“It feels, indeed, as if the characters and everything that happens to them exist in some limbo of the imagination, so that what I am doing is not inventing them but getting in touch with them and putting their story down in black and white, a process of revelation, not of creation.”

Nobody could put it better than that. The quotation comes from the inimitable P. D. James, in Talking About Detective Fiction.

And that’s what it’s like for me: the characters are there, somewhere in that limbo, and I check in with them whenever I want to see what they’re up to. So, character is, to me, the most important element of a story. And I must have succeeded to some extent: I get very strong reactions to my three main characters: Monty Collins, Father Brennan Burke, and Maura MacNeil. With respect to Monty, I attended a book club one time, and one reader referred to Monty; she said quite heatedly that she would never advise her children to go to a lawyer like Monty! I said, “You would if you wanted them acquitted of murder.” Some people find Maura MacNeil a little too lippy; she does have a mouth on her, no question. Brennan Burke once said, “She has a tongue in her head that could slit the hull of a freighter.”

Father Burke inspires the strongest and most frequent reactions. I’ve had everything from love — “What church is he at? I’m a single woman and I’d like to meet him.” — to outrage about his boozing and his (only occasionally) breaking of his vows, in particular, the promise to live a life of chastity. One reader declared: “He is not fit to do anything but get down on his knees and scrub the floor of his church!” I’ve even had readers worry about him: “What’s he going to do about this?” Or, “You can’t let that happen to Brennan!” This tells me that I have created (or, citing P.D. James, I am in touch with) a character who is not bland or forgettable; my readers are not indifferent to him.

In order to portray a believable and compelling character, a writer has to have an ear for dialogue. I love writing dialogue, and regional dialects. If I sit at a table with a group of people, I may not be able to remember afterwards what anybody was wearing. But I can recall conversations, often word for word, and I can bring back the accents, the tone and cadence of the voices. I find in some writers’ books that the dialogue doesn’t ring true and the attempts at humour fall flat. It’s not all that easy to do, or not easy to do well. An intelligent, witty character should sound it; an old lag doing hard time in a cell should talk like one.

Inseparable from all this is the “voice”, the voice in which the story is told, whether it’s a character speaking in the first person, or the voice of the author/narrator. Sometimes the voice alone, if the writing is particularly fine, is enough to hook me on a story or a series. It could be the wit of Caroline Graham in her Midsomer Murders series, the unapologetic erudition of Dorothy L. Sayers in the Lord Peter Wimsey books, or the evocative, poetic writing of R.J. Ellory in A Quiet Belief in Angels. Or John Brady, rightly commended in this New York Times review of his Matt Minogue series:

“Although he writes with realistic precision of Irish police procedures, Mr. Brady adopts a tone of battered lyricism for Minogue’s keening thoughts about the spiritual corruption he sees around him. It’s a sad sound, the lamentations of a decent man’s conscience, but it’s the music that keeps drawing us back to this haunting series.”

How many writers could ever hope to reach that pinnacle of achievement?!

Having said all that, it’s interesting to recall the importance that P.D. James accorded to setting.

“Place, after all, is where the characters play out their tragicomedies, and it is only if the action is firmly rooted in a physical reality that we can enter fully into their world.”

Of course, she portrays setting brilliantly in her novels.

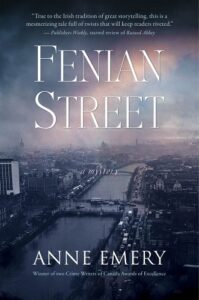

Setting is important to me, as well. Not surprisingly, my stories are set in places that hold great interest for me, e.g., my own city of Halifax, Nova Scotia; Dublin and other cities in Ireland; Italy; and Germany. My most recent novel, Fenian Street, was inspired directly by the street of that name in Dublin. Historically, and at the time of my novel — the 1970s — it was a street of tenements, called the Corpo Flats there, meaning public housing for the poor and working classes. My main character, Shay Rynne, is a lad from the Corpo Flats in Fenian Street, who wants to succeed in the Garda Síochána, the Irish police, despite the prejudice against him because of his background.

Now, here are a few of my most cherished writers, who excel in the elements of setting and character.

With such an illustrious history of writing and storytelling, Ireland has so many great writers that a list would fill volumes. I’ll mention only a few of my favourites. Liz Nugent is exceptional at creating character and suspense, from Unraveling Oliver through to Little Cruelties. For a brilliantly written police series set in Dublin, see Tana French’s Dublin Murder Squad series, beginning with In the Woods. A recent standalone novel is The Searcher.

And we have Adrian McKinty’s Sean Duffy series. The books are set in McKinty’s native town, Carrickfergus, and the surrounding areas, including Belfast. McKinty transports you right into the turmoil of Northern Ireland. There are six books in the Duffy series, with the seventh expected soon: The Detective Up Late. Another great crime writer from the North of Ireland is Stuart Neville. He was born in Armagh and, like McKinty, knows all about the dark side of life in his native land. He has an excellent series of crime novels starting with The Ghosts of Belfast (a.k.a. The Twelve) and, most recently, a standalone novel, The House of Ashes. Ironically, Neville has revealed, when he first started writing about his home country and seeking to publish his work, he was told that setting stories in Northern Ireland was “death for sales” and he should try to disguise or play down the setting in promotional materials! His first novel had to be titled The Twelve for sales in the U.K. instead of The Ghosts of Belfast. Neville and McKinty have certainly overcome that particular prejudice. And, interestingly, the two of them are the editors of a collection titled Belfast Noir.

Moving on to Italy. Donna Leon writes a wonderful series set in Venice, featuring Commissario Guido Brunetti. Brunetti is a wonderfully drawn character, one I keep coming back to. And the secretary in the Questura, Signorina Elettra, is one of a kind; she is a genius at doing things for Brunetti on the sly, mining her computer and digging up any information Brunetti needs, often information that is meant to be inaccessible. Leon, via Brunetti, has an uncanny ability to penetrate people’s minds, revealing with wit and asperity aspects of the characters’ behavior and thoughts that the characters do not know they are revealing. And her descriptions of Venice make you feel you are right in the centre of that legendary city. The most recent book, number 31(!) in the series, is Give Unto Others.

Finally, we turn to Germany, and one of the greatest-ever writers of historical fiction, Robert Harris. He has set stories in ancient Rome, England, France, and Russia among other places. I particularly like his books about Germany, namely Fatherland, Munich and V2. His recreation of places and past times is incomparable. He has a new book out, Act of Oblivion, about the 1649 murder of King Charles I.

And now I’ll return to my own city, Halifax, which suffered catastrophic damage in the explosion of December 6, 1917, an event which has inspired many writers of fiction and non-fiction, and I intend to be one of them.

***