The scariest part of a horror story isn’t always the monster. Sometimes, it’s the person who props the door open and says, “Come on in.” Worse still? The one who looks you dead in the eye and says, “This is fine”—or shrugs and mutters, “Okay, this is bad, but fixing it would be hard. Let’s just see how it plays out.”

There are levels to this kind of apathy, and every one of them is dangerous in its own dark and twisted way.

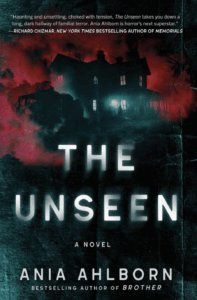

In my most recent novel, The Unseen, a grieving mother named Isla brings something unnatural into her home after losing a pregnancy. When a little boy, Rowan, appears in the trees just beyond her house, she treats him like a miracle. A cosmic do-over. Maybe even a gift from God, which her husband, Evan, finds utterly baffling, considering Isla has never been one for religion or faith. One look at Rowan and Evan immediately knows that something is off. Their kids know, too. Sophie, the youngest at five, is the first to say it out loud: That kid is scary, and I want him to stay far, far away. But Isla won’t hear it. She can’t hear it. Because if she does, she has to let go—and she’s not prepared to do that. Not again.

So, they let Rowan stay.

It’s a decision that tears the Hansen family apart.

Like so many, I know a version of this story. I’ve seen it play out up close and personal, and I’m still living in the shadow of it today. Grief can consume a person so completely that they forget who’s still standing beside them. They turn inward. They stop being a parent, a partner, a functioning part of the family. And the people around them are forced to wait, or to flail helplessly, breaths held. They try to be patient, try to find ways to help, but there’s only so long they can live in the shadow of someone else’s pain, and sometimes the person at the heart of it all isn’t interested in help anyway. They don’t want to move forward, don’t want to claw their way out of those despairing depths. They want to stay exactly where the pain is sharpest, because for them, that’s where it feels the most real.

And that’s not fiction. That’s today, happening to a real family at the end of your street. Sometimes all it takes is one refusal, one silence, one moment of looking away for the whole house of cards to collapse. And sometimes, the house collapses before those inside ever realize the walls are coming down.

But that’s the thing with domestic horror. It doesn’t need made-up monsters. It just needs someone to stop trying. Often, that someone is the mother. But sometimes it’s the only person who might’ve been able to pull her out—a spouse or close loved one, a last line of defense.

This type of horror doesn’t wear a mask. It walks around in daylight. These are real mothers, wrapped in grief or conviction so thick it becomes its own reality. Some of these women keep their families on emotional lockdown. But tragically, some take them out completely. And this is a story that’s becoming more and more commonplace.

In 2001, Andrea Yates drowned her five children in the family bathtub. She had postpartum psychosis, a long history of mental illness, and every warning was flashing red above her head like a neon sign. Her husband and doctors knew she was struggling, but they did nothing to help her. Instead, Andrea was pushed to have more children, pushed to make a fresh start, and pushed to normalcy, as if willing it hard enough into existence would make it true.

It did not.

There’s horror in what she did, of course, but also in what the people around her failed to do. Everyone kept going. Everyone stayed quiet. Everyone put the responsibility of making it fine onto Yates’s shoulders. But it wasn’t fine. It was far from it.

Lori Vallow is another tragic name in a similar scenario, though she took a different route. Here, there was less sorrow and more end-times certainty. She believed her children, Tylee and JJ, were zombies—hollowed-out husks hijacked by evil spirits, according to a strange doomsday theology she had recently adopted as her own. Her story wasn’t about grief; it was about control. About burning reality to the ground and building something new in its place. She didn’t spiral—she committed. Hard. And she demanded everyone else get on board or get out of her way.

And like Isla, she refused to listen. Family, friends, even her surviving son tried to reach her. Here, at least, people tried. They saw the danger. They reached out to shake her loose. They wanted to make her see reason. But by then, she’d already rewritten the script and the truth. She refused to believe her children were living, breathing people who needed their mother. Her version of reality was easier to manage than facing what she had chosen to give up.

That’s the throughline: a woman so deep in pain or delusion, she stops recognizing the people standing right in front of her.

And her family? They adapt to survive. They shut up, back off, and give up after trying countless times, because exhaustion and hopelessness take hold. But who can blame them for abandoning hope? How hard can you beg a person to see through what they’ve been so blinded by?

It’s a classic Catch-22. Keep pushing, keep calling it out, keep begging someone to see what’s right in front of them, and you risk losing them completely. But if you stop? If you let them live the lie? You risk losing everything anyway—to delusion, to the story they’ve chosen to believe, to their desperate need for something to fill the void.

In The Unseen, Isla’s family walks on eggshells for her. She’s already unraveled once. She’s dry kindling, and nobody wants to be the match that lights the next fire. Her obsession with the baby she lost—and with Rowan as the baby’s stand-in—renders the rest of the Hansen children invisible. She essentially forgets they exist, forgets she’s their mother. And Evan? He’s not protecting her, not really. He’s afraid she’ll snap, terrified she’ll pack up and disappear with Rowan, scared she’ll leave him helpless and alone, raising a family by himself. So, he goes quiet. He adapts. And in doing so, he doesn’t just lose Isla, he dooms his family to suffer her twisted reality where nothing is what it was, and no one is allowed to say so.

Grief rewires people. It makes them soft in some places, sharp in others. Sometimes you patch a hole with something terrible and call it healing, but it rips open a new wound somewhere else. Sometimes you feed the wrong thing because it’s the only thing that makes the pain shut up for a while. And sometimes you don’t even realize what you’ve let in until it’s too late.

The Unseen is a horror novel. But the scariest part isn’t what’s hiding in the trees—it’s what’s hiding in the house. It’s what happens when you know something’s wrong and you’re too scared or too tired to name it. It’s the moment when the thing sitting across from you at the dinner table—empty-eyed and grinning—isn’t half as terrifying as the person who invited it in.

___________________________________