In a late episode of Better Call Saul, Saul Goodman beseeches his wife Kim Wexler, “What’s done can be undone.” Caught up in a web of lies and deaths, and questioning what she has become along the way, Kim has relinquished her law license, and Saul implores her to undo her decision in an act of desperation. He knows what she has worked to achieve; he knows the people she has helped. He knows that their partnership is on the line.

His plea is also an interesting inversion of a line from Shakespeare’s historic play, Macbeth. Lady Macbeth, haunted by remorse to the point of bloody hallucinations, knows there is no going back from the murderous machinations she and her husband have set into motion, and laments, “What’s done cannot be undone.” At last, she acknowledges that her cruelty and her husband’s bloody deeds are about to catch up with them. Over four hundred years later, Saul says the line even as he knows it is untrue, even as he knows that his schemes—and Kim’s guilt—have brought their relationship to an end.

Criminal couples have long inspired fascination in popular culture, in part thanks to our collective curiosity about their psychology. A single immoral mind we can make sense of. But an immoral romantic couple—Bonnie and Clyde, Aileen Wuornos and Tyria Moore, the “Lonely Hearts” murderers—unites two corrupt sensibilities working in tandem. Is it love that binds them, a connection bound between two disturbed people who have finally found their soul mates? Or is one, dominant and sociopathic, manipulating the other, who is weaker and likely to follow?

This was the speculation about the crime of the (early 20th) century—the 1924 Leopold and Loeb trial—in which two young men were convicted of kidnapping and killing a 14-year-old boy, Bobby Franks. Leopold and Loeb’s relationship was itself an object of psychological speculation: the two spent seven months planning to commit the “perfect” crime. It was also the inspiration for Alfred Hitchcock’s parlor thriller, Rope. Based on the 1929 play by Patrick Hamilton (perhaps more well-known for Gas Light, from which the word “gaslighting” is derived), it stars Jimmy Stewart stars as a former teacher, whose jovial Nietzschean/Dostoyevskian thought experiments about the “exceptional man” (the Übermensch who operates beyond common moral laws) have influenced a pair of his former students. Released in 1948, just after the conclusion of the Nuremberg Trials, Rope was a poignant reflection on the horrors to which such a philosophy leads. But the film’s main focus is a couple: the two young men, Brandon and Phillip, who strangle a classmate and place him in a wooden chest that will ultimately serve as both a temporary coffin and a table from which they will serve their invited guests—including the victim’s father—dinner.

In fiction, the couple succeeds for a time. They are the epitome of partnership: two minds operating as one. The recent streaming series, Mr. and Mrs. Smith, highlights the development of this unified thinking. It follows two single characters—played by Maya Erskine and Donald Glover—who each apply for a job as covert agents that requires them hide in plain sight under the disguise of a marriage. Having signed up for the money, they each wonder what it would be like if their partnership were not merely a cover. Initially, the excitement of the job is not as enticing as the potential relationship. As that relationship develops, then becomes threatened, the primary tension arises not in their being caught, but in preserving the partnership. They have to be aligned, mentally as well as emotionally, and it is this facet that is tested.

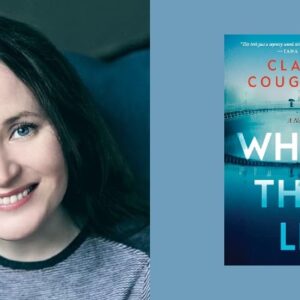

Killer couples are unified in their ambition, and they seldom have kids, at least in fiction. A child for the criminal couple sets a higher moral task. They can no longer (should no longer) be solely devoted to the partner and their joint ambitions. This tension is the premise of my own novel, All Our Yesterdays, which weaves The Tragedy of Macbeth together with some of the historical elements about the real couple that the Bard ignores: mainly, that they had a child.

Shakespeare’s play, in emphasizing this noble couple’s ambition to become king and queen of Scotland, removes the historical fact that Lady Macbeth had a son from a previous marriage. What’s more, the actual Macbeth adopted his wife’s son as his own and later made him his heir. Shakespeare’s omission of a child living in the Macbeths’ castle plays an important thematic role in the play: it eliminates the stakes raised by heredity. The son, who features in my reimagined prelude, becomes a binding force for the couple’s humanity and the potential for their ruin.

Sigmund Freud, citing his contemporary, the Austrian physician Ludwig Jekels, suggests that Shakespeare potentially saw the Macbeths as a single character, broken into two personages. They split the mental and moral ramifications of the crime: for example, Macbeth hallucinates a dagger, but that moment of madness actually transfers fully to Lady Macbeth, who suffers a complete mental breakdown along with her own hallucinations. “Together,” Freud writes, “they [Macbeth and Lady Macbeth] exhaust the possibilities of reaction to the crime, like two disunited parts of a single psychical individuality, and it may be that they are both copied from the same prototype.”

Which brings us to the inevitable: the killer couple’s relationship will fail. Justice will find them—or death. At some point their love will no longer be enough to bind them. It’s as though this intense unity—the twin minds, the divided individual—cannot possibly hold. One of them has to relent, feel the remorse they have been denying themselves, see the lack of remorse in their partner, which now makes them unideal. One goes too far; the other has to break free. We can imagine what this means for Brandon and Phillip, the two young artful murderers in Hitchcock’s Rope. I won’t spoil Better Call Saul or Mr. and Mrs. Smith except to say that, as outside observers, we are more upset by the threat to the relationship than to their lawful comeuppance.

By and large, whether it is Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, or Saul and Kim, we know the criminal couple cannot get away with it—at least not both of them. It’s unnatural, that level of intimacy. To be completely united in love is romantic, but to be completely united in the mind is psychopathic.

***