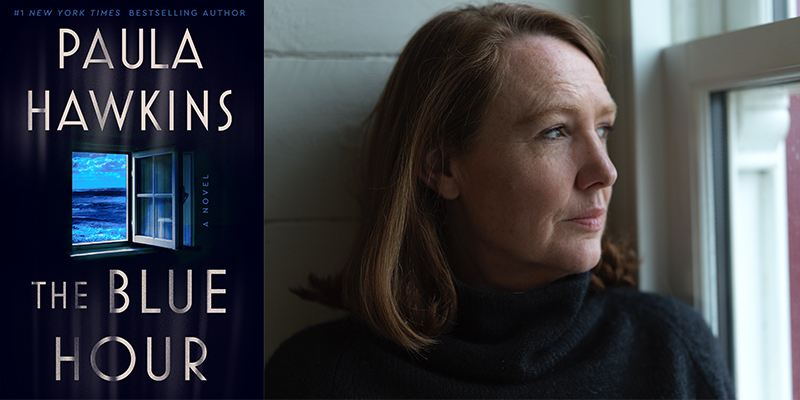

With The Blue Hour, Paula Hawkins delivers a different kind of thrill than the propulsive The Girl on the Train which put her on the map as a bestselling author. This new novel, a dark deep dive into obsession, betrayal, and the artistic life compels no less but feels more sophisticated — a slow burn that satisfies both the thrill-seeking and the cerebral.

Deeply atmospheric, The Blue Hour centers around Eris Island, an isolated Scottish island only accessible from the mainland when the tide is low. Renowned artist Vanessa Chapman, seeking solitude, makes the island her home and muse. Years later, the discovery of a human bone in one of her sculptures brings into question not only her legacy but the fate of her ex-husband who mysteriously disappeared two decades before. James Decker, a young curator long obsessed with Chapman, ventures to Eris Island to collect the artist’s works and piece together some answers. But local doctor Grace, Chapman’s long-time companion and fierce protector, hinders his attempts to uncover the artist’s secrets.

In The Blue Hour, Hawkins tightly weaves plot and theme to create a claustrophobic tension akin to a barometric pressure drop ahead of a gathering storm. Then finally, thunder cracks in an inevitable and haunting finish.

I connected with the British author over Zoom for a lively and insightful conversation. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jenny Bartoy: I spent a weekend with my nose buried in this novel, absolutely riveted and ignoring all responsibilities. I’m curious about your inspiration for The Blue Hour.

Paula Hawkins: I tend to think about things for quite a long time before I write them, but the setting was a big part of where it came from. I’d been on holiday in France, on the coast of Brittany, and walking there, I remember seeing these little tidal islands and one had a single house on it. That struck me, and I felt that little prickle of an idea. What sort of person would want to go and live in a house on an island that’s inaccessible for half the day? There are obviously lots of good, crime-y possibilities with a place like that, lots of locked room possibilities. But I was thinking more about the kind of person who would want to go there. And I had been wanting to write about an artist. We have quite a romantic view of the lives of artists, but there’s lots of scope for conflict and questions around legacy. I think mostly it was this idea of what it is to be a woman working creatively, and this woman being drawn to this very lonely place where she can be completely free to live her life and create. But then, what are the possible downsides of that? What might go wrong?

JB: Early in the book, the artist at the center of the story, Vanessa Chapman, writes in her journal about this exact thing: “This freedom is intoxicating / I eat when I please / Work when I please / Come and go when I please / I answer to no one, only the tide.” It’s almost like a poem or a mini-manifesto. Her euphoria will likely feel relatable to many readers, particularly women. In this, The Blue Hour feels almost like a radical text in asserting Vanessa’s independence.

PH: It’s a kind of selfish impulse to do whatever she wants, but I think a lot of us can recognize that impulse and how amazing it would be to completely run away from it all and just focus on the thing that you love. To not have to answer to anyone, to not have anyone knocking on your door, not even notifications on your phone. That idea of being somewhere silent, somewhere remote, somewhere where you can be at peace and focus on whatever it is that you’ve wanted to devote your life to, it’s extremely tempting and seductive to me.

JB: Yes, freedom from expectations! Vanessa, to me, exemplifies what we might think of a traditional male artist: obsessive, unapologetic, mercurial, promiscuous. But unlike her male contemporaries, she’s portrayed negatively in the press. One of your characters, Helena, schools her husband on this, saying: “Disagreeable and prickly and strident — that’s just what people say about a woman who knows her own mind.” It’s refreshing to see this called out. Can you tell me more about your intent in underlining these inequities?

PH: [Vanessa] has a touch of the art monster about her. That’s all she’s interested in, and that’s what she wants to dedicate her life to, which, when men do it, we all go, “Oh, he’s a genius.” And then when women try to go in that direction, they are vilified. I’m thinking of people like Doris Lessing, for example, who kind of abandoned her children to go and write, and there’s literally nothing worse that she could do. I very much wanted to call out the way that women are written about, particularly in the 90s [when Vanessa is making art] — a lot of it was pretty grotesque, and actually a lot of the time women artists weren’t written about at all. [When they were], there was always a focus on what they looked like, and any woman who wasn’t pleasing all the time, who didn’t try to please the critic or the journalist, would have been told that they were aloof or difficult or what have you — just for having some boundaries or maybe not smiling enough. So I definitely wanted to underline that point. There is still an expectation on women in public life to be pleasing in a way that we don’t ask men to be pleasing. If a man is difficult or aloof, that’s fine, but for women, she’s being a bitch.

JB: This novel touches on violence against women and on the various ways in which women respond to violence and betrayal, particularly within the context of these sociocultural expectations. Vanessa is obsessed with the Italian artist Artemisia Gentileschi, and her painting of Judith beheading Holofernes. Can you speak about the theme of violence and the importance of this painting in The Blue Hour?

PH: Gentileschi is often written about in the context of being a victim of violence herself. She was raped. That’s often referred to when people discuss her painting, and I think that’s probably a little bit simplistic. What I loved about her version of Judith and Holofernes is these two women fighting together side by side. Often you see Judith with her servant just standing next to her while she does the beheading. But there’s a kind of equality between Judith and her maid. It’s about a man getting his head cut off, but it is an extraordinary painting, really visceral. And there was something about that sense of fighting back that I could see really appealing to Vanessa. I think probably most women have, at some point in their lives, imagined the thrill or the catharsis of responding to violence with violence in that way, even if you don’t actually want to do it. And it was something that then sort of runs through the book. I like to think that Vanessa, to some degree, could see the attraction of that response to violence.

JB: You kept your cast of characters concise, and at the center, you have these two women who are both powerful yet misunderstood in terms of the truth of who they are. Vanessa is this renowned but reclusive artist, and Grace is this local doctor quietly saving lives but feeling utterly lonely. Can you tell me more about how you developed these two characters?

PH: Character is something that I think about a lot. I very much do not want the characters to just be a type. And it’s quite easy to slip into those tropes, I think. But I tend to live with the characters for quite a long time. Vanessa is beautiful and reclusive, but what’s interesting about her is that you get to know her gradually through her diaries, and you see how she can be conflicted: quite unsure of herself, and yet very focused on her work. You can see how she’d be an attractive person to be around, but she’s not always very easy or necessarily kind. She’s one of those people who shine her light on you for a bit, then she goes cold and goes off on another thing. Grace was a bit tricky and took a while to develop. I was thinking about somebody who had disappointments early in life and somehow has not managed to deal with them. She never managed to deal with rejection properly; she tends to overreact to things; and I think sometimes, people like that become lonely. And their loneliness actually makes them repellent to people. It’s a horrible thing to say, but we tend to avoid lonely people, because nobody wants to be “infected” by the loneliness. And then you sort of think, what would that be like? She tries very hard, actually, and she has created this life for herself where she’s useful and she’s needed and she’s very much part of her community. So she isn’t just one thing or the other. Nobody’s just one thing or the other. We all have the capacity to go in all sorts of different directions depending on the circumstance.

JB: The Blue Hour is an incredibly atmospheric novel, with Eris Island at the center of it. This small island is only accessible when the tide is low. As such, it is both prison and freedom, heaven and hell. Can you tell me a little more about how this setting guided or enhanced your narrative?

PH: As I touched on, one of the things I had to imagine was the sort of person who would want to go there. It narrowed the cast down in quite a natural way. There’s not a lot of people [around Eris Island], so relationships are stripped back. Certainly with Grace, because of her loneliness, Vanessa is sort of the sole connection that she has, and you see every part of that relationship’s dynamic quite close up, in a way that you might not if they had a whole big group of friends and they were in the middle of a city. Vanessa has chosen to withdraw. But then you can tell from her letters to her friend Frances that she doesn’t always relish the solitude. Parts of it she absolutely loves, but then it does mean that she’s incredibly reliant on the few bits of social contact that she has, be it with Grace, or even when her ex-husband comes, she’s quite happy to see him. The other setting is Fairburn, this grand house. And that’s also a very narrow cast of characters, with difficult family relationships, and this love triangle as well. I do tend to do that deliberately, to try and strip things back, so that I can just focus quite narrowly on the particular relationship dynamics that I’m most interested in.

JB: You write: “How very odd it must be, living at the mercy of the tide.” You use the tide narratively to create constraint and tension, but also metaphorically. A certain ebb and flow is a natural part of life and narrative, but here the writing felt intentionally rhythmic to me and I wonder if the tidal theme played a part.

PH: I think partly, yes, that was intentional. You do want the tidalness to mean something, in addition to it providing all those time constraints which are good for a crime novel — because you can figure out that so and so couldn’t have been there at a certain time, and people are getting trapped, or whatever. But there is also this sense of having to surrender yourself a little bit and to accept that things ebb and flow. And that’s something which Grace is utterly incapable of doing, this accepting the ups and downs of life. She wants to sort of control where things are, whereas Vanessa is much more ready to do so. There’s a kind of power in surrendering yourself to accepting that you’re not going to be in control of everything.

JB: You write: “Vanessa painted what she loved, she painted her freedom, she painted the sea. She painted what she feared.” Do you think writing offers the same outlet or catharsis? Do you paint your freedom and your fears in your novels?

PH: Yeah, I think to some degree there is an element of that. [Writing] is sort of trying out lives that you might have lived, not literally, but imagining yourself into other places and what it would be like. I’m not sure that it’s very good therapy. You would probably do better paying someone and talking to them. But for a lot of people, [making art] feels essential in the same way that, if you like running or what have you, that comes to feel essential to your general peace of mind. For me, work has always been really good in that way. [Writing] helps me feel useful. And that is how you get through the day. That is how you express yourself. It certainly feels important to me.

JB: You refer to the author Daphne du Maurier several times in this novel. I know your work has been compared to hers, so these references throughout the novel feel a little meta.

PH: I was definitely thinking about du Maurier a lot. There’s a couple of the short stories that I’ve really liked. The Birds is the one that the film is based on, but the story is incredibly dark, darker than the movie [which now] looks slightly ridiculous because of the dated effects. This story feels quite prescient, because it seems to look towards the environment changing, towards climate changing, and something happening in the natural world that is very threatening and terrifying. So I was thinking about that more atmospherically than anything else. And the other story is Don’t Look Now, which people know from the Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie movie. There’s this whole sense in Don’t Look Now that the protagonist doesn’t see what is really threatening to him. He’s looking one way and not seeing the real danger. And that is definitely something that happens [in The Blue Hour], with [a main character] distracted by what’s going on in their home life, sort of looking one way and not seeing where the existential threat is. So I dropped in a bit about Don’t Look Now right at the beginning of the novel.

JB: Your first thriller, The Girl on the Train, became a global bestseller. I imagine this was as exciting as it was daunting when it came to crafting your next novels. How do you navigate expectations, both external and your own, when it comes to sitting at your desk and putting words to paper?

tiPH: I think I really rushed into the novel after The Girl on the Train. In fact, I’d started writing it before The Girl on the Train was published, but I should probably have taken my time a little bit more. I was desperate to be ambitious and do something different. Into the Water was this polyphonic novel, with lots of different orators. A lot of people didn’t think it worked. It is quite overwhelming to have a success like The Girl on the Train. I was touring all the time, and it was quite difficult — I actually needed to sit quietly at my desk and really think in order to get some decent writing done. So what I would say is, if you are under a lot of pressure for whatever reason, it’s really important to take your time to make sure that you’re writing the book you need to write now. I’ve got lots of ideas and I’ve got lots of people living in my head — it’s about choosing the right idea and which people actually belong in this story. Because you don’t want to throw away your good ideas or your good characters. You want them to fit into the right story. Make sure that you’re on a firm base before you start writing.

JB: That’s excellent advice. One last craft question. This novel, to me, felt written in brushstrokes, with the different points of view and Vanessa’s diary entries thoughtfully layered to paint an increasingly clear picture. Do you have any insights to share about your plotting process?

PH: For this novel, I sort of knew [the general plot] quite early on. Once I came up with this idea of the bone in the sculpture, that sort of showed me the way. That doesn’t always happen in books. In fact, it hasn’t happened in the last two but I think in both The Girl on the Train and in this novel, I could see the direction of travel quite clearly from the beginning, which is a great thing to have. Then the rest of the plot elements — that is actually just hard graft, making sure everything fits in exactly the right way. How you reveal certain bits of information and how you reveal them to the reader but also to different characters in the novel, so people know things at different times, is a big part of what creates suspense and tension. I don’t think there are shortcuts for that. Well, not for me. I just have to write myself into it and figure it out.

***