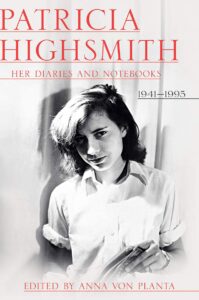

This draft of “The Bloomingdale Story” was written by Patricia Highsmith in 1948. It would later be expanded and significantly reworked before being published as the novel The Price of Salt, later titled Carol. The draft is included in the newly released book, Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks, 1941 – 1995, published by Liveright Publishing, which has made it available here. Notes presented in the right margin were made by Highsmith upon revisiting her notebooks at a later date, accompanied by explanatory notes from her longtime editor, Anna von Planta.

___________________________________

12/9/48

I see her the same instant she sees me, and instantly, I love her. Instantly, I am terrified, because I know she knows I am terrified and that I love her. Though there are seven girls between us, I know, she knows, she will come to me and have me wait on her. (For our eyes have clung too long, she in the same pensive attitude of judging the dolls behind the counter, behind the glass, but her eyes fastened to mine as mine are to hers – as if we knew each other. And my entrails went tumbling down, and my blood went rising to my head, and I sweated, before I moved.)

She wants a doll‘s valise. She points casually, leaning on the counter. She wears a supple fur coat, an unobtrusive hat, she has blond hairs, powdered, on her upper lip, a strong, full mouth, and those wonderfully knowing, intelligent grey eyes in which I see so much wise laughter, – so much tenderness, for she never looks without seeing.

I advise her to buy her doll‘s clothing separately, for those we have are not well made. Casually she buys a $17.50 alligator valise, and wants it sent C.O.D. Her name unfolds beneath my pencil point like a wonderful secret I shall never forget.

P. of S.

(ed. note: To be cut. One of many instances of Patricia Highsmith

revisiting her diaries and notebooks at a later date.)

”You‘re giving me the one on display? They‘ll have a fit, won‘t they?”

”It‘s much easier than finding another,” I murmur, and wish I had said the arrière-pensée ”This place isn‘t called Bloomindale‘s for nothing.”

As I write, a D.S. comes over to me and informs me I am wanted in the D.S.‘ office. And I blush more hotly than before. My lady stands within ten inches of me!

”Now don‘t make any mistakes,” she cautions me lightly.

And I wish with all my heart, that she had said, ”What are you doing for lunch,” for I can hear the tones of her voice saying it. ”What are you doing today for lunch?” Why doesn‘t she? I am abashed by my cheap skirt, drab black blouse, humiliating moccassin shoes, as I take her the top of the green C.O.D. slip. She stands at the doll‘s clothing counter.

And a moment later, though, when I look again, she has returned. She buys a doll, still looking at me, and as I bend to write her address once more, pretending I have not memorized it, she I hear, in those tones I had anticipated, just as I had anticipated, though not in those precise words: ”What do you do about lunch around here?”

And when I hesitate, for it is an ambiguous question: ”What are you doing for lunch today?” with her eyes looking down through the glass counter.

“I can go anywhere,” I reply softly, frenzied lest Miss Henderson be even watching us.

”Shall I meet you at the Fifty-ninth Street exit?” She looks up and gives me a small quick smile, and the low pitched voice again: ”We might have something to eat together.”

The rest of the morning, my fingers trail long faint lines below their convulsivel pressed forms, and I show dolls with indefatigable patience and total stupidity of memory. I make the best possible toilette with my cold, miserable, trembling hands.

”What‘s your name?” she smiles plesantly as we walk onto the sidewalk.

”Lisette Freyer.” No, I have not been working here long. I live alone in a room on Sixty-fifth Street. My parents are dead. I am eighteen, and just out of high school.” I do not tell her it is an orphanage high school. I do not tell her about Sister Penelope, whom I adored and think of constantly, a pretty, sad young sister with a pale face, calm grey eyes, a pointed chin. Because since this morning, Mrs. Senn has thrust Sister Penelope far away, far below her. We go to Longchamps and Mrs. Senn suggests I have an Old-fashioned cocktail like hers. Then another. I stare at her lipstick: it is in a gold case – real gold, I know, like a jewel – and shaped like a long chest, with straps and metal corners. I look into the darknesses between the raised portions of the chest as if they contained a secret for me, and she says:

“What do you like to do in your spare time?”

Shall I tell her I like best to dream? That I weave small basket rugs, sometimes make sketches, often take long slow walks, most often read, but that I like best simply to dream at my window and certainly to dream at every task, even behind the counter at Bloomingdale‘s? But I know I do not have to tell her. She knows. I love the warmth of her drink inside me, but it is like her to swallow, terrifying, difficult, strong in the mouth, not easy.

”You‘re a very pretty girl,” she says, after the waiter leaves us, with the two steaming plates, buttery smelling, of poached eggs on spinach

It is as if she spoke of a doll, so casually she tells me I am pretty. ”I think you are

[I set her age at thirty-five, an exciting thirty-five.

Already I think how happy her husband must be.]

(ed. note: PH’s comment, when rereading her notebook.)

magnificent,” I reply with the courage of my liquor not caring how it may sound. For I know she knows, anyway. As we eat, that fantasy of ideal of sensation idea of which I have had only the faintest hints from time to time, beginning so long ago I cannot remember, becomes a definite wish: I want to lie in bed and have hot be brought bring hot milk. I want her to bring me hot milk! It is on the tip of my tongue to say it, I feel, because of the liquor, I bite my tongue, but I know it is as remote as ever from my utterance. To lie in bed. Yes, even her bed! Hers! To be a little sick, (sick enough to suffer, too!) too sick to do what I ordinarily do that day, to be put to bed and be brought hot milk –

“How is it you live alone?” she asks wisely, tenderly, and before I know it, I have begun told her my life story.

But not in tedious detail! In six sentences, with humor, as if it all mattered less to me than a story I had read! And I succeed in making her smile. I see her noticing my nails – short, fine, clean, but innocent of the manicurist, my rayon blouse of pastel pink, my commonplace little sports wristwatch. (What a bore! I think) <arrow to beginning of paragraph>

“What do you do on Saturdays?”

“I relax,” I smile. ”What do you do?”

(Why do you drink it? If people anyone knew the answer to that there

would be no alcoholics.)

(ed. note: PH’s comment upon rereading her NB.)

“Relax. Would you like to visit me?”

I must go then. I live until Saturday on the thoroughly impossible hope that she will return and buy something else in the toy department, or even revisit me. I work badly but happily, with the indefatigable patience.

She comes for me in her car at Sixty-fifth Street and Third Avenue Saturday morning at ten thirty. I suspect she has not called for me at my house because she does not wish to embarrass me by letting me see that she sees its ugliness. And we drive to Ridgefield, New Jersey. The Lincoln Tunnel is the most exciting. I wish – I wish it might cave in and kill us both, that our bodies might be dragged out together, and I am more insane than when I drank the two Old-fashioneds.

“No one‘s home – except the maid,” she remarks as we get out on the gravelled drive that is in the form of a semi-circle in front of her house.

She shows me over the house a little – the bathroom, the kitchen – as if I am going to live there with her, and yet oddly, as if she did not think herself that I was going to live there.

“My bedroom,” she says, as we stand on the threshold of a room of flowered chintz upholstery, green woodwork, a great splash of red somehow over the dressing table, and throughout a look of sunlight, although actually no sunlight comes here, and it has the pale cool shade of early night. The bed is a double bed. And there are military brushes on the dark wood bureau across the room. I glance in vain for a picture of him.

“Do you have any children?”

“No,” she sighs, touching her short, curled brown hair, twisting her beautiful intelligent red mouth. “No, I haven‘t. Would you like a Coca Cola?” She opens the a panel in the hall, and the faint hum of a small refrigerator comes louder. Through all the house is no sound but those we make.

(ed. note: In the Bloomingdale Story, the future Carol is not blond.)

We walk about the lawn, the garden, toward which she seems indifferent, and soon it is time for lunch – a cold cut lunch in the kitchen, without drinks. How foolish a drink now! How more enchanted could I

be?!

“What do you want to do?”

“I am happy.” I reply. And when she asks me another casual question about the store where I work, I tell her a funny anecdote I had already prepared carefully.

She leaves her lunch and mixes a tall highball in a big glass. After lunch, she has another. She takes me into the sitting room, insists I play the piano, whatever I know, and listens absently though raptly as I play a little Mozart I have not played in over a year.

“Are you tired?” The question is not of now, not of but of always.

“Yes.”

And then, she comes closer to me, touches me with her wonderful hands – a little veinous, flexible, strong, red nailed – and kisses

Me, first on the forehead, a kiss of slow pressure, then – gently – on the lips. “Come with me.”

And she takes me to her room, commands me to get undressed. “You can sleep on my side,” she says, and puts me to bed, as if I were a child, in a pair of her p an old night-gown of hers. “I‘m sorry I haven‘t there isn‘t a bed in the other room,” she says, and I feel immediately she has had a child and lost it, though I know I shall never be able to ask her.

“How old are you?”

“Eighteen.” How old it sounds! It shames me! It is older than eighty-one!

“What would you like?” she asks as she gathers me in her arms. She sits beside me on the bed. I am too ecstatic to reply. I desire nothing else! Even the hot milk now seems heaping riches upon riches, an absurd excess! ”What would you like!”

“Nothing more,” I murmur.

I worry greatly about her restlessness. She gets up, sits down, gets up again and walks away and lights a cigarette. The cigarette makes me smile somehow. I love the cigarette, love to see her smoke.

“What would you like, a drink?”

I know she means water. I know from the tenderness in her eyes, the gentleness in her voice, as if I were a sick child. And then I say it: ”Some hot milk.”

And lie in tense-relaxed, expectant-fulfilled state with my tongue at the top of of my mouth until she reappears. Mounting the steps and reappearing with my hot milk in a cup in a saucer. She has let it boil, she says, so it has a scum on it, and she apologizes. But I love it, because I know this is just what she would do. Then she asks three questions about me now, my happiness, about the store, and against my will, I tell her in a great burst all that I hate, of my loneliness, and at last I weep inconsolably, and by the time I can control myself, [I] am already anxious lest her husband come home, for it is already darkening.

And she knows, of course, and without word we signal to each other we must be going. I do not mind at all when she puts me on the train instead of driving me home. Could I have borne her making the trip back in the car alone at night?

How does the weekend pass? I long for the store again, for this is my only hope of her. There was not a minute I did not see her in my mind that weekend! More than the center of the world. There was no world without her. Then that which I had always desired came to be: everything else. The great flat streets, the counters of merchandise, the hurrying armies, the milk bottle dropped and broken in the sink, my own room itself, my bed, became unreal, depressed somehow, unimportant.

She came again. She invited me to her house again, changed her mind and suggested we go to the Metropolitan Museum, changed her mind again, and drove, smoking, up the Henry Hudson Parkway. And then, weeping – I was too discreet to ask her why, to pretend I did not notice either, handing her a paper tissue – she took me home. I began the weekend without her. I lost her car in a blur of tears at the end of the block, and mounted my stairs with the trinket I‘d bought to give her still in my pocketbook – the naked doll with the long hair.

(End with X-mas? The woman in her riches, the girl

with a big present that makes her cry.)

(ed. note: Comment added by PH while writing the story.)

(ed. note: From here onward, the text is more like notes for a book,

with the young protagonist of the story reverting back to the real PH.)

Note: the woman remains the same throughout.

I can envisage an entire book, with enough human play on the seventh-floor toy department. Interspersed with the rrrrrrrrrr of the little toy train with the blue smoke puffing from its smokestack rounding and rounding the U-shaped track, through the tunnel, pulling eternally its load of logs and mineature coal to

nowhere.

The constipation of the worker, until she cannot eat any more.

“Miss H.” says the D.S. with mild horror, ”You‘re not closing up, are you? We have customers and it‘s only quarter to six.”

(ed. note: Here PH is back as the young protagonist.)

Rrrrrrrrrrrrrr – the little toy train is still moving!

“Do you have the dolls that wet?”

Note: She looks at the corners of thing[s], the texture, the color of a suitcase in close view, wanting desperately do get something out of it. She thinks impatiently, ”What an

idle minded idiot I am!

A woman is triumphant at having found our doll blanket, and seriously discusses the doll‘s snowsuit she will purchase at the next counter.

The lesbian type girl at the doll‘s dress counter says, she “Ah, there‘s my little friend,” pointing to the boy boxer doll.

“But nobody buys boy dolls,” I say, “nobody likes them.”

“I like them,” she declares.

The stocking smashed on the stock roller corner, the humiliating double runs, broad ones, the remainder of the day.

The few people who have time, who think as I do, with whom I enjoy shopping as they drift from counter to counter.

And the pingpong ball bouncing and bouncing into one of the three holes it must fall into in its score board. The clatter, bang, clatter, the mechanical drummer with his toothpick size drumsticks.

The serious, serious D.S., who are the funniest, saddest of all. The smashed, soiled cloth carnations they wear in their buttonholes. Yet even in the two young men who have been here only two weeks, one can see the making of executives, and it is a terrifying process to watch indeed. A gross error is discovered in some miserable sales girl‘s cash registering, but the young undersized D.S. shows no loss of self-possession, no humor, no mercy and no chastisement except that bitterest of all – cool indifference to the sweating girl‘s possible emotions as a human being – and opens the register, ticking off the errors with his pencil on the white roller of register recordings like a medical specialist poking deliberately and into one‘s vital organs.

A gay horse, painted lavender, star-studded, grins and leaps from a supporting pillar – for whom? Who has time to look at him. Did there ever walk a human being between these counters lost in the toy world for which the toys were created?

(Saddest of all are the sad people who buy dolls. Those who patiently, desperately, forlornly release their five dollar bills on the counter and hurry away to somewhere.)

(Happiest of all are the proud young mothers, one a pretty blond girl with “my two daughters – the four-year old knows a little bit how to take care of things, but my two year old! –“) Happiest of all are the young couples – I saw three or four – who come together to buy the first important doll for their three-year old, who share the happiness, will share the vicarious pleasure of her pleasure when she sees it Christmas morning.

The young D.S., the grinning young thing, oh-so-pleasant, with blond hair and harlequin glasses, who tells us we must sell the battered $24 suitcase, because tomorrow it‘s got to be marked down, and the department will take a $3 dollar loss if we don‘t. She is climbing up to D.S. status. She will one day make $45 a week! (The girls whisper – ”Don‘t let her hear you, but tell the woman those dolls are in the basement.”)

The smirking Italian girl, Lagonnis, Kay, with the fascinating under lip. The high school insolent.

The toy world within the commercial prison. The captured dream. The fluttering bird. The child enslaved. (And oh, the plodding tedium of those who serve this puppet-stringed doll of a toy department!) The mannequin bewitched, driven insane! The dream enslaved. And the corrupt toys, cheap, gaudy, desperately

N.B. (Marseille – 26 Juillet – 1949) Concerning the ambiguities, one can always be brilliant, and leave much to be debated. This is the exciting truth of life. Then, of course, the logical, realistic writer may explain everything – every thing with which he chooses to deal. But this is merely superficial. Thus, in my bidding to be bought – the pressed excretions of the beautiful dream of childhood. Only parts of it fool the child. The child knows. I saw no delighted child while I was there. There should be penny candies distributed.

(ed. note: Comment PH upon rereading her NB.)

The weariness! The eternal betrayal of the young! Childhood, captured, imprisoned behind a price tag. Behind the square counter that disperses inferior watercolor and clay modeling sets for the budding artists, the middle aged clerk stands rests one aching foot and then the other, and her face is tortured.

The ”days off” militate in Bloomingdale‘s favor: There is no time for a 48 hour vacation, a change of

scene. There is time only to sleep.

[The heroine will be a straight but at first a feeble thinker, not till the last able to act. Courage is what she needs, what she has not until the purge of the mother satiation. She aspires to decorate for the ballet, for the stage, her only reality now. The monotony of her view relieved by frequent excursions into the other (worldlier) characters, who will also be tinged with her extremism and clear child‘s view in their portrayal. End on hope, adulthood, freedom, happiness of maturity.] 2/6/49

(ed. note: Comment PH upon rereading her NB.)

___________________________________

Editor’s notes made by Anna von Planta, Highsmith’s primary editor since the 1980s.

___________________________________