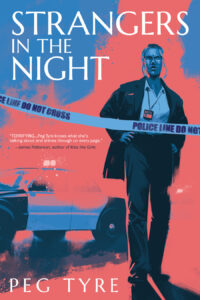

Peg Tyre and Peter Blauner are New York Times bestselling authors who have over a dozen published novels and multiple awards between them. They’ve also been married for 34 years. Their novels STRANGERS IN THE NIGHT and THE INTRUDER, originally published in the 90s, are both being released for the first time in hardcover by Dead Sky Publishing.

Peter Blauner: Most people these days mainly know you as a responsible and respectable journalist who writes very seriously about subjects like education. They have no idea you published a pair of funny, scary, sexy crime novels back in the 1990s. You want to tell them how that happened or should I spill the beans?

Peg Tyre: Well, getting a book republished after all these years is like meeting an old version of yourself. I guess I’ve evolved. The newspaper business I was part of went away, and other opportunities in journalism came up, and then other opportunities outside of journalism. I’m the same person, just older. What do you think, Peter more mellow?

PB: I don’t think people looking for “mellow” reach for the Peg Tyre shelf. I think people looking for excitement and scintillating ideas are more in your aisle. Anyway, when you wrote this book, you were already holding down a full-time job covering crime for a New York newspaper and raising a toddler. What on earth were you thinking?

PT: Ha! From one point of view, it was a kind of madness. From another, it was just the writing life. Nobody ever says, “Ok, now the world is gonna just slow down for you so you can figure out how to write that novel.” You have to do it however you can. One thing about living with you, Peter, is that your work habits are like a metronome. Very steady. Very deliberate. Very unswerving. I absorbed some of that, which I needed to be productive. I’ve always had a lot of energy and a weird stubborn kind of stamina and focus but watching you defend your regular writing time helped. I also felt like these stories were bursting out of me and it was a great relief to sit down and try to get them on the page.

PT: Ha! From one point of view, it was a kind of madness. From another, it was just the writing life. Nobody ever says, “Ok, now the world is gonna just slow down for you so you can figure out how to write that novel.” You have to do it however you can. One thing about living with you, Peter, is that your work habits are like a metronome. Very steady. Very deliberate. Very unswerving. I absorbed some of that, which I needed to be productive. I’ve always had a lot of energy and a weird stubborn kind of stamina and focus but watching you defend your regular writing time helped. I also felt like these stories were bursting out of me and it was a great relief to sit down and try to get them on the page.

PB: How weird was it that you went from writing about Donald Trump and these snooty society types in a New York magazine gossip column to covering down-and-dirty crime in the Bronx and Queens? Most people who went to the kind of colleges you went to didn’t really understand why you would want to do that. A lot of them might have thought that was deliberately stepping from the penthouse into the gutter. How can you explain that to “normal people”?

PT: Honestly, it was such a step up. I mean, I took that society job because I needed the work but I hated that phony baloney ego stroking. I had a low opinion of journalists who covered rich people, hoping that some of their god-like aura that surrounds the wealthy would rub off on those ink stained schlubs.. It’s sad. Pathetic, really. I wasn’t raised around people who were wealthy and powerful and I guess I never got the memo that I was supposed to measure people for the size of their bank accounts. Covering crime, I learned a lot about people – and saw some pretty terrible things, brutal things, craven things but also situations in which people acted in a way that was amazing, astonishing, heroic and beautiful. Also, funny. It really helped me formulate a world view.

PB: One thing I love about re-reading the nove—I should say one of the things that I love—is that it captures a particular time in the city and the romance of the Big City newspapers in what was probably their last great era. But there were also terrible things going on: rampant inequality, five or six murders a day, AIDS, and all the other hallmarks of the 80s and 90s?, Do you think younger readers will understand what was fun about being a reporter then?

PB: One thing I love about re-reading the nove—I should say one of the things that I love—is that it captures a particular time in the city and the romance of the Big City newspapers in what was probably their last great era. But there were also terrible things going on: rampant inequality, five or six murders a day, AIDS, and all the other hallmarks of the 80s and 90s?, Do you think younger readers will understand what was fun about being a reporter then?

PT: Well, it wasn’t a desk job, that’s for sure, And every day, I felt like I was in it. Anything that was happening in this big wild pulsating chaotic city could randomly come careering into my life. And I never knew on Monday what Tuesday would look like. And it could be wildly frustrating—I mean, standing outside the yellow tape of a crime scene while the detectives talked to my (male) competition—ugh. And it also could be just wild. Like one time, a currency exchange place got robbed at JFK airport and I went out to figure out what had happened. On the face of it, it’s a dumb crime to follow up on. Reporters don’t spend too much time on bank robberies and the like because it’s all corporate PR people trying to prevent you from finding out what happened. But when I got to JFK, the people who worked at the currency exchange place couldn’t wait to talk to me. They were saying “It was Bernie! He robbed us! He’s the sweet old guy who has been sweeping the floors here for 20 years! He did it! But he loved us! He was like family, “What could have come over him?” It was unexpected. They gave me Bernie’s address and I went straight to his house and rang the doorbell. His adult son answered, and he told me this dad was a good man, the centerpiece and caretaker of his big extended family. The son shared that just five minutes ago, the son had found a shoe box of cash and a note, which he produced for me. The note recounts that Bernie, at the insistence of his family, had gone to the doctor for his longtime stomach ache and while he was waiting for the test results, he’d become convinced he was dying of cancer. He admitted, apologetically, that he’d robbed his old friends at the currency exchange place so his family would have some money after he was dead. And that he was going off to kill himself to save him and his family the agony of watching his slow painful death. Well, that’s a story, I thought. But it got crazier. The adult son tells me his dad doesn’t have cancer. The doctor called that morning, after Bernie had left for work, to say Bernie’s stomach pain was caused by an ulcer. Remember, this is before cell phones. So now Bernie is somewhere, believing he’s a wanted man, dying of cancer, getting ready to end his own life. And everyone—his son, his wife, the neighbors, the people he robbed—they all are like “BERNIE COME HOME! IT’S NOT CANCER!”—which of course, was my front page headline the next day. And then the local Tv stations picked it up. And it was the story of the week. I ended up finding Bernie a hot shot lawyer who I knew from another story I was working on, who brokered Bernie’s surrender to the District Attorney, who was totally charmed by the old man’s story. Bernie ended up getting Pepto Bismol and supervised release. I mean, that’s the kind of thing that could happen on a Tuesday. And who knows what Thursday would look like.

PB: I still think the story of Bernie could be a novel as well. But there’s something I notice when you try to tell younger people these stories about the Bad Old Days in the city. They get this kind of petrified look. Sometimes I think they just don’t understand what it used to be like. And then other times, I think they’re just appalled that we were so into the mayhem of it. Especially when we’re trying to explain how things could be terrifying and funny at the same time. What do you think has changed? Could you write a book like Strangers in the Night or The Intruder now?

PT: Some readers are looking for experiences—and stories—that are affirming and comfortable. I don’t think either of us could really relate to that when we were younger (although personally, I get it a little more now.) Generally, we have always put ourselves in weird situations for the sheer joy of hearing people’s stories. I mean, you were in Egypt during the Arab spring, and the West Bank and Gilgo Beach researching that serial killer. I think if you are up for engaging with the true panorama of human experience, the kind of books we’ve written could be for you. PB: When I look at the novel again, I remember how much I loved Kate Murray the reporter. But I also love all the funny little realistic details like the detectives watching the animal documentaries when they’re supposed to be working and the reporter who tries to curry favor by writing “Ode to Sparky,” about a dog who died. Somebody could describe the book as The Front Page meets Sex in the City, but Strangers in the Night is actually much more matter of fact than either of those. What parts stood out for you when you looked at it again?

PT : Awww, Peter. You are too kind. You’ve always been my biggest cheerleader and I appreciate that about you. What stood out for me is the sheer level of energy in these books—and this was before Adderall. And how they are full of longing. I think a lot of people could still relate to that.

***

Peg Tyre, the bestselling author of THE TROUBLE WITH BOYS, has written for Newsweek, the New York Times, the Atlantic, Fast Company and Scientific American. She has won numerous awards, including a Pulitzer Prize, a Clarion Award, and a National Education Writers Association Award and was a finalist for a National Magazine Award. Tyre’s novel, STRANGERS IN THE NIGHT, was recently re-released by Dead Sky Publishing. She lives in New York City with her husband, novelist Peter Blauner, and their two sons.

Peter Blauner is the author of nine novels, including THE INTRUDER, a New York Times bestseller and bestseller overseas that will soon be released for the first time in hardcover from Dead Sky Publishing. He first broke into print as a journalist, writing cover stories for New York magazine about crime and politics. He has written for numerous TV shows, his novels have been published in twenty-five languages and his short fiction has been anthologized in Best American Mystery Stories and NPR’s Selected Shorts from Symphony Space. He lives in Brooklyn, New York with his wife, the bestselling author Peg Tyre.