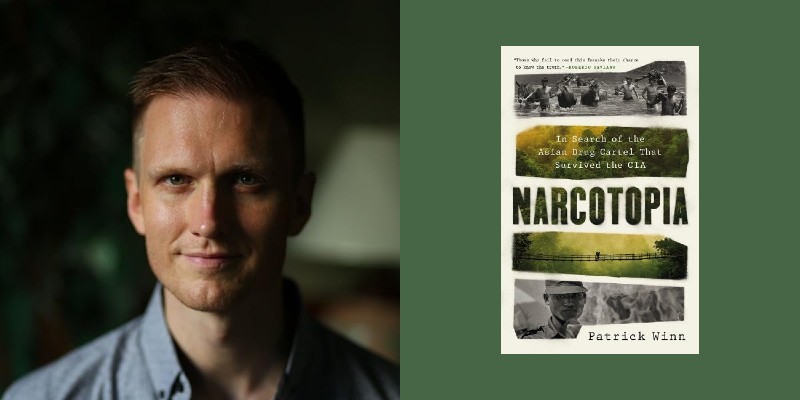

Patrick Winn’s Narcotopia: In Search of the Asian Drug Cartel that Survived the CIA tells an epic story that almost nobody knows. An American reporter living in Southeast Asia, Winn introduces readers to Wa State, which has spent a half-century building a thriving economy centered on heroin and methamphetamine. Wa State is in Myanmar, but with a population of 600,000 and an authoritarian regime that collects taxes, operates schools and polices its borders, it’s essentially independent.

There are lots of lurid tales about the Wa, who once made a practice of beheading intruders. But the book’s bigger story involves America’s hapless war on drugs. Winn spent several years interviewing Wa citizens, U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency lifers and CIA spies. He learned that Wa-produced heroin found its way to American soldiers in Vietnam, and in the years that followed, CIA-linked opportunists helped the Wa become a force in Southeast Asia’s meth trade.

Speaking from his home in Thailand, Winn explained why so few Westerners know of the Wa, how Wa State’s traffickers seamlessly responded to an economic boom in Asia, and why, as he writes, “an honest telling of the Wa story” undermines America’s “national myths.”

How do you describe Wa State to readers who’ve never heard of it?

Wa State is one of the most fascinating places in the world. It’s a fully functioning country that’s on the map, but it’s not delineated as a proper country, it’s not recognized by the United Nations. The Wa don’t seem to care whether the rest of the world sees them as a nation, but in every respect, it is. They have borders that are very well-defined—if you go into their area and you haven’t been invited, they will eject you, by force if necessary. They have their own national anthem, their own ministries of education, finance, health.

It’s easy to demonize the Wa for building an economy around heroin and, later, meth, but is it right to say that geography played a big role?

This soil is really bad. It’s a very violently sculpted part of the world—peaks and valleys and slopes everywhere. Even back to antiquity, the Wa struggled with growing enough food. The opium poppy was, in a way, a godsend because it grew really well on the slopes, and it transports well. You can take a kilo of opium and pack it up tightly in canvas, and you can keep it for a year or two. The opium poppy gave them an economy.

This all began 50 years ago, or more, you explain in the book.

The Wa were very adept at moving opium to heroin refineries in Southeast Asia, and then moving that heroin in shrink-wrapped kilo bricks throughout the world. One destination was the United States. Somebody in the ‘70s, ‘80s, ‘90s trying to make money off drug trafficking is going to hit a ceiling pretty fast in Southeast Asia, because most people there in those decades didn’t have enough money.

In the past 25 years, the emphasis has been on selling methamphetamine regionally. That’s because Asia came into its own as a booming economy. Now you don’t need to ship narcotics all the way to the United States. And heroin is really not in vogue in this part of the world. Methamphetamine is a go, go, go type of drug. It can sustain you if you’re working in a factory, driving a taxi, doing construction work—all these labor-intensive jobs that you’ll find in a growing economy.

You make a point of saying that your book isn’t told from the perspective of American spies and law-enforcement agencies. Why was that important?

I was born in 1981. This was very much the “war on drugs” era. The propaganda was heavy—Nancy Reagan saying there’s no moral middle ground in this crusade. That always seemed fishy to me. I’m really fascinated by good vs. evil narratives. Because I think that they’re mostly bunk. The Wa people have been targeted in a way that’s entirely invisible to the American public.

You’re right, Americans know nothing about the Wa—myself included before I read this book. Why is that?

The Wa don’t seek attention. Even the Taliban has a foreign-affairs department that will speak to American reporters. Hamas has a public affairs team, as I understand it. The Wa are so widely disparaged that they’ve given up on that.

For its part, the DEA, which always talked up its efforts in Latin America, never said much publicly about the Wa.

The strategy of the DEA has always been to build up someone before they take them down. So if you find out that the DEA has arrested Joe Bananas, your first question is going to be who the hell is Joe Bananas? But if they spent five years telling you how Joe Bananas is at the center of the drug trade and then they catch him, it’s headline news. The Wa drug trafficker-in-chief is Wei Xuegang, but they’ve never really come close to catching him.

And that’s why they haven’t built him up—because they’ll never get him?

That’s exactly right. There were efforts to build him up when they thought they might be able to catch him 25 years ago. But you won’t hear them talk about him at all now.

Another reason the Wa are notorious is their history of head-hunting. They used to decapitate enemies.

I’ve tried to understand the logic behind it. There’s logic behind French revolutionaries cutting people’s heads off. There’s logic behind Scottish clans doing it. There was a cruel logic behind U.S. soldiers doing it in the Philippines during the US-Philippine War. It’s very effective at shocking your rivals. For the Wa, displaying human skulls on sticks scared clans they were beefing with, British colonial explorers, and the Chinese dynasty next door. It kept people out of their territory.

The other reason they did it was a belief that inside every human head exists a spiritual force. Their need at the time was to grow crops, and so it was believed that by scattering the flesh from someone’s face and head around their crops, it was a sort of dark force that would scare away any threat to their crops.

When did this stop happening?

I think the very latest that you would have had head-hunting would be the early 1970s. It would have been on the wane for a while, but up through the ‘50s it was still happening in a serious way.

You detail a long clash in Southeast Asia between the CIA and the DEA. What resulted from this?

In the course of writing this book, it became very obvious that this was another example of the CIA utterly failing to comprehend the repercussions of its actions. The CIA used drug traffickers as intelligence-gathering assets during the Cold War in Southeast Asia, and my research indicates it protected them from prosecution from local governments—and when the DEA came into the picture initially, from the DEA as well. The CIA and the DEA just think completely differently on this issue. If the ultimate goal of the CIA is to maintain American supremacy and working with a drug trafficker will weaken your rival or help you get intelligence on your rival, they think it’s worth it.

Whereas the DEA wants to shut it down completely, no matter what.

The DEA sees this from a strict law enforcement perspective—our job is to take down drug traffickers, whoever they are. The law is the law. And as a former CIA officer that I interviewed for this book explained to me: We’re allowed to break the law. And then he quickly followed up, Foreign laws, not US laws. But… (laughs). Look, spies deceive. Spies lie.

When there’s a drug-trafficking organization out there that is not serving America’s interests or has no valuable role in intelligence-gathering, the CIA is happy to help bring them down. The CIA has an anti-narcotics division, and I’m sure it’s responsible for bringing hell on all sorts of drug-trafficking syndicates. But not the ones that are valuable to maintaining American dominance.

What’s the relationship between enabling drug trafficking and the heroin that American soldiers discovered during the Vietnam War?

The roots of the war on drugs originate in Southeast Asia. The moral panic over narcotics really began with GIs in Vietnam doing heroin and bringing that addiction back home to the United States. The war on drugs was a response to that. The heroin that those GIs were doing originates in the highlands of Southeast Asia, and one of the major producers of the opium that was refined into heroin were the Wa people. That opium was collected by an organization affiliated with the CIA, used by the CIA as intelligence-gathering assets.

Today, Myanmar is in the midst of upheaval. What does this mean for Wa State?

Myanmar is undergoing a raging civil war in which much of the population has risen up against this awful military junta that’s ruled the country for decades. Whatever the outcome, the Wa will be OK. They’re headquartered on the border with China. They can receive fuel, food, technical assistance, trade over the Chinese border. I feel very confident in predicting that whoever wins will go to the Wa government and say, As you were, we don’t want any trouble.