If your last name was Farto, would you want people nicknaming you Bum? Evidently Joseph “Bum” Farto didn’t mind it a bit, and that alone probably hints at his being a person of interest.

Born in 1919 across the street from the Key West Fire Department, Bum Farto hired on as a fireman in the 1940s and worked his way through the ranks until becoming the fire chief in 1964. Fate handed him that job thanks to a long tenure and an FBI investigation into corruption in both the island’s fire and police departments, the result of which entailed the resignation of then Fire Chief Charles Cremata and Police Chief George Gomez. Combined with a new police chief, Farto gave rise to hopes by the island’s residents that he would clean things up and restore order in the all-important fire department—most of Key West’s structures were made of wood.

But that was a tall order. The already shaky reputation of Key West—referred to by some as Key Weird—as a bawdy, open town began in the late 1800s when the main business activity centered on salvaging wrecks. Suspicions ran high as to whether the wrecking crews in shallow-draft boats purposely misdirected large ships laden with goods onto jagged reefs. Many other wooden keels fell victim to faulty charts that misplaced reefs or lighthouses that often would mysteriously go dark on stormy nights.

Although the Florida Keys consist of about 1,700 islands (keys), only 43 are connected south of the state’s mainland, from Key Largo to Key West via the bridges of U.S. Highway 1 that separates the Atlantic Ocean, Florida Bay and the Gulf of Mexico. Monroe County, the southernmost county in Florida, envelopes all of the Florida Keys and portions of Everglades National Park and the Big Cypress National Preserve. Since 1990 the entirety of the Keys and surrounding waters lie within a national marine sanctuary. Key West received national notoriety when Ernest Hemingway decided that the southernmost city suited him just fine. The novelist lived there in the 1930s, allocating plenty of time when not writing or fishing to haunting Duval Street’s sordid watering holes and brothels. Key West became a clique of fishermen, rum guzzlers, and folks who didn’t care much for outsiders meddling in their affairs.

Nonetheless, by the 1950s word reached Florida’s capital city of Tallahassee that things smelled fishy in Key West, which by then had attracted all kinds of residents with liberal drinking habits and questionable character. The island became a frequent hangout for Fulgencio Batista, the Cuban dictator who, the feds knew, was playing ball with the Mafia. Even his future nemesis, Fidel Castro, dropped by the city to bask in capitalist-style leisure before he took to the mountains of Cuba to orchestrate a communist takeover.

Besides part ownerships and investments in Havana casino hotels and other coastal resorts lying a mere 90 miles south of Key West, the Mafia operated with total impunity in Cuba, the Pearl of the Antilles. Reciprocally, Cuba became a Mafia business partner completely outside the reach of the U.S. government, and it didn’t take a Sherlock Holmes to recognize that this could not occur without complicity and total cooperation on the part of Batista. And the dictator sure wasn’t doing it for free.

The Cuba-Mafia connection ran deep in Key West. Tampa Mafia boss Santo Trafficante Jr., who inherited from his dad a bolita operation in Tampa, Orlando, Miami, Key West and later Cuba, undoubtedly crossed paths with Batista if not one of his henchmen. The common denominator: The popularity among the Latin community of bolita, which gained traction in the 1880s in Tampa and was enhanced in the 1920s by then Tampa mob boss Charlie Wall.

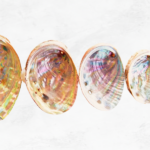

Bolita involves an illegal form of gambling often referred to as a “numbers game.” It’s a daily game in which 100 numbered balls are placed into a bag, the bag is shaken a few times, and one of the balls is blindly drawn. If your ball gets picked, you win a portion of the money pooled and the rest goes to the sponsor—in this case, the Mafia. Although most individual bets are usually a dollar or less, the simplicity of it adds to the popularity and thus can enrich the winners and bring in a steady daily cash flow to the mob. Like all forms of gambling, it can be rigged in a variety of ways. The progression here is that keeping up the flow of illegal bolita money involves making sure palms get greased, and thus the corruption element also comes into play with law enforcement and the legal system.

But essentially Batista made himself the legal system in Cuba, and he fed at the Mafia trough. Although Santo Trafficante Sr. died in 1954, as already mentioned his son—Luigi Santo Trafficante Jr.—inherited control of organized crime in Tampa with partnerships in Cuba and South Florida. Through the Trafficante connections and coordination of organized crime with Mafia families in New York City and New Orleans, business in Cuba flourished under the protection of Batista’s dictatorship. And hence all other aspects of Mafia dealings besides bolita sprouted openly in Cuba and also in Florida: casino skimming, prostitution, extortion, loan sharking, insurance fraud, and with it numerous corrupted officials. Those who tried to stand in the way quite often disappeared when fishing or on Everglades hunting trips.

In the late 1950s heroin became of interest to the Trafficantes, even though the NYC families—still controlled by old-school La Cosa Nostra bosses—eschewed it. A perfect conduit for heroin and later other narcotics into the U.S. involved Havana serving as the hemisphere’s distribution center. After Cuba received flights and shipments from various countries like Colombia and Turkey, speedboats had their hulls laden with heroin and marijuana and sped unfettered over the 90 miles across the Gulf Stream to Key West. The web of organization included the timing of trucks at the docks to haul the illicit drugs to Miami under the auspices of Trafficante mobsters and drug dealers.

Despite Key West’s diminutive dimensions of 1.25 miles at its widest point and four miles long, its population still represented the largest concentration of residents and businesses scattered throughout the chain of islands that make up the Florida Keys. In a crowded little town like Key West, rumors became facts and facts became rumors, particularly as they pertained to Mafia presence. FBI files on Key West Mafia ties and activities were opened in the 1950s and swelled through the 1960s. That was when names started turning up in those reports like Farto, Trafficante, Teamsters Union President Jimmy Hoffa and Teamsters operatives Sam “The Fat Man” Cagnina and Raimundo Beiro.

As in all small communities, a web of connections existed. Allegedly, Cagnina was a nephew of Santo Trafficante, and besides doing the bidding of the Teamsters Union he ran a crew in Key West involved in all aspects of organized crime. One law enforcement source listed Cagnina and his accomplice Beiro as cousins. Bum Farto, a lifelong Conch—the moniker bestowed on native Key Westers—could not have been ignorant of all these happenings and familial relationships, particularly considering that in 1955 he’d married Beiro’s sister, Estelle.

Even in the southernmost city of the Lower 48 states, deep dark secrets could not be hidden from the rest of the world forever, and Florida’s Governor LeRoy Collins would soon take action. But before that hammer fell, other events shook the island and the world. First, Batista fled Cuba on January 1, 1959, before Castro could arrest him. Since the inevitable defeat of Batista’s troops could be foretold months previously, he flew out of Havana to Portugal, likely with enough cash to last four or five lifetimes (he died in 1973).

Castro immediately shut down the Mafia operations and nationalized everything in the mold of the Soviet Union, which had been secretly funding and abetting his revolution. Not surprisingly and yet to Eisenhower’s horror, Castro publicly declared his allegiance to communism. The start of the Castro dictatorship also meant that the Havana to Key West to Miami drug artery no longer flowed.

The Mafia was none too happy to lose such a perfect setup. Nevertheless, things went on as usual in Key West with shipments of narcotics coming from ports other than Havana to the city and other drop points up the line of islands. But the mob’s troubles in Key West took another hit on January 1, 1961. Governor Collins made his move—the “Bubba Bust,” consisting of 40 arrests. That included local bolita kingpin Louis “Blackie” Fernandez along with his coterie of ticket sellers and accomplices; undercover cops packed up and left for home.

Undaunted, once the dust had cleared Trafficante restarted bolita operations and took control of the island’s police and fire departments. The Tampa Mafia did the same with Key West’s commission and the trucking and construction unions—the latter orchestrated by frequent Key West visitor Jimmy Hoffa. By controlling shipments of goods to Key West via U.S. 1—the only road connecting Key West with Florida’s mainland—the mob could extort local businesses. Teamsters’ money flowed into ownership of Key West resorts, a shopping center, and, as a PR gesture, a seven-figure check was donated to the local hospital.

Bum Farto weathered the storms. In 1964 as the new fire chief, he set out to prove he wasn’t merely going to keep the seat warm. With fervor and bravado, he upgraded the fire department’s trucks and gear, boosted the staff’s morale, provided free safety inspections, quickened notifications when a fire was reported, and improved fire truck response time. To feed his ego, Farto proudly referred to himself as “El Jefe,” Spanish for The Chief. Over the next 12 years he helped rescue Cuban refugees and provided them safety and comfort—hey, not even bad people are all bad. But one thing Farto didn’t know: He and his fire department were on the feds’ radar screen. One such investigation—Operation Conch—would prove to be his Waterloo.

On September 9, 1975, state and federal law enforcement authorities made their move, resulting in Farto’s arrest. He’d been caught red-handed selling drugs to an undercover agent. Besides Farto, the city attorney and 27 others went down as well—mostly those with Miami drug ties. As further details emerged, Farto was accused of using the fire station as a base of operations to sell cocaine. The news created shock waves throughout Key West and resurrected persistent rumors about Farto’s coziness with organized crime figures. His reputation and many good works spiraled down the drain.

As quickly as the ink dried on Farto’s arrest warrant, whispers centered on who else he and the others might take down with them. Sentenced to 30 years, Farto damn sure knew the fate of potential squealers facing long prison terms. The news about Operation Conch immediately spread, reaching the ears of Santo Trafficante, New York Mafiosi, and drug kingpins in Miami and Colombia. Facing either decades of decay in a cell or his corpse being eaten by sharks, on February 16, 1976, Farto put his taillights to Key West and likely drove exactly at the speed limit to Miami—his car was discovered there two months later. He’d jumped bail, a real Farto vanishing in the wind.

Did he go on the lam to another country? No records suggested such. Did he get silenced by the Mafia or drug lords? No proof of that exists. In fact, his body—like that of Jimmy Hoffa, who coincidentally disappeared five weeks prior to Farto’s arrest—has never been found. An all-points bulletin and periodic manhunts proved fruitless. The years peeled off the calendar. Anyone who knew anything about the whereabouts or getaway plans or death of Bum Farto kept mum. Finally, he was declared dead.

Whether he passed away long ago (he’d now be over 100) or made it to a safe haven is anyone’s guess. But I’ll state my theory. It’s likely that Farto was the driver of his car to Miami, where drug contacts lived. The fact that he jumped bail signaled his intent never to cooperate with law enforcement, which the Mafia realized. But at the same time, they knew if he got caught he could still do a plea deal. In other words, Farto reckoned that he needed to escape to a place offering a decent lifestyle with a new identity where no one could finger him. The Bahamian and Caribbean islands were too small to remain incognito. He wouldn’t go to Cuba because while he may have been chummy with Castro during his visits to Key West over a decade earlier, Farto realized that the new Cuban dictator wouldn’t be keen harboring an American drug fugitive. In fact, Castro might even use Farto as trade bait with the U.S.

Ergo, I believe that a former drug contact in Miami helped Farto obtain forged ID and concealed him for a few weeks. Farto then hopped aboard a private plane or boat and hightailed it across the Gulf of Mexico. I conclude that Farto ended up in Costa Rica for two reasons: It’s one of the more pleasant and stable countries in Central America, and in 1976 living outside the capital city of San Jose pretty much assured anonymity.

Guesswork aside, Joseph “Bum” Farto’s disappearance remains a mystery over 50 years later. But the evolving lure of drug money in the Florida Keys hardly ceased. In fact, it escalated, and if the players weren’t quite as colorful in name or action as Farto, the fever from suitcases stuffed with Ben Franklins infected the hearts of many notable Keys figures.

___________________________________