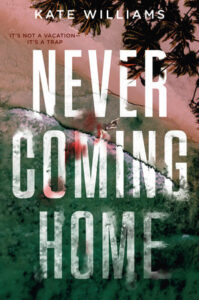

When I set out to write my young adult novel Never Coming Home, my number one goal was to create a killer mystery. My number two was to write a cast of characters that the reader just couldn’t wait to see die. Never Coming Home is a contemporary, social media-based retelling of Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None, the story of 10 strangers who are all invited to a mysterious island under sketchy circumstances. Once they arrive, it isn’t too long before they’re hit with the big M: murder.

While Queen Christie’s masterful storytelling and deft deployment of the red herring definitely drew me to the idea of reimagining this story, what really hooked me was that many of the characters in it were deliciously awful. Take beautiful, dumb Anthony Marston, whose selfishness is so pure that it’s almost to be admired. Almost. Or Emily Brent, a pious, self-righteous spinster who regularly indulges in the deadliest sin (pride, that is). Philip Lombard is the closest the book has to a hero, and he’s as morally gray as they come (though any quick scroll through #booktok will inform you that a morally gray hero is actually what the boys and girls want these days).

From the very beginning, it seemed obvious to me that my characters would all be social media influencers. For the young adult audience, who engages with YouTube and TikTok more than they do any form of traditional media, influencers are “it.” However, this demographic is not content just being influenced—they also want to influence. A 2019 study conducted by marketing research firm Morning Consult found that 86 percent of people ages 13 to 38 reported that they wanted to become a social media influencer, while 12 percent reported that they already were. Fame and fortune are part of the lure of becoming a social media influencer, but I think what really makes it so enticing is that it seems so accessible. Social media has made it possible for anyone, anywhere, to hit it big right from their bedroom, and a viral post can change a life instantaneously. You can wake up a nobody and go to bed a star, so no wonder this kind of fame seems particularly sparkly.

However, influencers are embroiled in scandal just as often as traditional celebrities. If not more, even, since many lack the PR and management machines that often oversee the careers of young actors or musicians. There’s James Charles’ racist tweets and constant feuds; TikTokers Sway House flouting quarantine to throw parties; Josh Richards exposing himself during an Instagram Live; the D’Amelio sisters perceived mistreatment of a private chef; Ava Majury’s father killing her stalker; breakups, cheating, backstabbing friendships, and even a throuple of Bella Thorne, Tana Mongeau and Mod Sun (if you don’t know who any of these people are, that is totally ok! It just means you’re over 25!). So, while youth culture has a passionate relationship with influencers, it’s also a complicated one. What could be more fertile ground for a murder mystery?

In Never Coming Home, much like And Then There Were None, ten strangers are invited to an island. This time, the island is a much-hyped luxury resort on a private tropical island, and the strangers are all bright young things with big followings. There’s a TikTok superstar, a gamer, a CEO, and a beauty blogger, among other identifiable types. I chose each type deliberately to inspire both admiration and eye-rolling. For example, beauty bloggers make big bucks with sponsorships, get tons of freebies, and seem to just travel the world taking pictures of themselves looking hot. Must be nice. But from the hater POV, isn’t that kind of silly? I mean, there are so many real problems out there, so does the world really need another beach waves tutorial? But also, how did you do it and can I do it too?

When I started writing, tropes such as this were at the forefront of my mind, because I wanted to create characters that people would love to hate. My cast would be diverse but have the shared traits of selfishness and hunger for fame, their unlikability easily identifiable to everyone but themselves. My type-A chef’s perfectionism would be ridiculous. My junior politician can’t work a room nearly as well as he thought he could, and my rich girl would be as bored (and boring) on the beach as she was in Bel-Air. My initial idea was to make these characters viscerally unappealing so that the reader would keep turning the page, waiting, hoping, for them to get what was coming to them.

Before I start writing a book, I do a detailed outline, fully knowing that the story will evolve and grow once I get into the groove. For me, the unexpected twists and turns my books take is the most fun part of writing, but when writing Never Coming Home, the strangest thing happened. My story stayed very close to my original outline, and it was my teenage characters who evolved. They got backstories, and then those backstories became more complicated. They didn’t just want to be famous because they were superficial. Instead, they sought fame as an escape, a second chance, or as the precious validation they weren’t getting from anywhere else. As the story wove on, they confessed their wrongs and took accountability. They committed unselfish acts, and tried to save each other’s lives, coming to terms with their pasts and reckoning with their (lack of) futures. They were all flawed and complex and while many never truly became likable, they became something even better: real.

In the 2018 documentary The Orange Years: The Nickelodeon Story, executives talked about how much of the channel’s early programming was guided by the belief that “all kids feel stupid and alone on the inside.” This is inherently true—I spent much of my own tween and teen years despairing that nobody liked me. I remember one mortifying incident after a Scholastic Book Fair when our book orders arrived and the teacher read aloud the titles we’d bought as she handed them out. I’d purchased a book called “How to Make Friends,” and when she dropped it on my desk, I tried to pretend it was a mistake (classmates fooled: zero).

A lot of content geared toward kids and young adults, however, is still packed with characters who are pretty and popular, who save the day rather than wreck it, and who are victims of others misdeeds rather than perpetrators of their own. While these characters may be fun to read, they’re hard to identify with. They drive home the erroneous idea that everyone except YOU, dear reader, is perfect, so when it comes to ugly emotions, glaring screw-ups and messy lives, you’re on your own.

When you have unlikable characters, especially unlikable female characters, who grow and evolve without ever achieving the gloss of perfection, you will inevitably turn off some readers. But in others, you will inspire a connection. These readers will cheer for your characters’ triumphs and mourn their failings. They will want your characters to get better and do better, but they will not expect them to become completely different people. And as your readers cultivate empathy for these people on the page, they will hopefully do the same for themselves. When readers fall for an imperfect person on the page, ideas are planted, very deep and unnoticed at first, but those ideas grow and spread and permeate and soon turn into beliefs that transcend fiction and take root in the real world: Flaws are not fatal, life is complicated, and being likable is not a requirement for love.

***