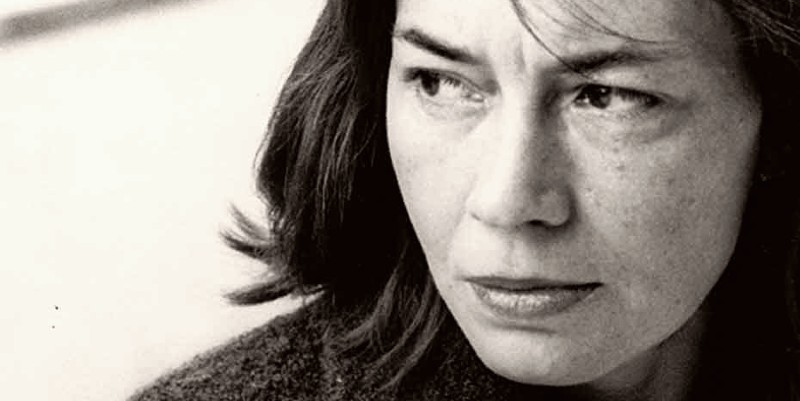

In June 1943, Patricia Highsmith tagged along with a friend on a social call to the Greenwich Village apartment of Stanley Edgar Hyman and his wife, Shirley Jackson. Highsmith’s interest was mostly in Hyman, whose employer,

the New Yorker, had a frustrating habit of rejecting her story submissions, but the brief description of the event she recorded later in her diary focuses instead on her conversation with his wife. Highsmith, just twenty-two years old, was struggling to make ends meet by writing for comic book publishers, whereas the twenty-six-year-old Jackson had already placed several short stories in respected publications. And so while Highsmith found Hyman to

be “horrible,” she grudgingly admitted that Jackson was “alright.” (1)

As the two drank coffee together, Highsmith reportedly told Jackson about her own work, and the more seasoned writer apparently gave the newbie much-appreciated advice about acquiring an agent (Patricia 239). This otherwise uneventful meeting warrants a mention in Joan Schenkar’s 2009 biography of Highsmith because, though these writers have rarely been directly compared to one another, upon further consideration the similarity between their work is strikingly obvious. Schenkar notes as a primary point of connection Jackson’s interest in “the same psychological states which obsessed Pat” (242), but the professional parallels between these women extend much further. Both explored a relatively cohesive set of themes in a wide variety of literary forms ranging from children’s books to science fiction to mysteries. And despite their reputations as masters of suspense, both also had cantankerous and sometimes decidedly unfeminine personalities (at least by midcentury America’s standards) that added an underlying, often subversive sense of humor to their writing. Each produced a body of work that has been described both as outside of time and of its time, and their literary legacies were neglected until relatively recently when, with the rise of feminist criticism and queer studies, each experienced a renaissance. For scholars today, then, this encounter is more than just a trivial anecdote of literary history.

The meeting of two great female creative minds so early in their respective careers suggests the tantalizing possibility of a very different narrative of post-war American literature, one that foregrounds the contributions of female writers and emphasizes a network of personal and professional connections between them. By studying these authors alongside Leigh Brackett, another midcentury, multi-genre writer whose legacy has been neglected, I hope to demonstrate the significant influence of women writers in the postwar era. In addition to highlighting gender influences, I will emphasize the way assumptions about genre—another important category of meaning—shaped critical perceptions of postwar publishing and its writers, thereby making the biases

of this era visible.

Though there are a number of significant similarities between these authors’ literary interests, most important for this study is the fact that all three took a fluid and creative approach to genre writing. Jackson’s distinctive fusion of various formats was her greatest strength but also a liability within an industry that preferred clear, simple (or simplistic) marketing narratives. Conversely, Highsmith was snared in just one of those categories—that of crime or suspense writer—and was never able to escape the burdens of such a designation. Brackett was perhaps most disadvantaged by genre biases, as she was a master of the pulpiest forms of two marginally respected genres: crime and science fiction. Yet all three writers, in part because of these associations, have been assessed mostly in comparison to male genre writers. For example, Jackson’s gothic approach has been considered against that of predecessors like Henry James’s Turn of the Screw (2); Highsmith is frequently grouped with Jim Thompson as crime writers who defied the genre norms of their era and thus influenced many authors to come; and Leigh Brackett is compared to Black Mask crime writers, usually Raymond Chandler, or, for her science fiction, her husband Edmond Hamilton or her protégé Ray Bradbury. Consequently, grouping these women writers upends narratives of literary influence and highlights more subtle elements of their treatment of gender—especially for Highsmith and Brackett, who were writing primarily in masculinized genres. Importantly, Brackett’s and Highsmith’s strong genre associations may have also disadvantaged them in another way. As feminist critics have sought to rewrite literary history, female writers whose work seems to hew more closely to the often-misogynist standards of their time period and genres were mostly left out of this process of reclamation.

___________________________________

Excerpted from On Edge: Genre and Genre in the Work of Shirley Jackson, Patricia Highsmith, and Leigh Brackett, by Ashley Lawson

(The University of Ohio Press)

___________________________________

Because Highsmith and Brackett utilized male protagonists (as did most crime and science fiction writers during this era), feminist critics have been too quick to assume their work adheres to a misogynist status quo. Instead, by foregrounding the influence of genre I will argue that both authors were aware of these conventions but sought to bend that framework to fit a more subversive purpose, one that focused on the way contemporary society—whether represented by a suburban small town or an intergalactic space colony—promoted restrictive gender roles that were often harmful to both sexes.

Taking a broader, more inclusive view of literary production during the postwar era—one that includes more than just the realist fiction written by white, mostly straight men—a new picture is revealed that adds depth and breadth to the version of this history as it is traditionally described in scholarship and textbooks. Beyond the holy Updike/Bellow/Salinger trinity (which may alternately include Miller/Williams/Cheever/Lowell) and their counter- cultural Beat Generation counterparts Kerouac/Ginsberg/Burroughs exists a wide range of writing neglected by the literary surveys that seek to define the major trends of this century. (3)

Those who seek to expand this view struggle to advocate for the worth of writers who do not meet the rather narrow qualifications of merit as they have been traditionally applied. Such criteria reinforce assumptions about the self-evident worth of these writers and make it difficult to add anyone new to the list, even as we become more aware of the biases embedded in our methods—especially those, I argue, of gender and genre.

Even fifty years of recovery efforts by feminist critics (the first generation of whom came of age during this period) has done little to shift the image of postwar literature as an era defined by male authors and the verisimilar or realist novel. Only recently with the growing critical prominence of authors like Jackson and Highsmith have we begun to accept a different version. With almost two centuries of the American literary tradition laid out before them, the woman writers of the postwar era learned to cope with gender stereotyping in a variety of ways, as evidenced by this trio. Each was shaped in relation to the conditions of the literary marketplace, whether she worked with or against it. Jackson continually faced both sexism and genre bias in periodical and book publishing, but she rarely bent her work to editors’ or critics’ tastes.

Highsmith typically preferred to write from a male point of view, but she never was able to shake the genre label that she felt disadvantaged her with American publishers and affected her sales in her home country. In contrast, Brackett fully embraced genre publishing and worked hard to excel at generic forms and thus achieve parity with male writers. Yet by grouping these three very different writers together, we can illuminate new patterns of women’s writing at midcentury that have been previously obscured. Specifically, each of these authors developed a distinctive suspense-forward style that playfully merged elements from multiple genres, a technique that was meant to reflect a growing sense that the world was more dangerous than even the pervasive Cold War hysteria of this time reflected, though in ways that the more explicit political propaganda ignored. They merged the dominant mode of literary realism with elements of genre writing to respond to the big questions of their era with startling and unnerving answers that inevitably produced even more queries and that perfectly illustrated the tension that defined the Age of Anxiety.

In addition to their genre connections, other striking similarities within this trio’s biographies encourage fruitful comparisons: all three women were born within six years of each other (between 1915 and 1921) and grew up in middle-class or upper-middle-class homes. (Jackson and Brackett were raised in California, and Highsmith lived between Texas and New York City.) They all had access to the kind of quality education that was becoming increasingly available to women (Jackson attended University of Rochester and Syracuse University; Highsmith graduated from Barnard College) and a certain degree of family support (though Brackett was forced to skip college due to a lack of funds, her grandfather offered financial assistance while she tried to become a professional writer). Brackett and Jackson both married fellow writers (Jackson married literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman, and Brackett wed fellow sci-fi writer Edmond Hamilton), and each was arguably even more successful

than her surprisingly supportive partner.

All three of these writers also chose authorship as a vocation from a young age, and they pursued their desired professional career with dogged determination. Brackett began writing at age nine by imagining sequels to her favorite films but began her “serious” work at thirteen (qtd. in Silver and Ward). She sold her first story to the pulp magazine Astounding Science Fiction while in her mid-twenties. Both Jackson and Highsmith achieved their first publications in mainstream periodicals during tweenhood: Jackson wrote a poem called “The Pine Tree” that won a contest in Junior Home Magazine when she was only twelve years old (Franklin 33), and Highsmith’s letters to her parents from summer camp were published in Women’s World magazine at the same age (A. Wilson 44). Jackson and Highsmith became stars of their college literary magazines, publishing stories that would serve as the foundation of their more mature work, but each struggled after graduation to get a foot in the door of the thriving periodical industry of the period. Despite some successes, neither could place their sui generis work in the slicks, even long after the success of their early books raised their respective profiles, and thus they often resorted to publication in genre magazines. In contrast, Brackett focused mainly on these specialized periodicals, especially pulp magazines. Brackett was one of the few women publishing in the male-dominated crime and sci-fi industries, and her gender ambiguous name likely mitigated discrimination to some degree until she became better known, though she usually claimed she never personally experienced any significant sex-based prejudice. And while there were many successful female crime and mystery writers during this era, few made use of the hard-boiled style that Brackett and Highsmith adapted to their own ends.

The most significant challenge when comparing this particular trio is the varying degrees to which each of these writers has already been reclaimed by the critical establishment. Jackson is now, finally, a well-established brand: all her writing for adults is in print, and two volumes of uncollected work have been released. Two biographies devoted to the author have been published, and a volume of her letters came out in 2021. Highsmith has been subject to similar popular interest. Three biographies have been written about her life, her novels were reissued by W. W. Norton in the 1990s, and the recent publication of excerpts from her diaries and notebooks, as well as a documentary about her life, has confirmed her status as a cultural icon. She has also been claimed as a major, if problematic, figure of LGBTQ+ history. Such interest, though, tends to focus more on Highsmith’s personality than on her writing.

Too often, the critical consensus agrees that she produced half a dozen masterful books, a bunch of middling ones, and a few clunkers, and so she is regarded as good for a crime writer. These latent biases are also found in literary scholarship. Most analysis of her writing treats it within genre studies of crime writing or as queer literature. Though Highsmith’s body of work does offer a distinct spin on both categories, such an approach limits her to the also-ran status that plagues so many genre writers. She is rarely studied alongside authors outside of the crime genre, and her broader literary influence has been mostly ignored.

Leigh Brackett is by far the least known of this trio, at least in literary circles. Among Star Wars fans, she is known as the writer of the first draft of the screenplay for The Empire Strikes Back, and sci-fi enthusiasts know her as an important foremother—the queen of the space opera—though most of her work is no longer in print. But recognition of Brackett beyond her prominence as a writer of crime and science fiction—not to mention as a screenwriter of classic genre films—has been limited, likely due to her mastery of such conventions. Of these three writers, she was the most faithful to genre expectations and worked almost exclusively with the publishers in the booming midcentury industries of both the crime and sci-fi fields. This may explain why her name is now the least known of the three. The fact that Brackett chose to live in both Los Angeles and rural Ohio further detached her from the monolith that was the postwar New York literary industry. Yet she offers important contributions to this study, because even her most genre-faithful work is playful and creative in both its use of the standard conventions as well as her incorporation of tropes and techniques from other categories of literary texts. Her treatment of gender is also more nuanced than has traditionally been acknowledged in the limited critical engagement with her work.

Another important commonality between all three of these women was, of course, their race. All three were white, which gave them a privileged point of view within the Jim Crow era of America’s history. Tracy Floreani has noted how, in a postwar period during which “ethnicity itself was being thought about in new ways,” writers from racial and ethnic minorities were emerging in greater numbers in the literary marketplace and doing important work to reshape concepts of national identity that had long been built on the ideals of white supremacy. As white women, these writers also worked from a distinct racial subject position, though one that has mostly been neglected in consideration of their work, in part because their engagement with issues of race was less explicit. Though Jackson focused almost exclusively on white female protagonists, she was the most interested of the three in addressing racial themes, especially in her short stories. The gendered anxiety that her female characters feel is often rooted in the same sense of threat implicit in racial hierarchies of the time. Though the segregationist philosophies (whether based in formal governmental segregation or more informal and often voluntary social divisions) were often justified as a means to protect this group of women, Jackson shows how the encoded ideology of racial difference only exacerbated that same sense of threat. While Brackett’s crime fiction sometimes included the kind of racial stereotyping that was typical of the genre at the time, she was more likely to address issues of discrimination in her science fiction writing, whether overtly or through the metaphors of otherness that were central to the genre, and both her sci-fi and her Western works emphasized the rights of Indigenous peoples. In contrast, Highsmith notoriously and belligerently held onto many of the prejudices instilled during her Southern childhood, and she became increasingly racist and bigoted in her beliefs as she aged. Yet her treatment of/obsession with the hegemonic white male of the period should be regarded as offering its own significant reflections on the nature of racial privilege in midcentury America. Thus, while race rarely constitutes the main subject of these writers’ work and while racial discrimination was not one of the challenges they faced when engaging with the literary marketplace, maintaining a focus on the less visible ways that race influenced their depictions of sociocultural dynamics is necessary in order to keep their own privileges visible. Just as this era of literary history has often been written as a masculine one, highlighting the racial homogeneity that is so often a part of this narrative offers another way to add depth to this important counterhistory of postwar American literature.

___________________________________

(1) Schenkar suggests a handful of reasons that Highsmith may have reacted so strongly to Hyman, but the most likely seems to be her strong lifelong antisemitic streak. Though this part of Highsmith’s entry was excised from the published version of her diary, the biographer reports that she called Hyman “the Jew” and deemed him “disgusting” (qtd. in Schenkar 242).

(2) Of the three, Jackson’s work, with its focus on female protagonists, is most likely to be considered alongside other female authors, though usually ones from earlier eras, including Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

(3) One useful indicator of canonization is, of course, textbooks. In the current tenth edition of the Norton Anthology of American Literature, seven female writers are included for the postwar era, as compared to fourteen male authors. The beneficial effects of critical revision are also evident in this edition, as the modernist period, which has been subject to extensive feminist intervention, boasts the fiction and poetry of fifteen women alongside twenty-three men. Additionally, the modernist section includes coverage of popular fiction, which allows for the inclusion of three more women writers, whereas the postwar volume has no such insert.