“Tell me a story.”

It’s maybe the most uniquely human phrase. Other animals communicate (often with much greater efficiency than we do) and other animals even pass on learned techniques, travel routes, warning signals, and what could be considered a kind of culture.

But no other creature has ever said, “Tell me a story.”

What creates this need for stories to be told and heard, passed from person to person? Maybe it has something to do with the fact that we’re also the only animals who comprehend our own mortality. And so we’re the only animals who know that while our bodies will die, decay, and disappear, our stories can live on. Maybe for years. Maybe generations. Maybe even longer.

Here’s a little of my own story: I moved around a lot (thirteen different schools before high school) which meant I was always meeting new people. Unfortunately for me I was (and still am) a pathologically awkward person with no aptitude for small talk. Fortunately for me, I was born and raised in the Appalachian region among story-loving people who always had a yarn to spin. The culture in those mountains is steeped in stories: heirloom ballads about love and murder, jack tales with clever protagonists devising surprising solutions to deadly problems, and blood-curdling legends ripped straight from The Old Testament.

When I was a kid—in a world before widespread, high-speed internet, before 24-7 streaming everything on demand, before linguistic homogenization and cultural flattening—there was time to kill, hours to devour, whole evenings to do nothing but listen. And so, at every kitchen table, on every front porch, in the backseat of every car, when folks ran out of popular stories—the ones everyone knew—you’d get the good stuff. The personal stuff. The legends of self…

“No, these tattoos ain’t from the Army. They’re from when I was in prison. See, they take a tape player and a regular ol’ ink pen and…”

“We were too tired to keep going so my folks pulled over on the side of the road. My sisters and I were asleep in the backseat and, when I woke up, I saw two faces staring through the window at us…”

“…Wouldn’t you know, it was three weeks before I realized the baby she was pushing around in that stroller was a doll!”

“That right there is the hill where Bessie’s ghost still roams, looking for her son. You can see the spot where she was struck by lightning. The earth is still scarred black, even after all these years…”

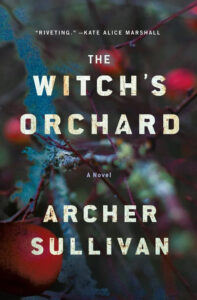

In my debut novel, The Witch’s Orchard, Private Investigator Annie Gore travels to the small, Western North Carolina town of Quartz Creek in search of two little girls who were kidnapped a decade before. She’s met with hostility, reticence, and a peculiar legend: Long ago, a witch who lived in an enchanted apple grove turned her daughters into songbirds and put them in a cage to keep them close. When they escaped, she flew after them in the form of a crow but, unable to keep up, the witch ultimately herself gave over to grief and taught the other crows of Quartz Creek her own desperate mourning song. Annie hears this story early in the book and then again and again from different townsfolk. The basic plot stays the same but, from one teller to another, the details change.

I’ve been asked about this choice. Why did I include a story at all? And why does it change?

The simple answer is that it’s a reflection of my own experience. Because I moved around so much, my childhood was a revolving door of new places, new people, and new stories. Every chance I got (knowing that I was probably going to be gone soon anyway) I took the opportunity to be as nosy as possible, asking every question I could think of and then eagerly listening to every story anyone would tell me. That open-eared, open-minded listening helped me understand something vital about stories: However far-fetched they may be, they often carry a latent, meaningful truth.

This is another part of my story:

When I was young, my aunt drove me out into the country, pulled off to the side of the road, and pointed across a barbed wire fence and an overgrown field to a high hill. She told me this was where my great grandmother, Bessie, was struck by lightning and died. After which, my grandfather—only fourteen at the time—ran away from home.

Years later, when I happened to return to that same area as a teenager, I was driving around with a friend when she pulled off to the same side of the road, pointed across the same fence and field to that same hill and told me the story of a young mother named Bessie. She said that Bessie was struck by lightning, died on the spot, and has haunted that hill ever since, looking for her missing son.

“If you look close, you can even see the black scorch mark at the top of the hill,” my friend said. “That’s where she died and that’s where her ghost emerges every night. If you stand there under a full moon, you can still hear her weeping.”

My own great grandmother, I realized, was a local legend. Decades after her death, Bessie’s story traveled from person to person on that roadside, always conveying some important lesson about love, death, and the lasting power of a mother’s grief.

This experience and others like it taught me something vital: stories are important. They matter.

From old tales of haints and devils to what happened in church last Sunday, the stories we choose to share say something about our brief experience on earth, conveying the things we don’t want lost to time. They’re proof of our existence. They tell someone—anyone who will listen—that we were here. This was our experience. This is what we feared and loved and dreamed. This is who we were.

In The Witch’s Orchard Annie confronts one version of the witch’s story and then another and another, each story changing slightly with the teller, each conveying something vital about the town, the history, the shared fears and shrouded scars. And, over the course of the novel, Annie learns the same thing I did: important truths often hide under layers of legend. It’s only by peeling away those layers that we can finally shed light on that hidden truth.

Of course sometimes the truth is hidden for a reason. Sometimes, as Annie will discover, it’s a truth worth killing for.

***