camus’ coastal city of Oran, a Mediterranean location in Algeria, as the place for his plague battleground, and I assumed that the newly rebranded “Silicon Beach” ―the Westside of Los Angeles―along with its perennial Mediterranean comparisons, was the appropriate location for an end-of-the-century conflict. The media didn’t talk as much about the street gangs that plagued the region back in the 80s and 90s, which was the reality I lived through and participated in. These social ills were already considered “old school.” The new conversation was centered on urban renewal, open-space design, the tech industry, development, and displacement, and it was this phenomenon that directly led me to write The Displaced.

Similar to Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent, I focused on place as a form of characterization. The Independent called Conrad’s ignored London location “a great city novel,” and I too attempted to give voice to an overlooked area―the Del Rey neighborhood and the Mar Vista Gardens Housing Projects. I wanted the community to resonate, before it becomes erased and white-washed by renovation. Moreover, I wanted to position the reader at the end of the millennium where fear of change, Y2K and lack of education contributed to a bleak point-of-view. A time when collective, doomsday apocalyptic stress took over rationality. All over America, people started militias, packed garages and basements with water and canned foods, armed themselves, and looked to God for answers. It is in this absurdist thinking―in the face of powerlessness―that the novel exists.

Residents in disenfranchised neighborhoods could never have imagined the concept of gentrification. Even though our people have experienced drastic forms of social disorganization in this city; from redlining or being excluded from buying homes via housing covenants, to our streets being gutted for infrastructure projects, a return of the gentry was out of focus. White flight created a form of abandonment all over Los Angeles, as a result of suburbanization and freeway expansion of the 1950s, and my attempt was to draw out the marginalized Del Rey neighborhood and the projects, as a statistically significant sample, which can be used for gentrification comparisons. Today, homes near the Mar Vista Gardens Housing Projects sell for millions of dollars, which is clear that working-class people from the area can no longer afford a house where they grew up. Once considered one of the most poverty-stricken communities of the Westside, Del Rey is now a cool and hip zip code located in thriving Silicon Beach.

Similar to Camus’ The Plague, I chose a reporter―someone who attempts objectivity to such a marvel―as a main character. It is a coming-of-age story, and his arc goes from student, to writer, to distinguished journalist. Mikey Bustamante is deeply rooted in the community of Del Rey, but he lives just outside the projects, home to the notorious Culver City 13 gang. While examining this character’s undertaking, I looked toward Black writers to help in my understanding of America’s larger race conversation. Chester Himes’ If He Hollers Let Him Go and Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man were a source of inspiration. The bigger question was how to present Americanness, while also stressing Otherness. Is Mikey American enough? Can America see themselves in him? Will people of Mexican descent identify with his struggle? In the opening chapter, Mikey is called out on his dress style, appearance, and interests, and he is accused of being White-washed. Thus, Mikey Bustamante must learn to navigate the resistance while doing his job. He does not entirely fit into the larger Latinx community he is surrounded by, yet he is not at home with his White counterparts. This theme is presented throughout the novel as a way to abandon identity politics, yet still make it about identity.

In Himes’ book, his main character is a fractured existentialist who is staunchly anti-White, while Ellison’s underground, or invisible man, exercises power through his opaqueness. In The Displaced, Mikey is neither opaque, nor invisible, nor anti-White. Unlike Ellison’s invisible narrator, or Himes’ overtly Black and angry protagonist, Mikey reflects the status-quo back to those who make up the new gentry. Mikey’s characterization is deliberate, in order to present a more nuanced approach to race, class, and conflict, which examines what Robert Wuthnow maintained: “A single work of art or literature that affects the social order must relate closely enough to its social environment to be recognizable, yet maintain relative autonomy from it.” The goal is for Mikey to be close enough to be affected by the problem, while also disengaging from it as a journalist.

The Displaced is also an examination of the human condition. The characters in the novel must reconcile with universal themes like religion, myth, murder, betrayal, goodness, suffering, groupthink, and others. The struggle against urban renewal in the book mirrors today’s dialogue about whitewashing and cultural appropriation. More than ever, people of color are fighting back to reclaim what has been stolen from us. Museums, publishers, galleries, music studios, television series, and films, are under attack for their lack of diversity and authenticity. Historically in American literature, White writers often introduced lowly-developed, moronic, buffoon-like, exotic and folkish “other” characters. Sometimes they didn’t give the characters a name, and simply wrote things like the Jap, the Negro, or the Mexican. When writers of color, starting with the Harlem Renaissance, introduced characters that were complex and multi-dimensional, they began to give life, meaning, and understanding to the marginalized other. These writers claimed that American nationalism, identity, and culture cannot be examined without taking into consideration the contributions of “other.” Simply put, readers do not want to read about themselves through an outsider’s perspective. They do not want to read assumed voices for the sake of messaging, human understanding, solidarity, or whatever other justification they might claim. In The Displaced, a White novelist who is interested in writing about Mexican American gangs (because he thinks it’s cool and interesting) is murdered by the resistance for his audacity. On the streets, situations are handled differently.

The goal is for readers to be aware of the serious repercussions caused by gentrification. For powerless people, community is all they have. In wealthy neighborhoods, housing associations and neighborhood council groups thwart development and radical zoning, but in working-class areas, this is often out of their control. I want to place the reader in their situation, as if they too were cornered and they had nothing else to lose. For people like my characters, home and the hood are everything, and if that is taken from them, people will respond in unexpected ways. The people in the novel are people you see and who surround you daily. They cook your food, wash your car, clean your house, and take care of your children. Simultaneously, they are your council members, police officers, assemblymen and women, professors, gang members, artists, lawyers, and architects. They are Los Angeles.

I turned this novel in as my final thesis for my MFA program at Mount Saint Mary’s University. Two years later, I was still getting rejection letters from publishers and literary agents. However, at the beginning of the Covid-19 Pandemic, with the lockdowns, quarantines and riots, themes I had written about in The Displaced, it occurred to me that the novel might have more significance. Not surprisingly, Penguin Classics reported that Albert Camus’ The Plague became a bestseller in 2020. I decided to send my work out to the world again, and publishers and literary agents that had ignored me in the past, suddenly seemed interested. I signed on with the University of Houston’s Arte Publico Press because they showed more care and understanding of my work, formerly titled, The Plague @ Silicon Beach, as a nod to Camus. The whole world has changed now and we are still in the midst of the pandemic, and somehow these worldly plague themes are as relevant as ever. Yet, we are still powerless, and our absurdist thinking is the same, whether fact or fiction.

On a final note, I no longer live in South Central Los Angeles. I moved to the affluent suburbs of the Palos Verdes Peninsula, and according to some elderly White neighbors, we are the new gentrifiers in the neighborhood―young, different and other. It occurred to me, for the first time, that the face of gentrification is not the same everywhere.

***