It is fair to say true crime is having more than a “moment.”

According to a recent YouGov poll, a third of Americans consume true crime at least once a week with shows on Netflix regularly trending in its top ten. While on TikTok, the hashtag #truecrime has nearly 20 billion views. True crime is not simply the largest subcategory of documentaries, it is also growing at a faster rate than all other genres.

With the explosion of public interest and the emergence of true crime into the mainstream, what are the responsibilities of authors and program makers when fictionalizing or dramatizing real-life cases?

How do we ensure we do not become titillating in our re-telling? How do we interrogate the perpetrator’s drivers and background without shifting the light away from the victims? How do we guard against being exploitative or insensitive to those left behind?

And how do we give killers a human face without glorifying them? Or worse perhaps, depict a handsome and charming murderer like Bundy without falling into the trap of over sexualizing him?

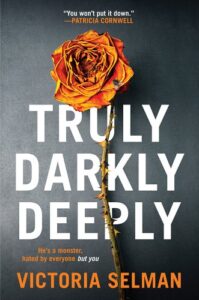

My latest novel, Truly, Darkly, Deeply—which was very much inspired by true crime and was an instant Sunday Times bestseller in the UK (possibly again demonstrating the appeal of the genre)—investigates the relationship between a charismatic serial killer and a young girl who was integral to his conviction who, twenty years after his incarceration, still can’t be sure whether he’s actually guilty.

Truly, Darkly, Deeply is a dual timeline narrative. We see child Sophie interacting with her mother’s boyfriend, Matty Melgren, in the buildup to the string of murders he will ultimately be convicted for. And we see grown-up Sophie grappling with the questions that have haunted her whole adult life: Is Melgren really a killer? Were the clues there all along? Or is hindsight superimposing warnings were before there were none?

A serial killer’s legacy explored through the eyes of a child in his life draws on a number of real-life cases—such as “BTK” Dennis Rader, the “Green River Killer” Gary Ridgway, and Ted Bundy—who all maintained apparently regular family lives yet managed to conceal their “activities” from their wives and children. In other words, men who managed to hide their proclivities behind a mask of normalcy.

The book taps into my fascination with the criminal psyche. What intrigues me just as much as the mentality of evil is how serialists are able to dupe those close to them, that it is possible to share your life with one without ever suspecting it.

Much has been written from the perspective of the serial killer’s wife, but it struck me that very little has been penned from the viewpoint of a child. I wanted to understand that relationship and its legacy without in any way celebrating “the killer” while also as looking at what it means to be a monster—and to love one.

This meant portraying the human side of a serial killer, which of course presents something of an ethical dilemma. After all, is presenting a serialist as “not all bad” a step toward empathizing and therefore forgiving him?

I don’t think so! Portraying a killer as multifaceted is about painting a realistic picture. No one is purely good or evil. Everyone is the hero of their own story and only Disney villains go around twirling their mustaches and saying “Mwah ha ha . . .”

And isn’t a killer who is kind to a child and has a penchant for Baskin Robbins ice cream and a silly sense of humor, more rather than less disturbing than a cartoon character we can’t relate to?

It is comforting to believe evil has a face, that we would recognize it if we stumbled into its path. But the women who flocked to the courthouse every day to watch Ted Bundy’s trial and told reporters they didn’t think he was guilty because he didn’t “look like a killer” show that the worst people are often the ones who appear most human. Bundy certainly appeared that way—a man who murdered 30 people across the United States but was able to blend in so well, no-one ever suspected him.

If the best crime fiction doesn’t just entertain but also holds a candle up to society, is it not important to portray crimes and killers as realistically as possible?

Filmmakers have been criticized for sexualizing Bundy via the movie, Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, in which Hollywood pretty boy Zac Efron was given the role of Bundy. The argument is that casting a heartthrob as an infamous killer undermines our instinct to condemn him.

It is seen as an affront to his victims. A disservice. But I believe that NOT portraying him as good-looking and charming would be the true disservice to the reality of who Bundy was and how he was able to fool those closest to him.

Jeffrey Dahmer is yet another example of a killer that television makers have been lambasted for portraying as handsome. In the Netflix show, Dahmer–Monster, we see actor Evan Peters doing weights and revealing his rather muscular abdomen glistening with sweat.

Is that wrong? After all, both Bundy and Dahmer used their looks to draw in their targets—as does my character, Matty Melgren.

Adult Sophie talks about the issue of sexualizing a killer. Like Bundy, there is a movie made about Melgren where the producers get stick for casting such a handsome actor. But Sophie wonders, wouldn’t playing down his attractiveness be an insult to the women he killed? After all, if Matty had a socially awkward “troll,” he would not have been able to lure his prey the way he did and get them to trust him.

Leaving that aspect out of any narrative wouldn’t only be inaccurate; it would also fail to explain why their victims were taken in by them. And indeed, in a society so preoccupied with physicality—why in similar circumstances, any of us might have been too.

In Truly, Darkly, Deeply, I have drawn a perpetrator who is handsome and charming. I am not trying to glorify “the killer,” but rather I am aiming to show the ripple effects of his crimes and why he was able to dupe both his victims and those close to him.

In doing so, I hope I have created a novel that explores the impact of serial killers on those left behind, the reality of how they were able to do what they did—without in any way celebrating the monster.

***