No pain, no gain! A common refrain, and the quintessential mantra of those who hustle. While you’ve probably seen this couplet superimposed over dozens of muscular athletes wielding barbells like feathers, there are much smaller, quieter examples of pain as the pathway to a different type of success: healing. Very few people can put in an intense workout and escape the painful bodily backlash the next day, and the process of healing is no different. Trauma hurts and so does banishing it.

I write about trauma because I am intrigued by how much our pain shapes us, and by the overall resilience of the human spirit. While the biggest examples of this are usually seen in news stories of miraculous survival, it’s not necessary to go through a life-changing event in order to be hurt. Core memories can be created by something as simple as a painful word spoken by someone you love, filed to a point sharp enough to poke at you your entire life.

There is no such thing as a trauma-free life; we are all the result of our reaction to pain and our ability to deal with it. But when it comes to severe trauma, the consequences of avoidance can be devastating. Some people are able to break the cycle of abuse by appreciating the pain it caused them. They strive not to hurt someone else the way they were hurt—even though they might want to. But in far, far more cases, another adage is true: hurt people hurt people. Many people who have endured severe pain feel entitled to inflict it on others—they may enjoy it. In recent years, bullying has extended way beyond the playground, and we have the videos to prove it: three-minute snippets of miserable people inflicting misery on others.

While I find damaged characters the most compelling to write about, one troubling aspect of doing so is that in order to show their growth and their arc, you have to keep hurting them: again and again and again. And that’s because retraumatization—facing your demons when they show up—is a major part of healing.

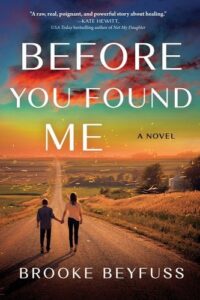

In my new novel, Before You Found Me, my goal was two portray two characters with extremely traumatic backgrounds, and to craft a unique pathway to healing for each, demonstrating how personal and painstaking the journey can be. There’s Rowan, a twenty-two-year old woman who narrowly escaped death at the hands of her ex-fiancé, and Gabriel, an eleven-year-old boy who has spent the last three years held captive in a basement by his grieving father. Fresh off her own trauma, Rowan discovers Gabriel trapped in his basement: beaten, starved, and convinced he deserved nothing more. With an all-too-intimate understanding of the failures of the legal system, Rowan acts in haste and desperation, snatching Gabriel from the dark and taking him halfway across the country for a fresh start; a beautiful, pain-free life for both of them.

I wanted to create arcs that demonstrated the importance of support, but also showed the strides the characters took to change their own lives. Being young, naïve, and damaged herself, Rowan is deeply flawed, yet heroic in her actions. After abducting him, Rowan bubble-wraps Gabriel into a new life, leading him toward a real future on a path lined with bright and shiny things. She showers him with the comforts he’s long been denied, offers endless support and golden opportunities—anything that will stop him from looking behind him.

Spoiler Alert: It doesn’t work.

In an effort to avoid retraumautizing Gabriel, Rowan denied him the opportunity to process his anger and grief and truly heal. No pain, no gain, right? A major part of the healing process involves learning how to acknowledge and work through trauma rather than repressing it or acting out. Because she is young, hurt, and vulnerable herself, only a tiny part of Rowan realizes this—so tiny it’s easy to ignore.

In developing traumatized characters, there is no standard blueprint to follow. Trauma usually has a domino effect, with one event often leading to another. Relying on the commonalities of fear and anxiety is impossible because trauma does not affect people in the same way—it’s deeply personal. But one shared trait is the ability to mask trauma and seek out distractions. While this can look like healing, it’s just the opposite. Trauma is like a sponge, and ignoring it is like sticking that sponge in a glass of water. It’s only going to get bigger. The fact that so many people choose to do just this is a huge testament to the pain of retraumatization. When you choose to face your demons, you do so prepared to fight. But when your demons suddenly face you, it’s all too easy to be overcome.

Like trauma, we all have flaws in our thinking, and my favorite flaw is an overflowing heart. A person who feels so deeply for another that they’re willing to sacrifice their own safety, their own happiness, their own life, for the benefit of someone else. That’s what I found in Rowan. But the best of intentions aren’t always so, and in writing this book, I discovered that right alongside my characters. It was important for me to allow them to confront their own demons on their own terms because no matter how much it hurt, they came out far stronger on the other side.

***