“To be like the rock that the waves keep crashing over. It stands unmoved and the raging of the sea falls still around it.”

–Marcus Aurelius

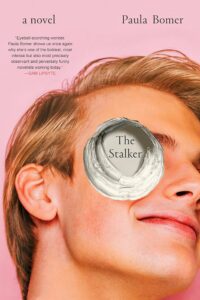

When I first started writing The Stalker, I didn’t know how dark or violent I wanted it to be. I knew I wanted it to be mean and funny, but to my great delight and horror, the narrative moved me to follow a path to some serious destruction. I knew that Robert “Doughty” Savile would be a liar. I knew he was going to be a piece of garbage person. But I didn’t see the middle, or the end, until I got closer to it. This is the great joy of writing, being pulled in a direction that surprises you. But I’ll be honest. I upset myself. For some time, in the first draft, I thought I would make him be the actual devil. I’m not entirely sure if that desire for him to embody Satan ever left the narrative completely.

I have always read a lot of crime and noir fiction. Jim Thompson—I have an aborted Jim Thompson-esque novel called Mussel—was a great joy of mine throughout my twenties and thirties. The tight quick narratives, the downward spiral of horrific events, the lies and manipulations, the desperation, the otherworldliness cemented in dark reality. My favorite novel of his is A Swell Looking Babe, where Thompson’s Freudian weirdness shines brightly. I love Nathanael West, James Ellroy, Flannery O’Connor, Joyce Carol Oates, in particular the short story “Upon The Sweeping Flood.” The short perfect novel, The Fifth Child, by Doris Lessing.

One of my favorite moments in my writing life was when Minna Proctor reviewed Baby and Other Stories in Bookforum and compared my writing to Patricia Highsmith’s. I think of her as a huge influence on my work. I was so honored and felt so well seen. From that collection, in the story “Breasts” which originally appeared in a Noir Issue of The Mississippi Review, a naive young woman is manipulated into a violent robbery of the The Mars Bar in the East Village of New York City. Another story, “A Galloping Infection,” involves the slow death of a young mother, seen from the vantage point of her indifferent husband. And lastly, the center of the story “She Was Everything to Him” is a vicious act of marital rape.

During one of the strange wormholes I went down when trying to figure out how to write The Stalker, I dug up a chapter of Creation Myths by the Jungian scholar Marie-Louise Von Franz. The title delighted me: “The First Victim.” The argument is that all creation myths are based on violence and victim sacrifice. It always cracks me up that religions are associated with peace, particularly the Western new age practitioners’ fascination with Eastern religions. Von Franz writes, “the Taoist philosophers, who are so fully aware of the questionableness of human consciousness, have therefore quite rightly stressed creation as a sort of murder, the murder of a kind and innocent being.”

From here, one would ask, but why? Why would someone murder a kind and innocent being? My answer came from a man I once trusted who then later showed his true self, sadly on my behalf, not for the first time: because they can.

Men hurt women because they can. If we want to invoke some science into it, now that we covered religion, the brains of many men shoot out a bunch of dopamine when they hurt women. For instance, our government. There is no need, there is no anguish, there is no end result to obtain, they just enjoy it. But I would argue that beyond the fact that they can, or that they enjoy it, they also feel entitled to it.

Crime is an understandable obsession. We want to hear, read or watch the stories of crimes so that we can feel less alone, feel understood, or if we are young, feel lucky that we haven’t experienced anything so atrocious. It helps us understand our victimhood, the bullies from our childhood, the cruel treatment at the hands of others throughout our short lifespans on our dying planet. Crime is essential to the human experience. And those who can, and those who feel entitled to do so, commit them.

The Stalker starts out in an exclusive, historically white, wealthy suburb of New York City. I went to a boarding school near there. I constantly was put in my place in obvious ways. “Indiana, have we conquered that yet?” That phrase was weirdly said to me by different boys and later men throughout a large chunk of my lifespan. It was also clear that I was expected to clean up after, or serve in some other capacity, the “wealthier” people in my social circle during my adolescence and young adulthood. This was most often demanded of me just by the entitled staring ahead, and doing nothing. Just nothing.

Once I landed on Doughty’s inner voice, I moved quickly to having his M.O. be Doing Nothing. The great power of just being there. Being still. In The Art of War, of which many a CEO has a tattered copy under his pillow, Sun Tzu says “be still as the Mountain.” This tactic is wildly underrated in the war men create in so many domestic situations. They are there. They are in your house, in your apartment. “Weaponized incompetence” is a form of this reality. Like many writers, I rely heavily on my early readers and the author Julian Tepper said to me about Doughty, “he stays the same, but everything around him changes.” Why is that so? How can so much damage be done by doing nothing?

Make no mistake, before a man sits on your couch doing nothing, he has other plans. He waits patiently for his moment. Part of stillness also is silence. Silence is a huge weapon in the home. One thing that bothers me most about the reality of male violence against women is how it’s so often couched in terms of spontaneity, or worse, a misunderstanding. So often in the excuses by any accused man is that it “just happened”. Violent crimes are often thought of as either “pre-meditated” or not. And the ones that are not are seen as more forgivable. I don’t really believe in crimes of passion, but if they do exist, they are the rarer kind.

With Doughty, and with most difficult, painful subject matter, humor is my way through the banal horror of the great pleasure he gets in making every relationship in his life transactional. His only interest in people lies in what he can get out of them. He literally cares about no one. This person lives in a tent, she’s trash, I can do anything to her. This person has an apartment I like, I will stay there. This person can give me beer. It’s all math to him. When he sees a person, he might notice their hair or shoes, but really, it all becomes part of the math. What can they do for me? What can I extract from her? Money? Sex? Social connections? A free flight to Vegas?

Is The Stalker a cautionary tale? I think it’s too late for that. It’s a story of our time and a story as old as the ancient philosophers and clergy who didn’t believe women were actually human. The banality of sociopathy is that men often reap pleasure in violence, that maybe when Jane’s Addiction sang “Sex Is Violent” they weren’t just accidentally quoting the radical feminist Andrea Dworkin (whose works have recently been reissued by Picador) but sang the truth of far too many women born on this planet. Is feminism, like history, one step forward, two steps back? No. My mother couldn’t open a bank account on her own when she had me. It was legal to rape your wife in most parts of the United States until 1993, when I was twenty-five. What to do? Smash the patriarchy. All bullies are cowards, garden variety sociopaths are not uncommon, no matter if they wear a tie and have a huge bank account, coach high school basketball, are the best accountant in town, teach math, or groom your dog. You cannot know, until you do.

***