When I was six, I wrote a story called “An Adventure of the Past.” A fast-paced thriller (written in multiple colors), the story goes like this: a knight tries to save a lady accused of witchcraft, is given four days to prove her innocence, instantly falls in love and proposes, she says yes, they get arrested for witchcraft and burned at the stake, and their ashes live happily ever after. Whew.

It’s the closest I ever got to a happy ending.

All the stories I wrote as a kid were quite dreadful and sad. There was one about a bunch of animal friends trying to find the sea. A lot of them curled up and died along the way. There was another about a wistful girl who was actually a witch. If I remember correctly, she ended up in the ocean, turned into some mindless plant. The first novel I ever wrote (over a hundred handwritten pages, in cursive) was about a boy living in an alley in WWII London, eating rats to survive and conversing with a homeless man called the Old One. The title was “Rattus Rattus,” and things did not end well. All my characters went missing, got transformed against their will, failed in their endeavors, perished, fell off cliffs, drowned—you name it, it happened to them.

When I look back, it makes sense that my inclinations went in this direction. I was growing up in an oppressive, terrifying situation, and it went on for years, relentlessly hammering away at my childhood, the halcyon respites of cease-fires inevitably ending, like waking up from a delicious dream to roaring, enveloping darkness. I’m talking about war—I grew up in Beirut in the 70s and 80s. There were other distressing things going on as well, which also contributed to the repeated exorcisms I performed through writing: the horror, the threat, the mystery, the crucible, the resolution. A resolution which was, in all ways, an escape: whether tumbling off a cliff or disappearing into a new life as ashes.

It may be too easy to draw that line between life and fiction; I don’t know. It seems accurate.

The thing that stands out to me the most is that all these early writings had magical elements, right from the start. There was no distinction between reality and fantasy: they were one and the same. I never set out to construct allegories: whether a drowning witch or a dying unicorn, they were all essentially me, their travails rooted in the violence that overshadowed and eventually infiltrated our lives. Through my stories, I saw what I could not bear to see, I comprehended what my mind could not safely hold.

I take special note of this because as I grew older, a wedge formed in my thinking and pushed reality and fantasy apart. I internalized the expectations around serious writing, coming to associate magical tales with childishness. Particularly in grad school, I fell under immense pressure to stick to ‘literary’ writing and steer clear of ‘genre.’ I confess, I became a bit snobbish, scoffing at fantasy and sci fi and mystery, floating smugly on my ultra-literary cloud. But who was I kidding? My own thesis about growing up during the war (which became my first novel, The Bullet Collection) features a winged horse called Saisaban, who flies in and out of the story right to the very last page. A literary symbol, or the magic that sustained me through childhood, patiently circling, watching over me?

I’ve written countless stories and books over the years, some published, others unfinished or scrapped. It’s taken all this time, all that writing, to break that wedge into pieces and sweep it away. I kept swinging back and forth between ‘literary’ and ‘genre,’ struggling to find my true writing place. In one particularly grueling cycle, I worked on a fantasy epic for nine years only to see it rejected, whereupon I beat a retreat back to ‘literary’ writing, only to see that new novel get rejected, too.

I suppose I could have revised it. Instead, I pulled out the shredder and shredded the damn thing. Then I made stuff out of the shreds and became a book artist for five years.

Which meant, actually, a return to fantasy. One of the earliest pieces I made is a tunnel book showing an insomniac girl traveling through a ghostly palace and disappearing over a distant hill. Another is a miniature diorama of a girl trapped in a tower by a demon, the story of her plight in puzzle pieces. Her only way out is the window, far above the rocky coastline.

It’s astonishing to recognize I’ve been performing the same exorcisms for all this time, no matter the medium: the horror and mystery shaped by words or paper, escape the only resolution.

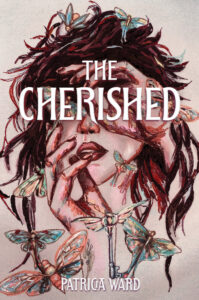

My new novel, The Cherished, falls into the same pattern. It’s YA because it just worked out that way, but it also makes profound sense that at last I should come full circle back to the writings of my youth, in which a young girl is confronted with something dreadful.

As in my childhood stories, sixteen-year-old Jo Lavoie’s daily existence is a torment, and she yearns for escape. On the surface, she seems to have a privileged, carefree life in a well-to-do family. Churning beneath this façade are terrifying half-memories and recurring nightmares about traumatic events to do with her beloved father, who is now dead. She’s further isolated by the casual mockery and disrespect the rest of her family shows him, and her by extension. She feels like she doesn’t belong in her own home. So, when she finds out she’s inherited the Vermont farm where her dad grew up, she leaps at the notion of a place she can call her own.

The story unfurls like a film in my mind, with a kind of hypnotic tension that builds and builds towards the gruesome truth of Jo’s inheritance. Jo freely departs from the bright, orderly, albeit constrained spaces of her present life and heads towards the frightening mystery of her nightmares. Door after door creaks open, leading her ever deeper into the past, her memories bleeding up through the muck of time, until at last . . .

It’s another exorcism, but I’m older now, and when I see sunlight on a field, I don’t feel empty. My girl won’t be going off any old cliff.

So many books, so many stories come to this, and how can I not marvel at this magical life? Jo Lavoie holds out her hand to my childhood self, who also peered into darkness, not knowing if she’d make it back. The Cherished is no ordinary escape. It’s a slow-burn delve into the self’s capacity to hold up in the face of horror and grief, and to find a way to exist in this world.

***