I was twelve years old when I met my first outlaw.

She was a woman whose face had graced the FBI’s “10 Most Wanted List” for her part in the radical leftist movement of the late 1960s and 1970s—not that I would have known what that meant or recognized her by name. I was an unbearably shy girl with bangs shadowing my eyes, some nameless kid she surely doesn’t remember. But I remember her.

My family had come to look at the house she and her husband had built deep in the woods upstate. They were seeking tenants and so we’d driven a long way up mountain roads to find our prospective new home, the route carrying us off paved roads onto dirt and gravel, as if the house was kept hidden on purpose. Now there I was, burst out of the car, a meek form hovering outside her bathroom door. Her husband was the one handling the house tour, and it’s possible we were very early, or very late. She’d just stepped out of the shower: a towel wrapped around her sopping-wet hair, damp freckled back and shoulders. I was interrupting. She seemed offended by my passivity: If I needed to use the bathroom, why didn’t I just speak up and say so? Something stings about this memory, exposing a flaw in my personality and some kind of life lesson I needed to recognize. Maybe this is why I’m so fascinated with stories about women who live outside the law. Women who take what they want. Women who commit crimes and refuse to be caught. Women so outside the limits of what’s acceptable in society, they’d never even bother asking.

The woman who had once been what I thought of as an outlaw was one of the leaders of an infamous group that went underground in the 1970s, after an action that left them splintered and on the run. She’d gone into hiding, living for years under assumed names in various parts of the country, sending out communiques that called for the overthrow of the government, and yet I knew none of that. Not at first. By the time I met her and her husband both, it was years later, their names cleared off the most-wanted list, their lives able to be spent in the light. I don’t remember ever seeing her again after this interaction. Still, neither of us could have guessed that her words, and the secrets she kept stowed in that house, would find a way to shape my creative imagination and the fiction I’d grow up to write.

This woman became our landlord. My family moved into that house, and there we’d live during the next two abominable years I’d spend in junior high school, an impressionable period at the knife edge of the late 1980s in which I’d find myself, lose myself, get obsessed with caustic hair metal until I was saved by a cassette tape of the Pixies, and stand up to authority in the only way I knew how: by refusing to dissect the fetal pig in eighth-grade biology.

But in the house there was a treasure trove that showed me a different kind of life. Our landlords had left behind their personal filing cabinets in the basement (along with a colorful collection of dishware we were welcome to use and did, a jar of loose coins under the sink, and the buried shell of a long-deceased pet turtle). Those filing cabinets were not for us to look through. And yet, what is a girl in isolation to do when her parents were at work, pre-internet in a place so remote we didn’t even have television reception, except go fishing through things I’d been explicitly warned were not for me? There, at the row of filing cabinets under the basement staircase, I read all the years’ worth of saved correspondence. I read the typed communiques. I read the newspaper clippings. I learned about living underground (the paranoia, the near misses with suspected feds). In sifting through those drawers, I’d wrenched open a window without asking. And because of that I learned things no one would dare teach me. I drank in every page and picture. I absorbed. And, like the character-driven novelist I suppose I was destined to be, I wondered about the motives and secrets of the people I read about, and I imagined myself in their shoes.

I find it interesting how the most random of occurrences in the distant, most prickly recesses of your childhood can shape the work you create as an adult. Surely this is why as a writer, and as a reader, I find myself drawn to characters on the defiant margins. A woman on the run from the law holds a special kind of fascination for me when it comes to a character. This goes beyond an appreciation for an “unlikable” female protagonist and all she may offer the story in terms of complexity and exploration into the gray. (Characters don’t need to be liked; characters just need to be compelling.) A female outlaw character, a woman at the edge and often with nothing to lose, has the potential to derail expectations. To raise the stakes and heighten the tension. To wake you up.

Decades after I lived in that house, and a handful of published novels later, I recognize that some of the same whispers of intrigue and questions of morality that I was grappling with as a girl elbows-deep in those basement filing cabinets have found their way into my fiction.

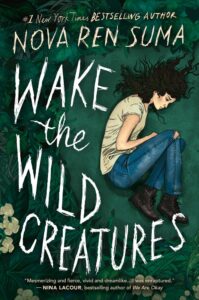

My newest novel, Wake the Wild Creatures, is a coming-of-age story of survival set in a community hidden in an isolated part of the mountains, admittedly near where that house had stood. The girl narrator is raised by her fugitive mother to be distrustful of the outside world. Her mother has been accused of murder in the towns at the bottom of the mountain, yet my narrator believes her actions were justified. Wake the Wild Creatures begins the night that lights pierce the forest and authorities cross the perimeter in search of her mother. Both my protagonist and her mother are captured, and the core of unravelling the narrator’s story lies with understanding who her mother is and why she did what she did.

One draw of inventing a woman outlaw in the pages of your fiction is the gripping story pathways that emerge. She can be an enigma, an open question, a walking wound. And we fiction writers sure like to pick at and gouge open the most compelling of character wounds. In my own novel, I was drawn to the idea of narrating the story from the outside and trying to understand a woman who’s killed and run from the law and why she’s done it. Much of the story circles around that understanding, but there comes a point when the messy, blurry truth needs to be revealed to my protagonist.

Other books show the way. As I was writing, I was struck by novels that captured female fugitives on the page. Some allowed me to see methods of accessing character motivation in the ways I craved, and others left me enthralled by a healthy shield of mysterious haze. All engaged with the idea of a woman outside the law in different time periods, places, and approaches.

The protagonist in Anna North’s alternate history Outlawed takes on the genre of an Old Western in 1894 through the piercing voice of a female outlaw, Ada, who after being forced to marry at a young age refuses the roles and feminine expectations set out for her and runs away to join a crew of bandits. Another Western, this time set closer to today during pandemic lockdown, Ivy Pochoda’s Sing Her Down showed the intense, heart-pounding showdown in downtown L.A. between Florida and Dios, a pair of women who jump parole and end up on the run and in frightfully intense and incendiary confrontations with each other. And in another landscape and time period, the character of Jenny in American Woman by Susan Choi is a young radical in the 1970s in hiding after an act of violence against the state, and takes as inspiration the Patty Hearst kidnapping. There we can grapple with the inner motives, doubts, and troubles that come with a character attempting to live her principles and getting too far in.

However, the fugitive in my novel is not the protagonist herself but her mother. In Olga Dies Dreaming by Xochitl Gonzalez, my fascination as a reader centered on the protagonist’s anger toward her mother, Blanca, who had left her young children to commit herself to the revolution for a free Puerto Rico, and comes back into their lives in a shocking way during the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. There is a mother in hiding in Celeste Ng’s futuristic Our Crooked Hearts, and one of the elegant surprises of that book was the way the narrative passed over to her midway through the story, so at first we saw Margaret, a fugitive from the authoritarian government and a poet who knows the power of words, only through her young son’s eyes. And then the story flips and lets us in. Lastly, I’ve long been struck by the final electric notes of The Mars Room by Rachel Kushner, when her protagonist Romy grabs her singular moment to break free from imprisonment where she’s facing two life sentences for murder, and forced to be separated from her child, and we follow her attempt to flee as her narration soars to complex and even cathartic revelations on the page.

It’s clear that something got caught inside my overactive imagination when I was twelve years old and learned about people who choose the life of an outlaw. Writing fiction—and this book in particular—has been a way of exploring and embracing my own invention.

The “woman on the run” is an archetype of interest in fiction of all genres, but as I found when I was writing Wake the Wild Creatures, there’s something all-consuming about a woman on the run not in fear from others but from what she herself may have done. That most provocative of characters, the female outlaw who refuses to give up herself or her secrets, will forever drag me in. In the end, will she be found and punished and crushed under the weight of what society deems is wrong—or will she stare down the price of freedom and choose another path instead? My novel is one story among others that attempts to answer this endlessly enticing question.

***