I always aim for authenticity in my mystery novels, especially when it comes to depicting law enforcement personnel and methods of investigation. There are a number of sources to help in this endeavor: Facebook groups likes “Cops and Writers,” police procedure manuals and guidelines that are easily found on the Internet, attending conferences that feature law enforcement panels, and chatting with my local police. Having those conversations with folks in law enforcement—getting a flavor for the vernacular, discussing the personal issues behind the badge, hearing firsthand the highs and lows of the profession—is, in my opinion, key to bringing depth and realism to my characters.

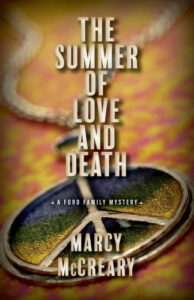

My latest novel, The Summer of Love and Death, is set in Monticello, NY, ten miles from Max Yasgur’s Farm, the site of the Woodstock Music & Art Fair. It’s a dual timeline narrative—1969 and 2019—whereby a present-day murder has all the earmarks of a 1969 serial killer case. And so I began to research how law enforcement operated at the 1969 Woodstock Festival. I found some information on the Web, but I really wanted to speak to someone from the NYPD who had actually volunteered for the infamous “Peace Force.” I was looking for behind-the-scenes anecdotes and firsthand experiences that I could possibly weave into my story.

Call it kismet, but the stars aligned in September 2022 at Bouchercon. At the bar in the Minneapolis Hilton, I chatted up Greg Renz (author of Beneath The Flames) about my work-in-progress at the time and my desire to find someone who worked law enforcement at Woodstock. Soon after returning home, I got an email from Greg introducing me to Nick Chiarkas, crime writer and ex-NYPD who volunteered for the Woodstock Peace Force. He became both my trusted resource and my inspiration for the Woodstock scenes depicted in the novel.

If you’re curious about how the volunteer-NYPD “Peace Force,” Wavy Gravy’s Hog Farmers’ “Please Force,” and the Sullivan County police departments managed to keep the peace at Woodstock, stick around for my interview with Nick Chiarkas . . .

Marcy: How did you get the “Peace Force” gig at Woodstock?

Nick: NYPD Commissioner Howard Leary originally agreed to provide NYPD cops for security at Woodstock. However, he was embarrassed by a front-page story in the New York Post that inferred NYPD would be working with Wavy Gravy’s Hog Farm employees and withdrew consent. Even after Woodstock’s head of security, Wes Pomeroy, spoke with the Commissioner and made it clear that Wavy’s group would only be helping with odd jobs as the “Please Force” and the NYPD would be the security at the festival and be known as the “Peace Force,” the Commissioner was still not willing to budge on his decision to pull out. But, he agreed to not take action against any off-duty NYPD cop that worked for Wes Pomeroy as security.

At the time, I was a cop in the 10th Pct. The clerical police officer there knew Wes Pomeroy and asked me and my partner if we would be interested. We simply had to complete a short application. My partner Tom Kenney (the best cop I ever knew) and I were chosen so we both took a few days off and joined Wes Pomeroy’s team of about 275 off-duty NYPD cops at Woodstock.

Marcy: What was your directive from Wes Pomeroy, the head of security?

Nick: You have to understand that we expected close to 100,000 people. Over 400,000 showed up. In the crowd were Hell’s Angels, the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, street gangs, hippie communes, and regular folks. With the unexpected crowd, Wes and concert promoter, Mike Lang, wisely decided there would be no gate to sell or collect tickets. Wes had only three rules for the attendees: 1. Don’t hurt anyone, 2. Don’t steal from anyone, and 3. If someone needs help, help them or call us. Everyone cheered. To us, he said, “You are here to help people, de-escalate issues, save lives, and do good. That’s it.” And that’s what we did. Break up fights, negotiate disputes, patched up cuts and bruises…and we talked with everyone, and anyone about anything—the Vietnam War, the draft, politics, religion, rich and poor, the Beatles weren’t coming, anything and everything, we just talked and listened. We helped to keep the peace and serve the needs of the attendees.

Marcy: Were there any conflicts among the Peace Force, Please Force, State and local police? Or was it all kumbaya?

Marcy: Did you take away any valuable lessons from your experience policing at Woodstock?

Nick: I learned the power of just talking with (not to or at) other people—even when you disagree, even when they are breaking the law. So much can be de-escalated if you calm down, breathe, and talk to people. Shortly after returning from Woodstock, Kenney and I were part of a line of cops at a student protest around NYU. Facing me in the crowd was a co-ed with a sign; she spit at me and called me a pig. Things got quiet around us. Kenney looked at me, laughed, and said, “We’re home; what do you wanna do?” I looked at the young woman. I could have arrested her, but instead, I said, “That hurt my feelings. You don’t even know me or what I believe, and yet you spit on me; we’re all just people.” I really said that. She broke down and kept apologizing as she wiped her spit off of me with a scarf. After our experience at Woodstock, Kenny and I talked more with residents and tourists in our sector (Sector A, 10th Pct.), and we solved problems, prevented issues, and improved our working situation.

Marcy: What was your most memorable experience at Woodstock?

Nick: My partner Kenney and I were often around and on the stage. At some point early Monday morning, Hendrix pointed at me and said, “Hop Town.” I didn’t know what he wanted, so I said, “What?” and walked toward him. I was wearing my short-sleeved red Peace shirt, and the bottom of my 101st Paratrooper tattoo was showing. He pointed at it and again said, “Hop Town.” Now I knew. Just about everyone at Fort Campbell who wanted a tattoo got them in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, otherwise known as Hop Town. That’s when I learned that Jimi Hendrix served as a member of the 101st Airborne Division a few years before I did. It was a good talk and, for me, memorable.

Marcy: I hope you don’t mind that I stole that Jimi Hendrix story for my Nick-inspired character, Sal Valero.

Nick: Not at all. I loved the character of Sal Valero; he is way cooler than I have ever been. So, thanks for the upgrade.

***