The day after Thanksgiving, 1977, I arrived at the Statler Hilton (today it’s the Hotel Pennsylvania) early in the morning for the Creation Comic Book Convention. When the doors opened at 11 am, I walked through the crowd and slowly absorbed the spectacle surrounding me. Part of the allure of attending any convention, besides buying back issues and related merchandise (fanzines, undergrounds, original art) was meeting the comic book artists. On the left of one of a medium sized ballroom was what has become known as Artist’s Alley, a section where the pencillers and inkers gathered behind tables and drew sketches for five to ten dollars. Many of the attendees, myself included, brought along sketch books with the sole purpose of collecting as many drawings as possible.

During that period, comic book artists were the lowest paid professionals in the field and convention sketches became a lucrative side hustle. However, beginning in the mid-70s, many young talents, tired of being disrespected, began expanding their horizons by dabbling in paperback covers, animation, magazine illustrations, movie posters, and advertising storyboards as well as the then-new market of high quality portfolios, posters, art books and limited-edition prints. Boutique publishers that included Supergraphics, Christopher Enterprises, StarReach, Eclipse, Byron Preiss Visual Publications, Sal Q. Productions and Schanes & Schanes were also on the horizon. Artists Howard Chaykin, Alex Nino, Neal Adams, Frank Brunner, Jim Starlin, Mike Ploog and others were part of that new vanguard.

At the Creation Con, most of the artists wore name tags and were in jovial moods as they talked to one another and the fans. That first day I saw Marshall Rogers, who would soon become my favorite Batman artist, sitting on top of a table drawing the Caped Crusader. Across the room fans gathered around Avengers/ Conan artist John Buscema while white haired Daredevil penciler Gene Colan sat next to relative newcomer George Perez who was signing copies of Logan’s Run. Art students Tom Yates, Steve Bissette and John Totleben, who all studied at the Joe Kubert School, shared a table and talked amongst themselves. Meanwhile, in the rear of the room, emerging fantasy artists Marcus Boas, Robert (Bob) Gould and Charles Vess, who years later illustrated several projects including Stardust with writer Neil Gaiman.

After striking up a conversation with Vess, I learned he had just moved to New York City the year before and was contributing fantasy art to small fanzines, though he’d soon be published in Heavy Metal, which had just begun publishing that year. A 26-year-old southern gent from Virginia, he and I talked for a while as I flipped through his portfolio of drawings. I told Vess how much I liked his work, and mentioned that his style and subject matter reminded me of my favorite comic artists Berni Wrightson and Michael Wm. Kaluta. Both were known for their outstanding horror work as well as career defining books Swamp Thing and The Shadow.

“Well, thank you,” he replied. “I’m very much inspired by those guys. In fact, Michael Kaluta and I share an apartment. He’s here, at the convention, showing his work in the room across the hall.” After thanking Vess, I quickly gathered my belongings and dashed into the crowded hallway. There were a few rooms to consider, but I finally located the correct one.

Stepping inside, that room was the equivalent of discovering a new world, one that stirred my creative juices as well my perspective on so-called comic book art. While it was true that Kaluta’s work was displayed, it wasn’t the usual comic pages, but instead there were massive paintings hung throughout the room as well as prints and small press books. Kaluta was sharing the room with Wrightson, Barry Windsor-Smith and Jeff Jones, an artist I wasn’t familiar with before that day. Jones, I soon learned, had done a few comic book stories, but was best known for his science fiction/fantasy paperback covers.

Wrightson, Kaluta and Jones all started out painting in the style of Frank Frazetta, the genre illustrator who was the art messiah that they all emulated early in their careers. The three upstarts met at a convention in 1967, where they went to meet Frazetta. The following year, Windsor-Smith became a Marvel Comics artist known for his work on Conan the Barbarian. A Brit-expat, Smith’s early work was reminiscent of Jack Kirby, but he quickly developed into one of the best in the business.

Before bowing out of the comics industry to devote himself to painting and publishing prints through the self-owned Gorblimey Press, Smith contributed the award-winning The Song of Red Sonja and Red Nails in 1973, stories that demonstrated the daring direction his art was moving towards. Two years later, Smith, Wrightson, Kaluta and Jones, rented a huge loft on the 12th floor of an industrial building 37 West 26th Street where they produced work that reshaped their careers. Collectively paying $400 a month for the former machine shop space in Chelsea, there were high ceilings, creaky floors and rodents.

The scope, scale and vision of their new work was the visual equivalent of Bob Dylan going electric…

At night, when the artists were still painting, the building’s heat was turned off, and it could get very cold, but that didn’t stop them from putting in the work. Having stepped away, at least momentarily, from the traditional comic book medium, the scope, scale and vision of their new work was the visual equivalent of Bob Dylan going electric, walking the line between commercial and fine art. At the convention, on display were Wrightson’s creepy paintings from his Edgar A. Poe portfolio, the magical beauty of Smith’s brilliant Pre-Raphaelite styled canvases Fate Sowing the Stars and The Devil’s Lake, and the whimsical romanticism of Michael Wm. Kaluta’s stunning The Sentry and The Sacrifice.

With the exception of Windsor-Smith, who sat with a scowl on his face most of the weekend, the artists were approachable and cool. However, it was the work of Jeff Jones that affected me the most. His paintings The Wall, Blind Narcissus (the piece was so large, it had to be lowered from his studio window by rope) and the hand-colored print In a Sheltered Corner were beautifully haunting images. Jones’ pictures of women, alone in their own worlds, were blissful, gentle and alluring images that pulled me into their landscapes of isolation.

Whereas most fantasy artists of that era drew in a macho style, Jones painted with sensitive strokes. His work was visual Emo, the dreamy visual equivalent of Pink Floyd and Kate Bush. “Jeff’s paintings had something else,” former protégé George Pratt wrote in a 2019 essay. “Hard to describe. Hard to nail down. But they lived in a different space that was emotionally deeper, for me at least. They were rich in self-reflection, a mood at once quieter, contemplative, and more viscerally honest.”

Decades after seeing Jones’ work at the Creation Con, I thought about my first experience with his work while watching Maria Paz Cabardo’s 2012 documentary on the artist Better Things: The Life and Choices of Jeffrey Catherine Jones, currently streaming on Kanopy. The fantastic film covers Jones’ life from his art loving southern boy roots in Atlanta, Georgia, raised by a beautiful mother and a stern, former military daddy who believed that “artists are bums” to his (her) last years living as a transwoman after beginning hormone replacement therapy in 1998 at the age of 55 and renaming herself Catherine.

Still, Jones had no problem be referred as Jeff when discussing earlier work. “Catherine did not paint the paintings or draw the drawings,” Jones told friend and The Art of Jeffrey Jones co-editor Arnie Fenner in 2006. “Jeff Jones did; they’re the result of his efforts. Jeffrey Jones. That’s how people know me. That’s how I want to be remembered.” Later, friends would say that Jones confessed that the hormones were a mistake, but in the film Better Things she looks comfortable and peaceful. Still, as the viewer learns, it wasn’t always that way.

In between Jones’ brilliant career full of achievements and accolades there was much mental agony that began in childhood that led to divorces, alcoholism, nervous breakdowns, conflicts with art directors, hospitalization, homelessness and, at times, a complete lack of desire to draw or paint. But, after each setback, Jones somehow managed to bounce back and continue creating.

***

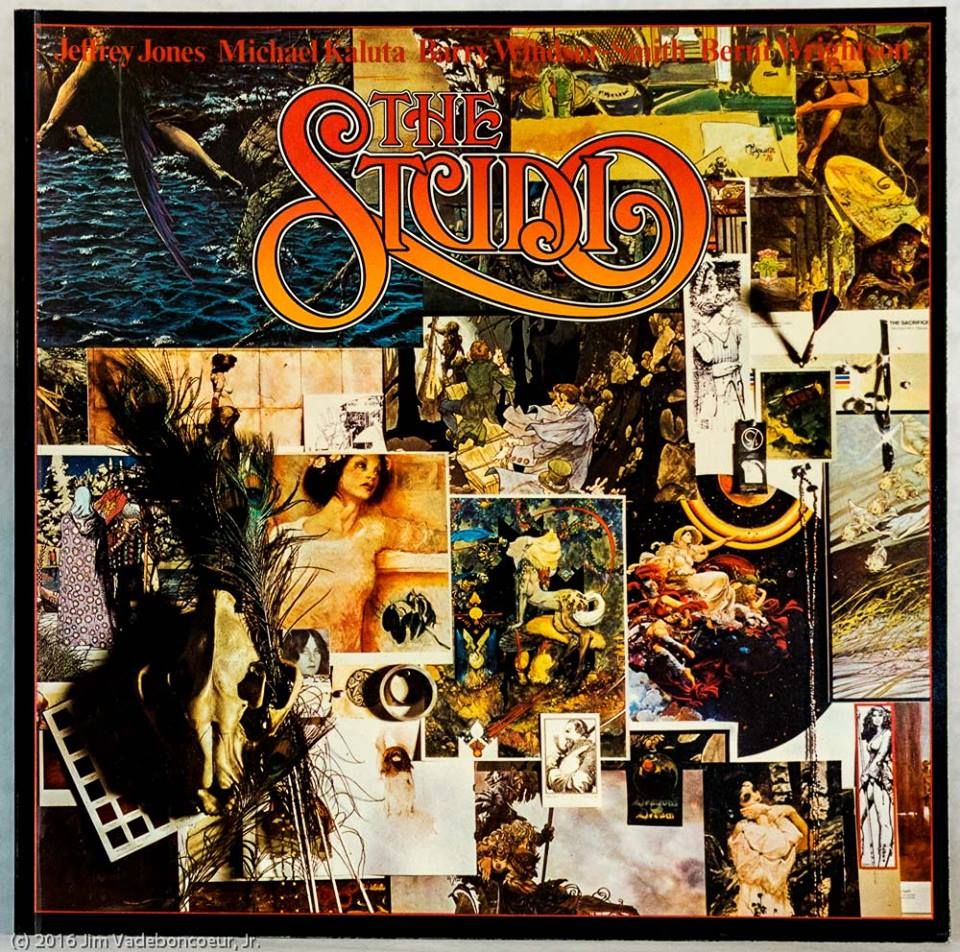

The group paintings on exhibit at that 1977 showcase was just a sampling of the work that would be published in the influential 1979 book The Studio (Dragon’s Dream), a tome cited by next generation comic art favorites Kent Williams, Rebecca Guay, Jon J. Muth, Julie Bell, Dave McKean, Ashley Wood, Paul Pope, Bill Sienkiewicz and countless other art straddlers who comfortably move between graphic novels, children’s books, advertising and fine art.

“Though the existence of The Studio was brief-it lasted from 1975 to 1979-the artistic experiments conducted by its multi-talent quartet helped redefine comic art in illustrative terms,” Chris Lawrence wrote in The Art of Painted Comics, “enabling (and encouraging) those who followed to apply those illustration techniques directly to the world of sequential storytelling.” In that same book, George Pratt, who went to Brooklyn’s renowned Pratt Institute with Williams and Muth, says, “Jeff was one of our gods…his work blew me away. He was our Rembrandt.”

Certainly, I too could understand the feeling since I quickly fell in love with Jones’ work from the moment I the work. Although I didn’t yet know the names of painters John Singer Sargent or N. C. Wyeth, as a New York City boy I’d been to the Metropolitan Museum of Art enough to equate the man behind the table was adding a new twist to the old masters. In 2004, Jones told Laurie J. Anderson at Sequential Tart that Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Johannes Vermeer and Rembrandt were three influences.

“The life, and the strength, and the way they broke from classical art,” Jones said. “The Renaissance was just a period of exploding creativity. The old Masters worked from their passion and their hearts to create extraordinary pictures. Every time I go back to them I see something new. There’s so much beneath the surface.” By the time I encountered his art, Jones had been nominated for numerous Hugo Awards and later won a World Fantasy Award.

***

That post-Thanksgiving Friday, on Jones’ convention table, there were prints of a painting called Descent, a disturbing picture of a pregnant woman wearing a gasmask, an image that struck me like a bolt of thunder. At fourteen, I had no idea the image was a homage to Gustav Klimt’s The Three Ages of Woman (1915), but I knew I’d never seen any expectant women in the paintings before. Trying to understand what I was viewing, I asked Jones what inspired him to paint it. “I think women are at their most beautiful when they’re pregnant,” he replied in a voice that was gentle, and, if I remember correctly, still retained a slight southern accent. His simple explanation stayed with me ever since.

“Leave your sketch book. You can pick it up in a few hours.”

Having stayed in that art room longer than expected, I was ready to join the hordes of fans roaming through the hotel, but I thought I’d roll the dice first. “Mr. Jones, do you think you could do a sketch for me?” He looked at me and smiled. “I don’t really do convention sketches anymore.” I was deflated, and, before I knew it was whining as though I was one of the Little Rascals. “Ahhhh, come on.” Years later I felt shame, but as a teenager I had none. “OK,” Jones agreed quickly. “Leave your sketch book. You can pick it up in a few hours.”

When I returned, Jones handed me back the pad where he had drawn the side profile of a mysterious woman gazing into the distance. The image, centered on the page and sketched in black ink, was stunning and powerfully beautiful in a quiet way. Though I offered pay him $5.00 (hey, I was a kid), he simply said, “It’s fine. I want you to have it.” Years later, I read that Jones often gave away art to people he knew appreciated it. “I enjoy it when people like my work, because I want to have added something to this world, or whatever gave me life, instead of just taking from it.”

That afternoon was the last time I saw Jones in person, though I did continue, to this day, to collect his work in the form of second-hand paperbacks, dusty sci-fi digests and various art books. Although the drawing he did for me was lost long ago, it was that giant act of generosity that stayed with me and which I try to replicate when interacting with young creatives.

***

Growing-up in Atlanta, Jones wasn’t exposed to fine art until adulthood, but like many comic book artists of coming of age in the 1950s, he was a fan of the infamous EC Comics and its roster of graphic geniuses that included Wally Wood, Al Williamson and Frank Frazetta. “I remember reading the ECs as they came out,” Jones told Jon B. Cooke in 2001. “It was only later that I realized how much my vision had been formed by them.” He was also an admirer of N.C. Wyeth. “He could tell a story in a single picture.” Jones entered Georgia State College as a physics major, but switched to art studies a year later. Concentrating in German Expressionism, it was in art class he met where future Mary Louise Alexander in 1964 and married her two years later.

Jones’ professional career began in the mid-1960s after marrying in 1966. Louise fully supported his dream to move to Manhattan to become an illustrator and comic book artist. As Jones admits in Better Things, if it wasn’t for Louise, who later became a much respected editor and writer, he might not have had the courage to come to the Big (Rotting) Apple. In the winter of 1967, Jones found them a place in the Yorkville section of the city. Unlike Jones’ native Atlanta, the streets of Manhattan were dirty and the crime rate was high, but the rents were still cheap enough for aspiring artists, writers, musicians and filmmakers to afford to live.

“Knocking on doors of supers I found an Apt. on 82nd St, $100 a month,” he wrote in 2003 in an online journal. “First floor down beneath street level–roaches, dirty, small and no ventilation.” The apartment was far from the opulence of the Atlanta house he was raised in on Ponce de Leon Avenue that was “resplendent with ivy carpeted yards, privet taller than he and clay tennis courts, dry and powdery, spreading quietly behind gardens of Victorian wildness… the grounds that spread about the house were green and lush and smelled of age and invention.”

Jeff was able to find work immediately at Creepy, a Warren Publishing horror comic magazine edited by Archie Goodwin. The sample strip “Dragon Slayer” Jones used to get in the door was scripted by Louise. Goodwin gave young Jeff a script he wrote called “Angel of Doom.” Though excited, Jones initially had a panic attack, but eventually “knocked the roaches off” of his drawing board and completed the six-page strip.

Jones’ early work was crude, but promising. He soon got more assignments from Goodwin, but the artist was also submitting to various fanzines and smaller companies that included Gold Key and Charlton, where, like his hero Alex Raymond, he drew Flash Gordon. During that period Jones became a father when daughter Julianna was born in 1967. “It was the greatest thing that ever happened to me,” Jones said. That same year, Jones painted his first publication cover when Donald M. Grant commissioned him to illustrate the Robert E. Howard/Solomon Kane book Red Shadows. Published in 1968, that cover put him on the radar of art directors looking for the next Frank Frazetta.

But things soon took a turn when his wife discovered his secret life. In the doc, Louise refuses to disclose how she discovered Jeff’s secret, but it caused a major shift in the couple’s relationship.

“I knew I was born to the wrong body since I was five years old,” Jones said in Better Things. Meanwhile, in his online journal, Jones noted. “In the south, in the ’50s there were no gays and no lesbians, and certainly no one like me. So I became secretive.” In 1973 Last Gasp reprinted Jones’ more underground strips in the collection Spasm, which showed how fast his style was developing towards what artist Pete Doree described as “feather light visual poetry.” Jones’ pen & ink technique was progressing towards a more minimally expressionistic style that would bloom full as Van Gogh’s sunflowers in the wonderfully surreal one-page comic Idyl. Created and drawn for National Lampoon from 1972 to 1975, in most of the stories an attractive pregnant woman wandered a desolate, apocalyptic landscape musing philosophically with talking fishing floating through the air, reptiles and animals.

In a blurb on the 2015 Donald M. Grant edition, writer Neil Gaiman compared Idyl to “modern poetry” while they reminded me of a Jean-Luc Godard shorts starring Anna Karina. “Idyl was intended as satire and whimsy,” Jones said in 2001. “One art director and one editor, who met me each month with puzzled faces, continued to remind me that National Lampoon was a humor magazine, ‘As long as YOU laugh,’ they finally said. So each month I would go in laughing. I also must admit that I love to draw nude women.”

Still, unlike his future Studio mates, Jones moved away from mainstream comics early and began to specialize more in science fiction/fantasy magazine/book covers and interiors. “It was an easy time to break in,” Jones said in Better Things. He was prolific and produced beautiful covers for the Ted White edited Amazing and Fantastic as well as stand-out paperbacks that included The Jewels of Aptor by Samuel R. Delany, The Sowers of the Thunder by Robert E. Howard and The Doors of His Face, The Lamps of His Mouth, and Other Stories by Roger Zelazny. In addition he also illustrated numerous novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ popular Tarzan and Fritz Leiber’s sword swinging duo Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser

After Louise left him, Jones formed a bond with fellow “cross-dressing,” as he described himself, artist Vaughn Bodē when the two met at convention. A brilliant, whimsical artist whose wacky characters Deadbone and Cheech Wizard has inspired legions of graffiti artists, animator Ralph Bakshi, cartoonist Dave Sim and his own talented son Mark, the senior Bodē felt a kinship to Jones. At that point, Jones dressed in women’s clothes when he was at home only, but was encouraged by Bodē’s femme-openness. “Vaughn’s courage in going public inspired Jones, and Jones’s admiration emboldened Vaughn,” journalist Bob Levin wrote in his 2005 The Comics Journal essay “I See My Light Come Shining,” an impressive piece on the life of Bodē.

They worked together, played together and inspired one another. According to Levin’s article, both men experimented with hormones, but stopped.

From June 1, 1972 to April 1973 they shared a “40-year-old stone-and-wood English country house three miles outside Woodstock.” They worked together, played together and inspired one another. According to Levin’s article, both men experimented with hormones, but stopped. They were also into bondage, which would explain Jones’ S&M inspired Wonder Woman covers in 1972. A year later, when the lease was up, Bodē moved to San Francisco to be closer to the underground comix scene, reuniting with friends Spain Rodriguez and Trina Robbins, while Jones headed back rhythm and chaos of the city.

As we learn in Better Things, their friendship took a few interesting twists that included Jones sleeping with his friend’s woman Diane Pitre Stevens; it all ended tragically in 1975 when Bode accidently killed himself during erotic asphyxiation. That same year Jones joined forces with The Studio, but he was forever haunted by his friend’s sudden death. The four years Jones spent at The Studio was intense, but productive. According to Kaluta, he and Jones spent the most time there, going home only to get their mail.

At the end of the 70s, just as The Studio book was setting free the ambition and imagination of creative darlings across the globe, the artists disband. Eventually Smith, Wrightson and Kaluta returned to comics, but Jones, with the exception of the Heavy Metal one-page strip “I’m Age” that ran from September 1981 to July 1984, turned his back on the medium as well as commercial illustration and called it “immoral.” Jones lived on selling older pieces and accepting private commissions while also licensing his work to art books (1994s Age of Innocence: The Romantic Art of Jeffrey Jones is a personal favorite), jigsaw puzzles and fantasy art trading cards.

In his personal life, though Jones continued to have relationships with women, there was a serious internal struggle with his own sexuality. “He had felt conflicted about his gender since childhood, always feeling a greater affinity for the fair sex than for his own maleness,” Steven Ringgenberg wrote in his wonderful 2011 essay A Life Lived Deeply. “Having grown up as a product of the patriarchal 1950s, with a domineering war-hero father, Jones did not know how to cope with his yearning to be female, and felt ashamed. For years he tried to drown these feelings in alcohol, but, after much soul-searching, Jones realized that although he’d been born male, inside he was a woman. He began hormone replacement therapy in 1998, and set out upon a new phase of life as a woman, changing his name to Jeffrey Catherine Jones.”

Over the next 13 years of her life, Jones went through various troubles that included a nervous breakdown, homelessness and depression. Towards the end, she suffered emphysema and bronchitis. In her last days, Jones was living in Kingston, New York, where she liked painting landscapes in the Catskills. Jeffery Catherine died on May 19, 2011 at the age of 67. According to The Comics Reporter writer Tom Spurgeon, “It was asserted that the doctor noted some hardening of the arteries around the heart as well. She was too weak and severely underweight to muster a fight, and had in fact been brought into hospice care early this week after a period of rapid decline. There was no resuscitation order.”

Though I’d only met Jones that one time in 1977, I had been very much inspired by the numerous comic pages, sketches and paintings I’d seen over the years and her passing hit me hard. Better Things, which wasn’t completed until after Jones’ death, tells a much more sorrowful tale than I’d anticipated, but also serves as a celebration of Jones’ life and genius. As French graphic artist Mœbius said towards the end of the documentary, “If you fly, you are falling all the time.” In the case of artist Jeffrey Catherine Jones, nobody ever flew higher.