The thief of perfume is, in fact, one of the most active of the twenty-first century. In the UK, cosmetics/perfume was the fourth most-shoplifted category in 2019 (after packed meat, razor blades, and whisky/champagne/gin). In the US, perfume is first on the list of products pinched by women, and an AdWeek list of the ten most shoplifted items ranks Chanel No. 5 at No. 9 (a few notches down from Axe body spray).

Just ask Mrs. Thyra G. Youngstrom. In a 1959 news article, she’s reported as having discovered her West Hartford, Connecticut, home had been ransacked. It seemed everything was out of place, but nothing was gone: until she noticed she was poorer two bottles of Chanel No. 5. (But she was better off than the victims of a 1971 break-in, who were robbed of 16 bottles of perfume valued at $5 each and nine bottles at $35 each. The thief also ate two pieces of cake.)

Even back in 1937, the comic-strip detective Dick Tracy busted a ring of pretty, sticky-fingered gold-diggers. “Listen, Mintworth,” he tells one of the thieves’ marks, “in case you don’t know it, your fiancée is just a plain ordinary little perfume thief and shoplifter.”

And perfume thieves have tantalized news reporters for over a century—many a headline writer has evoked the metaphors of the police hound, with detectives on the scent, or following their noses, or sniffing around. In some early twentieth-century articles, the theft seems invented by the headline writer just for the pun of it.

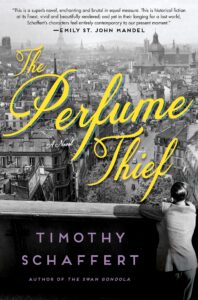

For my novel The Perfume Thief, I devised the title character’s career before I’d had any sense of such a bandit’s inclinations. I concluded that Clementine, my narrator, would need to be flexible in her grift. For her, her specialization is as much an intellectual and emotional exercise as it is a money-making scheme. At the heart of it all is her fascination with perfume.

And such a fascination has motivated perfume thieves in real life too. The spectrum of perfume thievery has ranged from the petty thief who lifts a half-empty bottle off a lady’s vanity to the millions made by corporate counterfeiters. Here are some examples of perfume thieves in action:

- Over the decades, any number of trucks have been highjacked and warehouses robbed of boxes of perfume, the thieves delivering the contraband to stores that would sell the bottles at deep discount, as “bankrupt stock” or “smuggled goods.” A New York Times report from 1927 is like something out of that Dick Tracy strip, with a truck full of “imported perfumes, toilet waters, and coffrets” overtaken by thugs credited with lines like “Get out and no funny business” and “don’t make any noise or it’s curtains for you.” One of the biggest heists took place in Nice, France: concrete containers of jasmine perfume valued at 1.5 million (in 1946 dollars), stolen from a factory.

- When exploring a plundered Egyptian tomb, archeologists discovered that perfume had been among the things not stolen by the tomb raiders. So the archeologists stole it for themselves; or, rather, procured it for historical purposes. The relics were the remnants of the vanity of a woman of the Eleventh Dynasty, which included “little sticks of sweet-scented wood for perfumes, which she made by grinding off the ends and collecting the powder from them to sprinkle in her clothes or hair,” according to an article in the New York Times in 1932.

- An 1896 edition of The National Druggist reported on an apprentice at Pinaud, a famous Parisian perfumer, who broke off on his own and sold his product to the American market—a product that smelled suspiciously like that of his former employer. Though the perfumer was honest on his labels, indicating to his consumers that he’d only worked for Pinaud, he wrote it all in French. Any non-French-speaking American (which was most of them) would only be able to read the word Pinaud, in big letters. And though the perfumer defended himself to the judge by saying that nowhere on the label does it actually say the perfume was made in France, “Paris France” had been blown into the glass of the bottle, the words entirely see-through but in raised lettering.

- A perfume thief breached the security of the Security Council Chamber of the United Nations in 1987, breaking into a display case to make off with two antique, solid-gold bottles filled with a rare Omani perfume, gifts to the UN from the sultanate of Oman.

- In a nifty bit of theft on theft, thirty thousand, one-ounce bottles of forged Chanel No. 5 were seized by New York City police in 1974, not because they were counterfeit, but because they’d been stolen from their rightful owner’s trucks, along with hi-fi and other electronic equipment.

- New York Times columnist Enid Nemy drew a distinction in 1973 between “samplers” (those who compulsively spritz themselves with everything on the department store perfume counter) and the “stealers” whose interest is “in prestige, rather than scent.” Among the stealers she cited were those who somehow absconded with the oversized display bottles promoting Joy by Jean Patou (originally advertised as the most expensive perfume in the world), which were filled only with a honey-colored water. Though entirely without scent, the bottles would look impressive on a vanity top.

And then there are the stealers interested in the scent and the prestige … what follows is my perfume thief Hall of Fame:

S.R. Kinney (1927)

Kinney was brought before “the lunacy commission” in 1927 after stealing a vial of perfume valued at $12.50 from a drug store. Brought before the judge, he admitted to having been arrested many times for “pilfering rare and costly perfumes,” according to the Los Angeles Evening Express. “Kinney declared he had never taken anything other than perfumes, for which he has a passion, and that he was not in a pecuniary position to purchase the costly scents.”

Florence Price (1923)

The 18-year-old Price doused herself in perfume, sashayed among her friends in the neighborhood, and claimed the fragrance was a gift from a foreign admirer. This hubris led to her arrest, and she admitted to police that she’d been on her rooftop at midnight, and the scent of the perfume from the neighboring apartment had lured her to crawl in through the window. According to the New York Times, Price “was amazed at the beautiful clothing and perfume and couldn’t resist the impulse to take them.”

Norman Desjardin (1949)

With perhaps the best name for a perfume thief, Desjardin (French for “gardens”) robbed $3,500 worth of cosmetics from the storeroom of a drugstore where he worked as an electrician. The Windsor (Canada) Star reported that the detectives entered Desjardin’s home, and the scents of Opening Night, Command Performance, and Breathless “were very strong.”

Henry Dienges (1940)

We often have to read between the lines to find stories of queer romance in old newspapers. The Sunbury (Pennsylvania) Daily Item reported that Dienges, “a penniless salesman” lived with one John Tobias for a number of months; the article even notes that Tobias cared for him when he fell ill and was hospitalized. Tobias went so far as to put Dienges into business, by buying perfume for Dienges to peddle door to door. (One headline features coy quotation marks around “best friend” in describing their relationship.) Dienges, ever the cad, left Tobias in the middle of one night, sneaking off with $250 worth of the perfume.

Thomas Jones (1908)

The Journal Times of Racine, Wis., reported that Jones stole a $7 bottle of perfume from a drugstore. “When he came into court the room was soon filled with the delightful odor from his perfume saturated clothing.” It’s hard not to sympathize with Jones.

It makes for a swift and efficient morality tale: the crook steals a bottle of perfume and can’t resist spritzing it on for his court date. Vanity as motivation and downfall.

***