Crack cocaine came to New York City in the mid-1980s and within months the already struggling metropolis was under siege by a new breed of junkies and dealers. During the decade before, the graffiti covered city was on the verge of bankruptcy, but beginning in 1980 under the reign of Ronald Reagan’s dire presidential policies and budget cuts, poor communities were further destroyed. There were few jobs or social programs, and many desperate young men became coke/crack sellers hoping to improve their personal socioeconomic status. Devastating their own neighborhoods, criminality ranging from broad daylight dealing and shoot-outs to discount prostitution became the new normal.

“It was shocking to me how many women got caught-up in it so quickly,” remembers journalist/novelist Thulani Davis, who was an editor at The Village Voice back then. “I was living in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, and one of my neighbors started smoking it. I could smell the fumes coming through the walls.” It also didn’t help that crooked police precincts were paid off to turn a blind eye to the 24-hour chaos while aggressive dealers, many in their teens and early twenties, modeled themselves on Al Pacino’s slimy Scarface (1983) character and became sellers of destruction in an effort to build wealth and, hopefully, escape the bleakness that had crept into the community.

Decades later, when I discovered the Harlem photographs of Matt Weber his stark, often bleak images of my community during that era transported me back to those days of drugs and decay. While my block of 151st Street between Broadway and Riverside wasn’t as dilapidated as some, it still felt as though there was a black cloud hovering overhead and the end was near. Former journalist Barry Michael Cooper, who co-scripted the influential crack film, New Jack City, was the first writer to document the rise of the deadly drug in his brilliant Spin article Crack published in 1986.

“Crack is the latest drug in New York, and its use is becoming epidemic,” Cooper wrote. “These white pellets of prepackaged freebase (cocaine in its purest form) are extremely frightening. Frequent users—peer-pressured 13-year-olds to 60-plus grandparents—don’t associate its use with the savage addiction of heroin or the hallucinogenic insanity of angel dust, its two predecessors in Harlem’s crippling drug trilogy. But, in the last year, crack has become the drug of choice; the exhilarating rush of its 5-to-15-minute high brings a distorted sense of power, a king-of-the-hill nirvana.

“Like Huxley’s ‘soma’ in Brave New World, crack is, for many, escape, booster, stabilizer, and status quo. Known on the street as ‘the white genie in the bottle’ (it is sold in vials), a rub of the crack lantern grants temporary residence in the dreamstate of your design.”

That story, which took place along the long stretch of 145th Street, was like reading the warning label on a bottle of poison. Later, that same neighborhood would serve as the backdrop for Cooper’s own New Jack City (1991) as well as Jungle Fever (1991) and Paid in Full (2002), co-written by Thulani Davis.

For those crack new jacks, who made more money than their nickel bag of weed predecessors, the ghetto dream was to graduate from corner boys to bosses who were “paid in full,” clocking dollars, making that paper.

Uptown, the “big money” made from selling the (allegedly) government sanctioned drug seduced many into the lifestyle of dealing, with some hoping to join the pantheon of legendary Harlem gangsters that included Nicky Barnes, Frank Matthews, Guy Fisher and Frank Lucas. For those crack new jacks, who made more money than their nickel bag of weed predecessors, the ghetto dream was to graduate from corner boys to bosses who were “paid in full,” clocking dollars, making that paper. Being “paid in full” soon became a mantra for young Black men who believed that street life was a sweet life, and an escape from their lives of poverty. Of course, no one stays a bad boy forever, and, if they were smart, they’d go legit sooner than later or die trying.

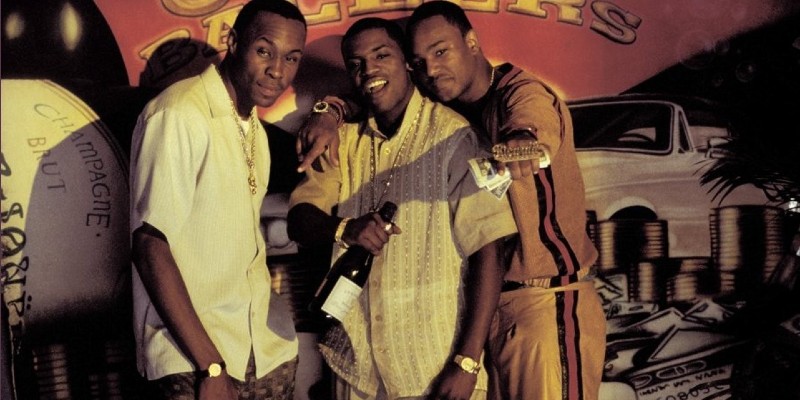

Around my way there were a few infamous crack crews that included the Jheri Curl Gang, the John Johns and the Do Wops. There was also the famed homeboys Alberto “Alpo” Martinez, Azie “AZ” Faison and the late Rich Porter, the trio whose story was used to build the brilliance that is the film Paid in Full. Played respectively by Cam’ron, Wood Harris and Mekhi Phifer, the 2002 flick is one of my favorite films in the genre of ghetto gangster movies.

Unlike the flashy prototype New Jack City, whose characters and situations were broader and more melodramatic, Paid in Full concentrated on a more personal story in a neo-realistic style that was a cautionary tale without being corny. Still, while those cats became street stars in the ‘80s, I didn’t know they existed until years later when I saw the young men in vintage photos on the covers of magazines (F.E.D.S., Don Diva) and heard their names in the lyrics of LL Cool J (“New York Gangstaz”), Jay-Z (“There’s Been a Murder”) and late Harlem rapper Big L (“American Dream”). Produced by former Brooklyn-based crack dealer Jay-Z and former Roc-A-Fella partner Dame Dash, the movie was the feature film debut of director Charles Stone III, who would move on to more mainstream fare including Drumline and Mr. 3000. Previously Stone had been the vision behind the Budweiser’s goofy Whassup commercials as well as cool music videos for A Tribe Called Quest, The Roots and Living Colour, whose guitarist Vernon Reid contributed to the Paid in Full score.

The screenplay was based on the writings of AZ, which was later published as the book Game Over in 2007. In the beginning of the movie, AZ is shown as a former dry cleaners clerk who goes from working for chump change to clocking big dollars when he reluctantly enters the drug game. “AZ really wanted to send the message that that life is not what to do with your life,” recalls co-writer Davis, who currently teaches at the University of Wisconsin and recently completed the upcoming history book The Emancipation Circuit: Black Political Organizing after the Civil War. “He insisted that some of the mundane daily things in these people’s lives (courting a future girlfriend, showing a little brother how to clean his sneakers, eating Chinese food with friends) be really present so the audience could identify with them as real people, not types.” According to the street corner gossip, in their prime AZ and his friends made between $50,000 to $100,000 a day, and spent their green throughout Harlem.

Although their hangouts were foreign to me, my younger brother Carlos, who rolled in that life for a few years, schooled me on places like the Rooftop, Bombers and Willie Burger’s, where they ruled. There were many nights when the playas were content to cruise and chill in their cars. Although many didn’t have a driver’s license or insurance, but that small detail didn’t get in the way of their passion. Having paid car dealers with bags of cash, their luxury rides and high-end stereos became important status symbols on the street. As seen in the documentary 2003 Game Over (produced by AZ, whose book shared that title four years later) these guys were serious about their rides, cruising through the hood in tricked out cars (Benz’s, Jag’s, BMW’s,) that were designed with tinted windows, gleaming rims and stereos.

Most of those cool car boys didn’t drive far in their shiny rides, but were content to style and profile in front of their favorite local spots which could be the front stoop, a club, the corner or a clothing store with Troop, Pelle Pelle and 8 Ball jackets hanging in the window. Meanwhile, the booming system soundtrack for those moments was always important and the bass-heavy music played inside the car was usually the latest rap or soul, the banging records that reflected the times.

* * *

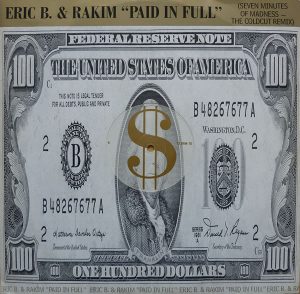

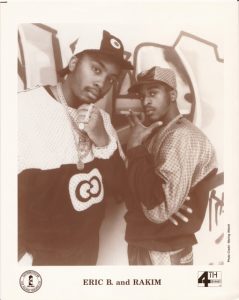

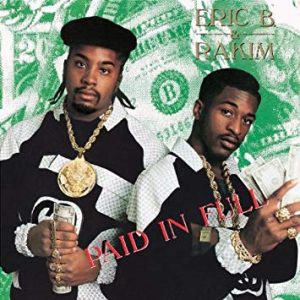

1988 is often cited by hip-hop historians as rap’s golden moment, but the year prior was also filled with dope beat symphonies that included Just Ice’s rock hard “Going Way Back,” the b-boy boogie of Public Enemy’s riveting “Public Enemy No.1” and the gangster swagger of Boogie Down Production’s minimalistic Criminal Minded. One of the choice album’s of 1987 was Eric B. and Rakim’s debut masterwork Paid in Full. Eric and Ra began their partnership in 1986 with the stellar double single “Eric B. is President/My Melody.” Combining the diamond shine lyrical brilliance of Long Island-based rapper William “Rakim” Griffin Jr. over the rough beats and scratchadelic fury of Queens native Eric B. (Barrier), whose government name is Barrier, the album soon became a crack dealer soundtrack.

As an album that would change rap music forever, Paid in Full featured the illmatic duo flexing their skills with icy seriousness, a truckload of sampled James Brown (& J.B.’s, Bobby Byrd) sounds, lyrical depth and poetic precision made them instant legends. The duo might’ve looked like drug dealers themselves, but in the studio they transformed. Juice Crew leader and producer Marley Marl engineered the single, but, in the beginning, wasn’t impressed with Rakim’s slowed down rap style. Soulfully jazzy spitters from Nas to Erykah Badu to Kendrick Lamar have cited Rakim, also known as “the God MC,” as their guiding light.

“Eric B. & Rakim sounded so different than anything that came before it,” producer Dr. Butcher explained to Goin’ Off: The Story of the Juice Crew Cold Chillin’ Records author Ben Merlis, “Marley and (MC) Shan would stand in the kitchen and laugh between Rakim’s vocal takes. Why wasn’t he shouting the lyrics like everyone else?” Though Marley had his doubts, the rest of Planet Hip-Hop loved his flow. “Rakim was the first rapper who used his voice like a musical instrument,” former Yo! MTV host Fab Five Freddy explained. “He was like Miles Davis and his sense of poetry gave the words a real essence. People felt what Rakim was saying on a deeper level.”

Released on the independent Zakia Records, an indie label owned by Robert Hill, the 12-inch single of “Eric B. is President/My Melody” was a hit. After the single’s success, label owner Hill sold their contract to Brit record man Chris Blackwell and signed the duo to an album deal with Island Records subsidiary 4th and Broadway, which was also the label’s address. Rakim and Eric later went to Power Play studios, located in Long Island City, and rushed to create a full-length album. “To me, it’s like yesterday,” Rakim said in 2016 when I interviewed him for the Philadelphia Weekly. “Paid in Full was the first thing I ever did, so it’s one of the most memorable things of my career.”

As a writer, Rakim was inspired by John Coltrane, Maya Angelou and the images of Gordon Parks. The title track, which dealt with him rapping about how to get money (“Thinkin’ of a master plan, ‘cause ain’t nothin’ but sweat inside my hand/So I dig into my pocket, all my money spent/So I dig deeper, but still coming up with lint/So I start my mission, leave my residence thinkin’, how could I get some dead presidents?”); the lyrics became gospel to many street players hoping to rise within the glamour profession of the crack trade.

“We had rented the studio out for the whole month,” Rakim said. “We would go in a 7 or 8 in the evening, if we didn’t have to be there early. I would stay until 7 in the morning.” They soon emerged with bangers “I Ain’t No Joke,” “I Know You Got Soul” and “Move the Crowd,” but the album took some time to make. “Rakim was so creative, but he couldn’t be rushed,” former 4th and Broadway A&R director Kookie Gonzalez recalled. “While writing the song ‘Paid in Full,’ he got writer’s block. Unfortunately, we had to take the album away from them before he felt it was finished.”

According to Eric B., whom I interviewed in 2012 during Paid in Full’s 25th anniversary, “The phrase ‘paid in full’ was just something that me, Rakim and Stevie Blass (Rakim’s musician brother) used in the studio all time.” Listening to his friendly, but gruff voice on the phone, I was reminded of the stony image he once projected on album covers and in videos. Eric always looked more ready for battles than interviews. “Stevie would laugh and say, ‘We gonna get paid in full.’ Those words became our vision and our mission.”

“Stevie would laugh and say, ‘We gonna get paid in full.’ Those words became our vision and our mission.”

Growing-up in East Elmhurst, young Eric Barrier got into hip-hop while hanging-out at 127 Park (aka Booty Land) with a crew of DJs known as King Charles, whose star spinner was a dude named Vernon. “When I was a kid, I became an equipment carrier,” Eric remembered. “These guys had a Richard Long system that was designed for clubs, but they played it in the park. I’d be standing behind the rope studying what Vernon did on the turntables and I knew that’s what I wanted to do.”

A few miles away in Wyandanch, young Rakim was listening to jazz with his parents. Sometimes, other relatives took him to the Bronx to check out original school pioneers Cold Crush, Grandmaster Flash and Grand Wizard Theodore. “There would be a certain feeling I would get when the emcees came on,” Rakim recalled. “By the time I was eight or nine, I knew what I wanted to do.” Changing his name to Rakim Allah in 1985 when he joined the Nation of Gods and Earths, he and Eric B. were introduced the same year.

Paid in Full was released on July 7, 1987. In the Ron Contarsy photograph on the cover the duo wore thick gold chains, fly gear and fists full of cash, the image was designed to inspire. “I wanted to show our wealth and independence through jewelry, cars and clothing,” Eric B. said. “We went to Dapper Dan’s and got our clothes.” Featured in Sacha Jenkins’ 2015 doc Fresh Dressed, Lisa Cortes’ upcoming The Remix: Hip Hop X Fashion and the designer’s own 2019 autobiography Made in Harlem, Dan was an uptown based fashion originator whose pricey bootleg clothes featuring top shelf logos (including Gucci, Louis Vuitton and Fendi) was worn by various ghetto superstars, both men and women, including Mike Tyson, Knicks players, rappers Big Daddy Kane, The Real Roxanne and Salt-n-Pepa.

Eric B. and Rakim wore Dan’s unauthorized threads in their promotional photos, videos and on the album cover, which reminded me of the ghetto glam hood Polaroid photos that folks used to take at hip-hop clubs the Disco Fever, Union Square, Latin Quarter, Broadway International and the Rooftop. The kind of picture you might stumble on twenty years from the day it was snapped, if you lived that long, and marvel at how cool you and your crew looked. Photographer Ron Contarsy recalled, “Those guys were very chill. I remember a couple of the Beastie Boys came by the shoot. The back cover was taken at the Jacobs Javits Center, which had just opened the year before.”

As author Ben Merlis wrote, “The whole thing was about fame, the Dapper Dan suit, the gold chain. It was all part of one thing.” Eric B. and Rakim became worldwide superstars and released three more studio albums, but dissolved their partnership after releasing Don’t Sweat the Technique in 1992, and didn’t reunite until 2018. The album went gold and made Rolling Stone’s list of “500 Greatest Albums of All Time.”

* * *

In 2002, fifteen years after the release of Eric and Rakim’s debut, the album’s title was sampled for the urban gangster film based on the fast lives and sad endings of Alpo, AZ and Rich Porter. In the movie, none of the real names were used. AZ became Ace, played with simmering intensity by Wood Harris. From the opening scene we see the key cats cruising down 145th Street in their sleek vehicles and gathering in front of Willie’s Burgers, the story was told from his dreamy perspective with the film opening with a Brucie B. mix-tape blaring the title song.

Paid in Full is mostly told as a series of Ace’s flashbacks, his reflection of the good times and bad on the Harlem streets. Wood Harris, who would go on to portray Avon Barksdale on The Wire, played Ace with a sense of shyness, wonder and melancholy. “In real life, AZ was very accessible and easy to talk to, but he was also very introspective,” Thulani Davis says. “He was into numerology and very spiritual. AZ is very low-key. Unlike others in that business, he didn’t want to be in the spotlight.”

“He was into numerology and very spiritual. AZ is very low-key. Unlike others in that business, he didn’t want to be in the spotlight.”

However, the spotlight was the only place Alpo wanted to be. Played in the film by rapper/Harlem native Cam’ron in his acting debut, he played the crazed live-wire Rico (Alpo) with pure intensity. There’s always that one cat in the crew who can scare you to death, and Rico was that guy. In one scene he’s aggressively challenging his friend to shooting a paper bag basketball across the room for $10,000 while in another he’s showing a sex tape of himself in public and, later, drags a rival out of the window of a parked car.

Rico was unpredictable and Cam’s performance was over-the-top and bordered on manic. His hyper-as-a-heart attack style was reminiscent of Richard Widmark in Kiss of Death or one of James Cagney’s crazy gangster (The Public Enemy, White Heat) roles. “Cam’ron was like that 24/7,” Davis says. “Sometime I didn’t know if he was acting or not, but he loved doing it.” Writer Quatoyiah Murry wrote in a 2015 post on her blog The Cinephiliac, “The MVP goes to Cam’Ron as Rico. Cam is so great in his role, so unbelievably dastardly dumb and crooked that it’s chilling. I questioned multiple times throughout the film if Cam is a legitimately great actor or if the role was so personal that he channeled it effortlessly.” While Cam’ron was able to translate that energy to the mic, he was never again that dynamic on screen.

Actor Mekhi Phifer played Mitch, the drug dealer with a heart of gold based on Rich Porter. While Money Makin’ Mitch is about the street life, he’s also devoted to his mother and little brother, who in the movie was played by Remo Greene. Yet, for all of Mitch’s juice, when the boy was kidnapped and tortured, there was nothing he could do. Of the three main actors, Phifer was the most polished, but no less captivating as he tried to hold on his family and sense of self, only to lose both.

Author Chester Himes called his Harlem crime novels “domestic fictions,” and, because of amount of time Paid in Full spent with the families of Ace and Mitch, this flick could also adopt that label. Paid in Full had no problem showing the ill effects that a drug dealing lifestyle can have on innocent family members just trying to make it through another day without getting popped by a stray bullet. In fact, most of the misery and blood spillage came from friends (Kevin Carroll as Calvin was wonderful) and family.

Furthermore, while these characters were “paid in full,” the money wasn’t spent for anything more than cars, clothes and jewelry with zero being invested in stocks, bonds or real estate. In the end, though many Benjamins richer, they were still sitting in their mom’s drab apartments with their loot in safes by the bed. Though they strived for better lives, not much changed in their small world. In the end, though all had “enough dough to bake biscuits for the projects” and buy expensive things, it also brought them much pain, sorrow and death.

By 1990, Rich Porter was dead, Alpo, who years later confessed to his friend’s murder, was in prison, and AZ rebounded with a rap career, recording and performing with his group MobStyle and several entrepreneurial projects. A few years later, the “paid in full” capitalism of Eric B. and Rakim’s song and drug dealer chic of Alpo, AZ and Rich Porter inspired the ghetto fab personas of Puff Daddy’s decade defining Bad Boy, Jay-Z’s dope boy dream Roc-A-Fella and many other bosses who never stood on street corners, bottled-up bricks, cooked crack or ducked bullets fired from the 9mm of a so-called friend.

Paid in Full is currently streaming on Netflix.